Demographics and Earnings of Persons Working in Wyoming

by County, Industry, Age, & Gender, 2000-2018

Table of Contents | Introduction | Definitions | Articles | Home

Tables by Industry, County, Age, & Gender, 2000-2018 (Excel)

Published October 2019.

Changes in Wyoming’s Workforce Demographics: 2014-2018

by: Michael Moore, Editor

See tables and figures for this article.

Originally published in the August 2019 issue of Wyoming Labor Force Trends.

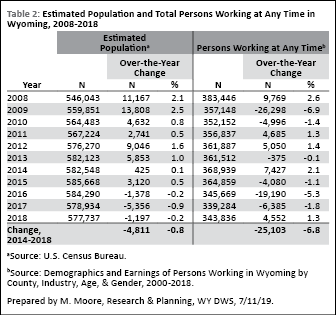

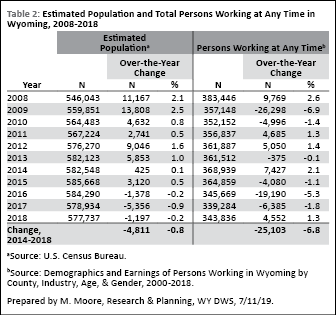

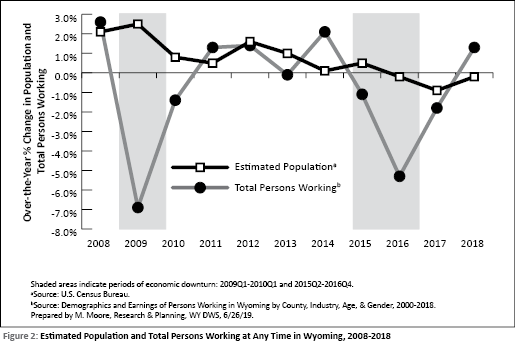

From 2014 to 2018, the total number of persons working in Wyoming at any time decreased by 6.8%, or more than 25,000 workers. During that same period, Wyoming’s population declined by an estimated 0.8%, or just under 5,000 individuals.

The number of persons working in Wyoming at any given time is influenced by a variety of factors, such as economic conditions, population changes, and demographic trends. This article provides a look at how the demographics of Wyoming’s workforce have changed over the last two decades, particularly from 2014 to 2018.

The related article on page 8 of the August 2019 issue of Wyoming Labor Force Trends includes the methodology and definitions for research presented in this article. Complete demographics tables from each calendar year from 2000 to 2018 are available from the Research & Planning (R&P) section of the Wyoming Department of Workforce Services online at https://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/earnings_tables.htm.

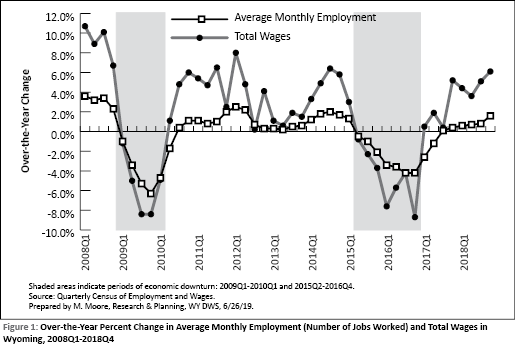

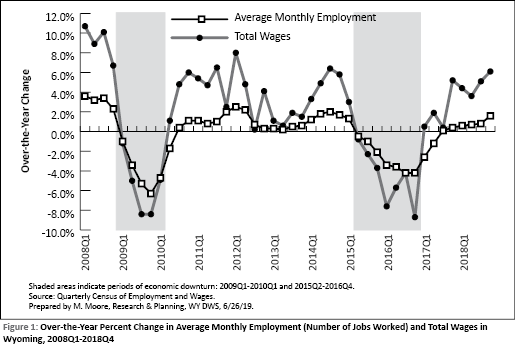

Effects of Economic Downturns

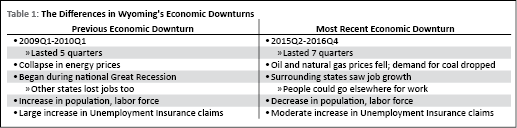

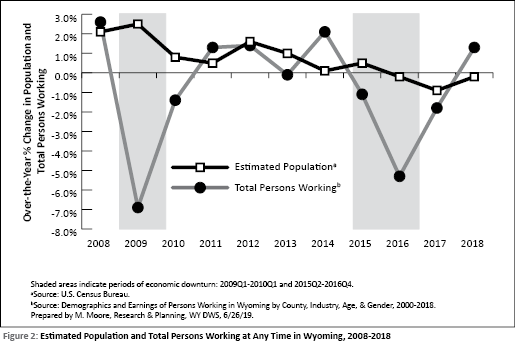

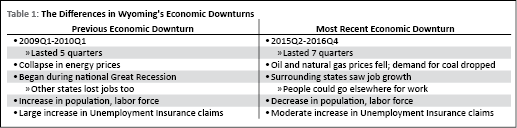

Wyoming’s population and workforce are shaped by the health of the state’s economy. Over the last 10 years, Wyoming has been faced with two prolonged economic downturns. R&P has defined economic downturn as a period of at least two consecutive quarters of over-the-year decline in average monthly employment (the number of jobs worked) and total wages, based on data from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW). The previous economic downturn lasted five quarters from 2009Q1 to 2010Q1, while the most recent economic downturn lasted seven quarters from 2015Q2 to 2016Q4 (see Figure 1).

Both economic downturns were preceded by declining energy prices (see Table 1). The previous economic downturn lasted five quarters from 2009Q1 to 2010Q1, was preceded by an extended period of rapid economic growth, and began during the national Great Recession, which started in December 2007 and lasted through June 2009 (NBER, 2010). The most recent economic downturn resulted from a substantial decline in the demand for and cost of natural resources such as coal, oil, and natural gas (Gallagher, 2016), but occurred during a time of growth for many surrounding states.

Table 2 and Figure 2 show how Wyoming’s population and the total number of persons working were affected by the two economic downturns. During the previous economic downturn, the state’s population continued to grow even as the number of persons working decreased. This suggests that some Wyoming residents who lost their jobs stayed in the state, since surrounding states also lost jobs during the national Great Recession.

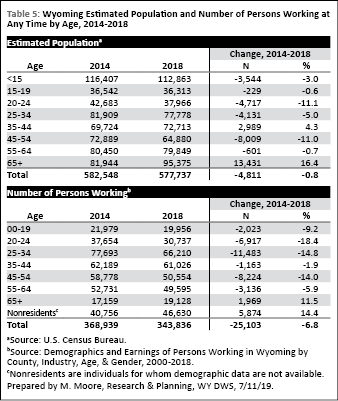

Wyoming’s estimated resident population in 2018 was 577,737, a decrease of 4,811 people (-0.4%) from the estimated 582,548 in 2014, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau (2019). Prior to 2015, Wyoming’s population increased each year, including during the previous economic downturn from 2009Q1 to 2010Q1 when the number of persons working decreased. In contrast, during the most recent economic downturn, the estimated population and number of persons working both decreased, suggesting that some Wyoming residents who lost jobs in 2015 and 2016 apparently left the state.

The growing economies of neighboring states may have contributed to Wyoming’s declining population since the start of the most recent economic downturn. In 2018, the average rate of job growth from prior-year levels for Wyoming was 0.6%, substantially lower than states such as Utah (3.4%), Idaho (3.3%), and Colorado (2.5%), as noted by Moore (2019). Wyoming residents who lost jobs during the most recent economic downturn may have been able to quickly find work in another state.

Figure 2 shows the impact that the two recent economic downturns had on the total number of persons working in Wyoming. The total number of persons working decreased by 26,298 individuals (6.9%) from 2008-2009, and then by 19,190 individuals (5.3%) from 2015-2016. In 2018 there were 343,836 persons working in Wyoming at any time, up 1.3% from 2017 but still lower than any other year in the last decade.

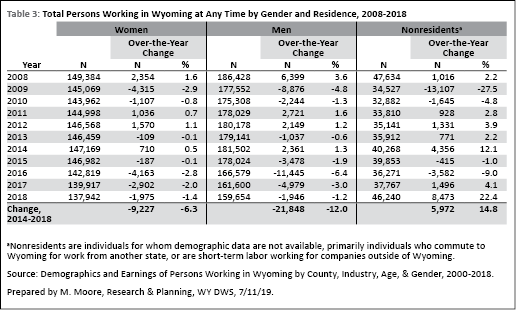

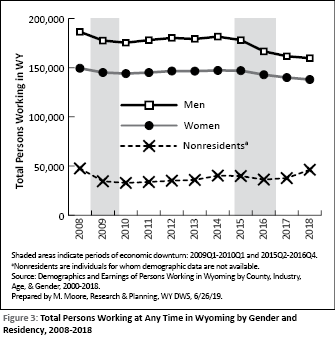

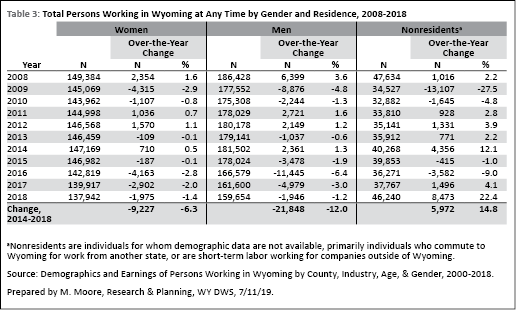

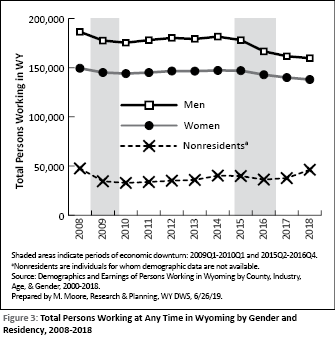

Changes by Gender and Residency

As illustrated in Table 3 and Figure 3, the numbers of men and women working in Wyoming at any time declined during each of the last four years. From 2014 to 2018, the number of women working in Wyoming declined by 6.3%, while the number of men dropped by 12.0%. In comparison, the number of nonresidents working in Wyoming increased by 14.8% from 2014 to 2018. In 2018, there were more nonresidents working in Wyoming than any other year since 2008.

During times of economic expansion, Wyoming employers have historically imported labor from other states after exhausting the local labor supply. This may have been the case in the quarters following the recent economic downturn. Figure 1 shows that Wyoming has experienced moderate job growth since the end of the most recent economic downturn. From 2017Q3 to 2018Q4, the average rate of job growth was 0.7%. But because so many workers left the state during the recent economic downturn, employers may have had a smaller pool of resident workers from which to hire as the state added jobs while recovering from the downturn. Once employers exhausted the resident labor supply in 2017 and 2018, they may have turned to out-of-state workers to fill job openings.

Changes by Age and Generation

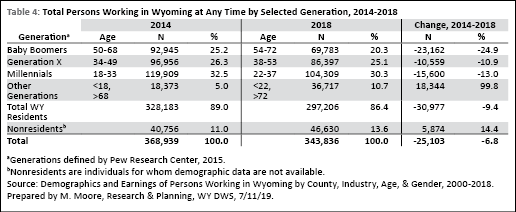

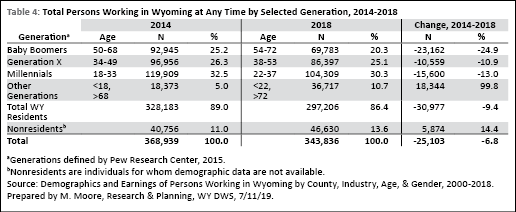

In 2014 and 2018, Wyoming’s workforce consisted primarily of individuals from three generations: the Baby Boom Generation, Generation X, and the Millennial Generation, as defined by the Pew Research Center (2015).

The Baby Boom Generation refers to the approximately 76 million individuals born in the U.S. between 1946 and 1964. In 2014, Baby Boomers were between the ages of 50-68 and made up 25.2% of all persons working in Wyoming (see Table 4). In 2018, Baby Boomers were ages 54-72 and made up 20.3% of the workforce. From 2014-2018, the number of Baby Boomers working in Wyoming at any time decreased by 24.9%.

Generation X refers to approximately 55 million individuals born from 1965 to 1980. In 2014, Generation Xers were ages 34-49 and accounted for 26.3% of total persons working in Wyoming. In 2018, Generation Xers were ages 38-53 and made up 25.1% of those working at any time. The number of Generation Xers working in Wyoming at any time decreased by 10.9% from 2014-2018.

The Millennial Generation refers to 66 million individuals born from 1981-1996. Millennials were ages 18-33 in 2014 and made up 32.5% of the total number of persons working in Wyoming. In 2018, Millennials were ages 22-37 and accounted for 30.3% of all persons working at any time. The number of millennials working in Wyoming decreased by 13.0% from 2014-2018.

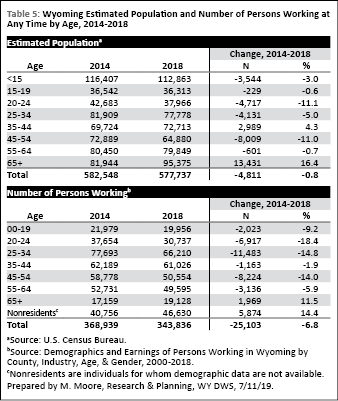

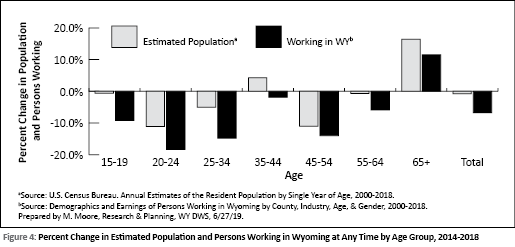

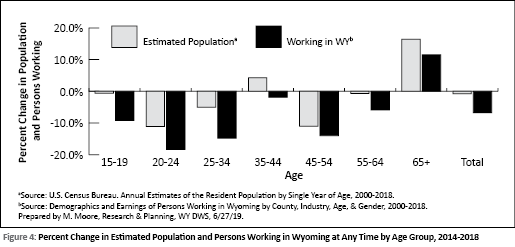

Table 5 shows the estimated population and number working by age group in 2014 and 2018. Figure 4 was created using the data from Table 5, and shows a substantial decrease in the estimated population and number working for individuals younger than 35. For example, the population of individuals ages 20-24 decreased by 11.1% (4,717 persons), while the number working decreased by 18.4% (6,917 persons). Altogether, the estimated population of individuals between the ages of 15 and 34 decreased by 5.6% (9,077 persons) and the number working decreased by 14.1% (20,107). Of the 25,103 fewer persons working in Wyoming from 2014 to 2018, the vast majority (20,107, or 80.1%) were under age 35.

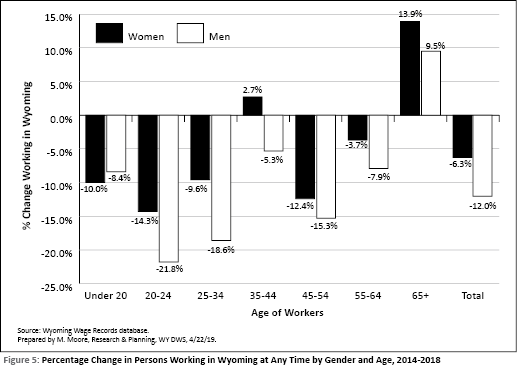

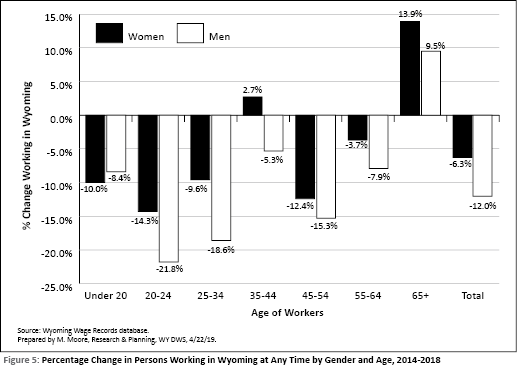

Harris (2013) and Moore (2017) both demonstrated that younger male workers are the most likely to lose their jobs during times of economic downturn in Wyoming. As indicated by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2016), during economic downturns, employers tend to retain older, more experienced workers and let go of younger, less experienced workers. This can be seen in Figure 5, which shows that the greatest decreases in persons working from 2014 to 2018 were seen in men ages 20-24 (-21.8%) and ages 25-34 (-18.6%).

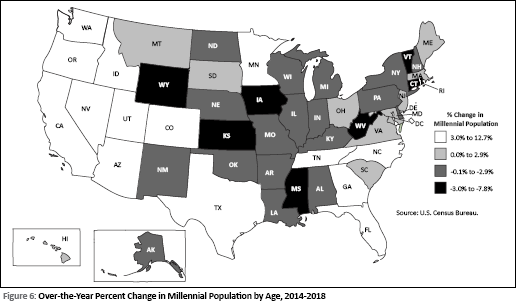

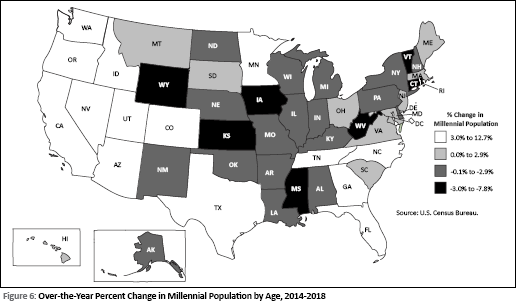

The decrease in younger workers is also due in part to millennials leaving Wyoming. Several studies have discussed millennials exiting rural areas for states with large metropolitan areas. Cromartie (2017), for example, noted that about 68% of rural counties lost population between 2010 and 2016, and Kumar (2018) stated that, “rural areas lack academic and economic opportunity compared to metropolises.”

Wyoming’s millennial population decreased from 130,897 in 2014 to 124,275 in 2018 (-6,622, or -5.1%; see Figure 6). The 5.1% decrease in Wyoming’s millennial population was the third largest in the nation, behind Vermont (-7.8%) and Rhode Island (-5.7%). In contrast, surrounding states with large metropolitan areas showed noticeable growth in their millennial populations, including Colorado (11.9%) and Utah (5.5%).

These data support the idea that Wyoming’s younger workers are leaving to find work in nearby states with metropolitan areas. Liu (2019) observed, “Movers tend to be much younger than non-movers, and this is particularly true for Wyoming,” and “if millennials continue to move to big metro areas, the state may face a serious labor force shortage and faster population aging in the near future.”

The decline in the 45-54 age group is largely a function of the way generations have been defined. In 2014, baby boomers were ages 50-68, and made up more than half of the 45-54 age group. By 2018, baby boomers were ages 54-72 and had mostly moved out of the 45-54 age group and into the 55 or older group. As the baby boomers aged out, there were fewer gen Xers moving into the 45-54 age group.

Conclusion

The total number of persons working in Wyoming at any time increased from 2017 to 2018, but remained considerably lower than pre-economic downturn levels from 2014. The number of resident women and men working in Wyoming declined for the third straight year, so the overall increase in persons working was driven by more nonresidents working in Wyoming than at any time since 2000, with the exception of 2007 and 2008. In addition, the decline in workers younger than 35 lead to a new 18-year low for Wyoming as the number and proportion of young workers in Wyoming’s labor market continued to decline. Also, the number of older workers increased, as more baby boomers continued to work past age 65.

References

Bullard, D. (2015, January). Local jobs and payroll in Wyoming in second quarter 2014: Construction leads job growth. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 52(1). Research & Planning, Wyoming Department of Workforce Services. Retrieved April 24, 2019, from https://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/trends/0115/qcew.htm

Cromartie, J. (2015, September 7). Rural areas show overall population decline and shifting regional patterns of population change. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://tinyurl.com/yxdw5e5k

Gallagher, T. (2016, April). Chapter 1: Economic analysis. Workforce Planning Report 2016, Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 53(4). Retrieved July 11, 2019, from https://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/trends/0416/a1.htm

Harris, P. (2013, May). Demographics of UI claimants: More males continue to receive benefits than females. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 50(5). Research & Planning, Wyoming DWS. Retrieved March 19, 2019, from https://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/trends/0513/a2.htm

Kumar, D. (2018, March 23). Rural America is losing young people - consequences and solutions. Wharton Public Policy Initiative, University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://tinyurl.com/yyhapu6w

Liu, W. (2019, June 20). Wyoming’s population continued to age fast from July 2017 to July 2018. Wyoming Economic Analysis Division. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://tinyurl.com/yx975frq

Moore, M. (2017, August). Wage records in Wyoming, 2000-2016: Males, younger workers were the most affected by the recent economic downturn. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 54(8). Research & Planning, Wyoming DWS. Retrieved March 19, 2019, from https://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/trends/0817/0817.pdf

Moore, M. (2019, July). Chapter 2: Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages: Construction sector adds jobs for the first time in 3 years. 2019 Wyoming Workforce Annual Report. Retrieved July 11, 2019, from https://tinyurl.com/y4emg35p

National Bureau of Economic Research. (2010, September 20). U.S. business cycle expansions and contractions. Retrieved July 21, 2017, from http://www.nber.org/cycles.html

Pew Research Center. (2015, September 3). The whys and hows of generations research. Retrieved June 28, 2019, from https://tinyurl.com/y6lpwoev

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. (2014, June 17). SA04 State income and employment summary. Retrieved March 19, 2019, from https://tinyurl.com/n32avt6

U.S. Census Bureau. (2019, June). Annual estimates of the resident population by single year of age and sex for the United States, States, and Puerto Rico commonwealth: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2018. Retrieved July 11, 2019, from https://factfinder.census.gov

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2016, March 24). Multifactor productivity. Changes in composition of labor for BLS multifactor productivity measures, 2014. Retrieved March 19, 2019, from https://www.bls.gov/mfp/mprlabor.pdf

.svg)

Wyoming at Work

Wyoming at Work