Wyoming Labor Force Trends

June 2022 | Volume 59, No. 6

Click Here for PDF

Return to Table of Contents

Nursing Assistants and Work-Related Injuries

by: Chris McGrath, Senior Statistician

This article provides a look into how work-related injuries affect nursing assistants and their continued employment in health care. Data from the Survey of Occupational Injuries & Illnesses (SOII) were compared with workers’ compensation reports and matched with wage records to determine if an individual remained working in health care or left for another industry after incurring a work-related injury that resulted in time away from work.

Nursing assistants provide or assist with basic care or support under the direction of onsite licensed nursing staff. Their duties may include helping patients bathe or dress, turning or repositioning a patient, or transferring them between beds and wheelchairs.

The Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) system classifies workers into detailed professions according to their occupational definition; nursing assistants are given the SOC Code 31-1131.

Specific requirements for nursing assistants vary by state. In Wyoming, nursing assistants must complete the following:

- Graduate from a board-approved certified nursing assistant training and competency evaluation program.

- Submit a completed application and fee.

- Submit CBS fingerprint cards and fee.

- Successfully pass NATCEP or similar national exam.

All nursing assistants in Wyoming must be certified by the Wyoming State Board of Nursing (Knapp, et al., 2021). A conviction of any act of sexual molestation is one restriction for certification. All applications are reviewed by the State Board of Nursing for any additional restrictions.

As of May 2020, there were 2,810 nursing assistants employed in Wyoming. The median hourly wage was $15.28 while the median annual wage was $31,785 (OEWS, 2020). Nationally, the median hourly wage was $14.82 and the median annual wage was $30,830. Nursing assistants may work full- or part-time and may be required to work weekends, nights, and holidays. The low wages and high risk of injury in this occupation present challenges for nursing assistants (BLS, 2021).

According to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS, 2021), employment in the nursing assistants occupation is projected to grow 8% nationally from 2020 to 2030, about the same as the overall projected growth of 7.8% for all occupations. Approximately 192,800 openings for nursing assistants are projected for each year on average. According to long-term occupational projections from the Research & Planning (R&P) section of the Wyoming Department of Workforce Services, Wyoming is projected to add 440 new nursing assistant jobs from 2018-2028 (Yetter, 2021). In addition to new jobs, Wyoming is projected to have 1,930 openings for nursing assistants due to exits and 2,094 due to transfers.

As the need for nursing assistants continues to grow, the importance of retention and recruitment has become vital. High demands, physical stress, and chronic workforce shortages contribute to a working environment that fosters one of the highest workforce injury rates in the United States.

Nationally, nursing assistants are injured on the job at more than three times the overall rate of all occupations (Faler, 2018). According to Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses (SOII) data, nursing assistants in Wyoming reported 120 nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses involving days away from work in 2019 and 90 in 2018. Comparing those figures to another occupation with high injury rates, construction laborers in Wyoming accounted for 100 nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses involving days away from work in 2018 and 80 in 2019 (SOII, n.d.).

In 2018, the primary sources of injury for nursing assistants were patients and someone other than the injured employee. Sprains, strains, and tears were reported as the physical characteristic of the injury for 50 of the cases, followed by violence and other injuries by persons or animals with 20 cases. The parts of body affected the most in 2018 were trunk and back with 30 cases each. The primary source of injury in 2019 was the same as reported in 2018, while soreness, pain was reported as the physical characteristic of the injury for 50 cases. Sprains, strains, and tears accounted for 40 of the cases. Further, trunk (50) and back (40) were the part of body most affected in nursing assistants in 2019.

Back and neck strains from transferring patients, lifting patients, or helping them dress are common causes of injuries that nursing assistants incur on the job. The health care & social service industry experiences the highest rates of injuries caused by workplace violence, and workers in this industry are five times as likely to suffer a workplace violence injury than workers overall (BLS, 2020). Health care workers accounted for 73% of all nonfatal workplace injuries and illnesses due to violence in 2018. Patients can become aggressive or confused and physically attack nursing assistants.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration classifies significant health hazards in five categories: safety, chemical, biological, physical, and ergonomic. Safety hazards include any type of substance, condition, or object that can injure workers, such as spills on the floor, cords and boxes on walkways, and falls. Chemical hazards occur when there is exposure to vapors, gases, fumes, or other substances. Biological hazards refer to an employee coming in contact with blood, animal feces, or viruses. Physical hazards can occur with or without contact. Examples of this include exposure to radiation, working in extreme heat or cold, or exposed to loud noise. Ergonomic hazards are related to musculoskeletal disorders. These types of hazards occur when there is repetitive work or certain positions strain any part of the body (Grainger, 2021).

Methodology

The Research & Planning (R&P) section of the Wyoming Department of Workforce Services conducts the Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses (SOII) for Wyoming in cooperation with the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics annually as part of a nationwide data collection effort. SOII data are collected in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and Virgin Islands; the estimates from this survey are the primary source of information on nonfatal work-related injuries and illnesses in the United States. The data collected include estimates of incidence rates by industry and the nature of the injury or illness. Worker demographics — such as age, gender, and occupation — also are included. Case characteristics, including part of body, source of injury or illness, the manner in which the injury or illness was produced or inflicted, and the nature or physical characteristics of the disabling injury or illness are covered as well.

R&P utilizes several data sources for its research, some of which were used for this analysis. One of these is the Wyoming Unemployment Insurance Wage Records database, which contains wage information provided quarterly by the state’s employers for all of their employees, as well as other variables such as worker industry and location. Data related to gender and age are identified by linking Wage Records to the driver’s license files from the Wyoming Department of Transportation. R&P has data-sharing agreements with 11 partner states, which include wage record information that provides opportunity to track employment outside of Wyoming.

Another data source used for this analysis was the Wyoming Worker’s Compensation database, which contains injury and illness data reported by all Wyoming businesses required to carry workers’ compensation insurance.

A search using SOII data from 2018 and 2019 found 169 cases of nursing assistants across all industries who had a work-related injury or illness requiring days away from work and/or days of job transfer restriction. The case details from the SOII such as name, employer, job title, birthdate, date of injury, type of injury, and part of body injured were matched to data in the state’s workers’ compensation system. Of the 169 original SOII cases, 160 matched with the state’s workers’ compensation database. Social security numbers were needed to match with unemployment insurance and wage records and since the SOII does not collect social security numbers, this information was gathered from the workers’ compensation system. Social security numbers were then used to match injured nursing assistants to wage records to identify the employer and industry in which they were injured and determine if they went back to work for the same employer, left to work for another employer, or remained working in the health care industry four quarters after injury.

While R&P is able to identify a person’s job in the SOII, wage records do not capture the occupation in which an individual works. Because of this, R&P is able to identify the occupation in which an individual was working when they were injured, but is not able to track the occupation using wage records. The North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes were used to identify which industry the employee worked in a year after the injury.

Analysis

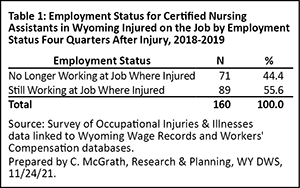

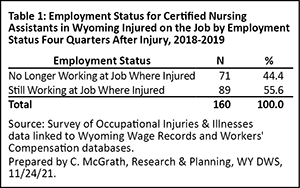

Of the 160 individuals who were matched with workers’ compensation, 71 (44.7%) were no longer working for the employer where they were injured, while more than half (89, or 55.6%) were still working for the same employer four quarters after date of injury (see Table 1).

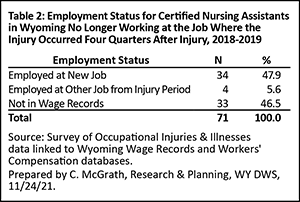

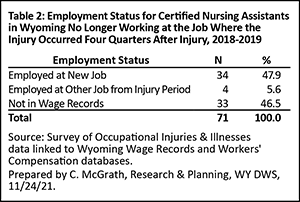

Four quarters after injury, 33 of the 71 individuals who were no longer working for the employer were not found in Wyoming wage records or a partner state, so R&P was unable to track their employment (see Table 2). An additional 34 (47.9%) were found working for an employer other than the one they were working for when injured. Finally, the remaining four (5.6%) were working for two employers at the time of injury, and were still working for the other employer four quarters after injury.

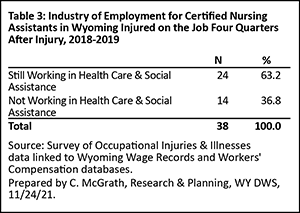

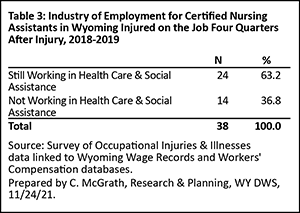

Table 3 shows there were 63.2% of the 38 still working in health care & social assistance one year after being injured compared to 36.8% who left the health care industry entirely. While this difference seems minimal, it does demonstrate individuals working in health care are more likely to stay working in health care in some capacity.

Conclusion

While injury rates for nursing assistants are high, data show a large percentage of nursing assistants who were injured on the job remained working in health care after the injury occurred. The data also revealed over half of the individuals no longer found working for the employer where they were injured left health care to work in a different industry. As the need for nursing assistants in Wyoming and nationally continues to grow, retention in this occupation will be vital. Ensuring there is proper safety equipment and training to reduce injuries could be key to increasing the percentage of nursing assistants who remain employed in health care.

References

Faler, K. (2018, June). Nursing Assistants in Wyoming Round 2. Research & Planning, WY DWS. Retrieved October 3, 2021, from https://tinyurl.com/bdhh8mna

Grainger Know-How. (2021). OSHA’s 5 workplace hazards. Retrieved October 13, 2021, from https://tinyurl.com/bdcb59sp

Knapp, L., Glover, T., and Moore, M. (2021, June). Directory of Licensed Occupations in Wyoming. Research & Planning, WY DWS. Retrieved May 23, 2022, from https://tinyurl.com/4ekfem59

Occupational Employment and Wages Statistics. (2020). Retrieved using the LEWIS program.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2021). Nursing assistants and orderlies. Occupational Outlook Handbook. U.S. Department of Labor. Retrieved October 11, 2021, from https://tinyurl.com/3ptx2vf9

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2020). Workplace violence in healthcare, 2018. Retrieved November 17, 2021, from https://tinyurl.com/y4ztkkya

Yetter, L. (2021, June). Wyoming long-term sub-state occupational employment projections, 2018-2028. Research & Planning, WY DWS. Retrieved October 11, 2021, from https://tinyurl.com/2p9f2sy3

.svg)

Wyoming at Work

Wyoming at Work