The Recent Labor Market Downturn as a Natural Experiment, Part 3:

Previous Unemployment Insurance (UI) Spells as a Predictor of the Length of Future UI Benefit Collection

According to Heckman and Borjas (1980), employment and unemployment may depend on three different types of state dependence. In this article we focus on occurrence dependence which rests on the assumption that the number of previous spells of unemployment determines the probability of future employment. This article contributes to the state dependence literature by including the economic conditions before and after the first use of the Unemployment Insurance (UI) system. Using UI claims data, we found that economic conditions before and after the first spell of unemployment played a significant role in determining length of future UI benefit collection. We found little evidence that a claimant’s personal characteristics contribute to the length of future UI benefit collection. Implications for workforce service agencies are also discussed.

This is the third article in a three-part series. Part 1 can be found in the November issue of Wyoming Labor Force Trends. Part 2 can be found in the December issue of Trends.

If state workforce agencies set a goal of decreasing the number of benefit weeks claimed, past benefit collections have been found to play a significant role in leaving the UI system which can impact this goal (Corak, 1993; Niedergesäss, 2012). Due to the variability in the use of UI prior, during, and after the recent economic downturn, many authors deem it a natural experiment (Kahn, 2011; Rothstein, 2011). A natural experiment is one way to evaluate large-scale policy changes and their effects on labor market activity (van Ours & Vodopivec, 2006). A natural experiment is one where clusters of individuals are exposed to treatment or control conditions that are determined by nature or laws and not induced by the researcher. If the variation in subsequent claim duration is accounted for by personal characteristics at the time of the first UI claim, then policies should target those specific characteristics to reduce future claim duration. However, if the variation is due to macro- and micro-economic conditions, such policies will be ineffective in reducing the number of weeks of UI benefits claimed.

Parts I and II of this series explored the rate of UI claimants leaving Wyoming’s labor market after UI benefit collection and the characteristics of those claimants who will become repeat claimants. In the first two articles in this series, we found the behavior of UI claimants differs based on labor market histories and regional and local economic conditions.

In this article, we include employment history and economic condition data before and after the first spell of UI to simulate the various experiences of collecting UI. We found that variation in the number of weeks of successive UI spells was accounted for more by macro- and micro-economic conditions than by claimant characteristics. This result suggests that implementing or changing policies that target claimant characteristics is likely to be ineffective in reducing the number of weeks of benefit collection in successive claims. Further, we found that claimants who do not return to work for the same employer and make higher wages after collecting UI benefits claim fewer benefit weeks in subsequent claims than those who do return to the same employer. This result suggests that there may be an incentive to learn the UI system for those claimants who anticipate repeat use of the UI system.

We also found that the number of weeks of benefits claimed in successive UI spells changes depending upon the level of wage gain (or loss) surrounding the first claim and the weekly UI benefit amount they receive. Claimants who experience a loss in wages after collecting benefits and receive small UI benefit payments claimed more weeks of UI benefits in subsequent claims. This result may be due to claimants searching for more suitable work reducing the likelihood of using the UI system again.

R&P research on UI claims can be found here: http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/ui.htm.

Overview

In this article, we examine the number of weeks of UI benefits collected using the theoretical framework of state dependence developed by Heckman and Borjas (1980). State dependence is the concept that past labor market states (employment and unemployment) have a causal impact on future labor market states. According to Heckman and Borjas, there are three types of state dependence: duration dependence, occurrence dependence, and lagged duration dependence. Duration dependence is the length of the current spell of unemployment that determines the likelihood an individual will remain unemployed. Occurrence dependence refers to the number of previous spells of unemployment that determines the probability of becoming or remaining unemployed. Lagged duration dependence refers to the probability of remaining on unemployment insurance depending upon the length of previous spells of unemployment.

Many studies have focused on the effect of state dependence in the context of transitioning from one employment state to another such as from employment to unemployment and vice versa (Arranz & Muro, 2000; Cappellari, Dorsett, & Haile, 2010; Doiron & Gørgens, 2008; Heckman & Borjas, 1980; Niedergesäss, 2012; Omori, 1997; Ruhm, 1991). The results of these studies are mixed as to whether the effect of true state dependence has an impact on future labor market states (including in cross-cultural settings). Even though state dependence refers specifically to employment transitions as the outcome, Corak (1993) applied the theoretical underpinnings of occurrence dependence to the length of future UI benefit collection. Using data from the Canadian UI system, Corak found that occurrence dependence played a role in the length of successive UI spells by way of a “scarring” effect of unemployment. The scarring effect is thought to involve changes in tastes and human capital decay as a result of being employed in a sector of the labor market where unemployment is a regular experience (e.g., construction). Examining the effects of unemployment “scarring” effects on life satisfaction, Knabe and Rätzel (2011) found that individuals are not only scarred by their experience of unemployment (i.e., unemployment having severe direct negative consequences on future employment opportunities), but this scarring is more a result of the individual’s negative perception of their future labor market participation (the authors refer to this as “scarring”).

Separating true state dependence from unmeasured variables that give rise to unobserved heterogeneity (differing characteristics) among claimants and economic conditions has been recognized. Unobserved heterogeneity is the characteristics (such as work ethic and cognitive ability) that are related to both the predictor variable(s) and the outcome variable. The hypothesis that simply interacting with the UI system (and even unemployment itself) increases lengths of future UI benefit collections rests on two assumptions. First, interacting with the UI system erodes a stigma that collecting UI benefits makes claimants “losers”, and they become more knowledgeable about how the UI system works (Corak, 1993; Gray & McDonald, 2012). Second, UI spells cannot be considered stable across time as both claimant and economic characteristics change from one spell to the next. If a researcher does not properly control for variable changes across spells, the correlation between past experiences and future experiences may be “due solely to uncontrolled heterogeneity” (Heckman & Borjas, 1980). However, Heckman and Borjas note that occurrence dependence is the least restrictive (of the three state dependence types) in terms of necessary assumptions in the presence of unobserved heterogeneity while duration dependence is the most restrictive.

Past Research Limitations

The data in Corak (1993) spanned a long horizon; however, the author noted several limitations. The dataset did not contain information on the labor market behavior of claimants between spells of UI claims. This drawback is significant as claimants’ wage, employment, residency, and industry can change after UI benefit collection and are likely to influence the length of subsequent claims. Due to the amount of weekly benefits received and the length of benefit collection being tied to past earnings, the labor market activity upon re-employment has an impact on the number of weeks a claimant can claim a benefit. Second, Corak did not have access to information on the time spent before the first UI claim or after the end of the last claim. As with the time spent between claims, the variability between claimants on wage and employment histories at these two time periods will likely contribute to future UI benefit collection.

This article builds upon Corak (1993) by including individual labor market history before, between, and after each UI claim. We argue that it is not merely state dependence that leads to an increase in subsequent UI benefit collection, but the various experiences of past UI collection determining the effect on future UI use. Very few studies include data on labor market participation before and after collecting UI benefits limiting the ability of researchers to analyze the effect of economic characteristics surrounding past states of unemployment on future labor market outcomes. The use of individual and economic characteristics only at the start of UI benefit collection restricts our understanding of the relationship between the entire experience of UI interaction (e.g., job search requirements and workforce agency service delivery) and future labor market outcomes. We apply the theoretical concept of occurrence dependence on the experience of collecting UI benefits.

Explaining an individual’s future labor market behavior after an initial state of unemployment has primarily revolved around three main theories. First, the unemployed individual and employer perceived stigma regarding the UI system has been found to increase the probability of remaining unemployed and increase the length of current and future unemployment (Omori, 1997). The level of stigma experienced has been shown to be negatively related to the local unemployment rate with higher levels of unemployment being associated with lower levels of stigma and perceived human capital decay. Second, as individuals interact with the unemployment system (UI), they begin to understand how the system works and due to the generosity of the program adjust employment patterns to maximize the benefits (Gray & McDonald, 2012). Third, higher wages earned prior to unemployment and lower weekly UI benefits paid have been shown to increase the probability of exiting unemployment due to the lower value of being unemployed (Meyer, 1990).

This article attempts to add to the literature by utilizing the statistical method outlined by Heckman and Borjas (1980) to test the effects of the three theories outlined above on subsequent lengths of UI benefit collection. As stated previously, most studies on state dependence and labor market behavior include only demographic and economic characteristics at the time of the claim while not including fluctuations in conditions before and after the claim. Economic conditions before and after collecting UI benefits are likely to affect availability of jobs, work search intensity, and the length of benefit collection (along with unemployment duration) in terms of future UI duration. In the section below, we argue three hypothesized moderating relationships among the characteristics surrounding the first claim on the duration of subsequent UI benefit collection. A moderation variable is one that interacts with the relationship of other variables such that the relationship depends upon the level of the moderating variable.

Stigma Effects and

Unemployment Duration

If a stigma erodes with the first interaction with the UI system, the expected duration of future UI benefit collection should increase. However, as past research indicates during times of high unemployment, employers (and individuals) may be less likely to view collecting UI benefits as stigmatizing (Omori, 1997). The probability of receiving a job offer has been found to decrease during a recession which also decreases the likelihood of re-employment (Kahn, 2011). Jobs during a recession may be part-time or temporary which the worker is likely to be laid off and because the claimant has already interacted with the UI system, the stigma of being a “loser” is likely to have diminished. We argue that the local unemployment rate immediately before collecting UI benefits will moderate the relationship between length of unemployment and longer durations of future use of UI. That is, as the number of unemployed individuals in a labor market increases before an individual begins collecting benefits, the longer an individual will remain unemployed increasing the number of weeks of future UI benefits (a reduced stigma due to the first unemployment spell occurring during times when many individuals are unemployed).

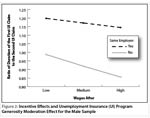

Incentive Effects and

UI Program Generosity

If the generosity of the UI system creates an incentive effect to claim an increased number of weeks in subsequent claims, individuals who are re-employed with the same employer have a greater stake in learning the UI system and learning more about how the system functions compared to those individuals who do not intend to return to their previous employer. Claimants who return to their previous employer may be more likely to use the UI system repeatedly. As part of his social learning theory, Bandura (1986) argues that knowledge is frequently passed from one individual to another and if the individual modeling the behavior is rewarded, then vicarious reinforcement in the observer is likely to increase. From this, we argue that individuals (observers) working in jobs where workers are more likely to be laid off and return to the same employer (e.g., such as in the construction industry), are vicariously reinforced when others (models) are seen benefitting from the UI system, making the observers more inclined to use the experience of the first claim to modify their behavior in subsequent claims.

Reservation Wage and

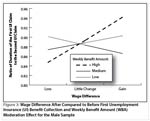

UI Weekly Benefit Amount

An increase in the weekly benefit amount and the number of weeks of UI benefits for which claimants are eligible has been shown to decrease job search intensity, increase the value of being unemployed, and increase a claimant’s reservation wage while claiming benefits (Fishe, 1981). Reservation wage is defined as the minimum wage a worker will accept for any one job offer. Further, higher wages prior to UI benefit collection have been associated with shorter lengths of unemployment due to an increased cost of being unemployed (Meyer, 1990). The UI benefit amount paid during the first claim is likely to be salient to the claimant and those who received low (high) benefits in the past may anticipate low (high) benefits in the future, thus changing the incentive to collect UI benefits depending on the perceived generosity of the UI system. If claimants find employment that pays a higher wage after collecting UI (compared to just prior) and the salience of the UI system is negative (received low weekly benefits), they may perceive the UI system as unhelpful and there is an increased incentive to find employment quickly in subsequent UI spells. We expect that an increase in wages the year after (compared to prior) receiving the first UI benefit will decrease the duration of subsequent UI benefit collection for those individuals who are paid a lower weekly benefit amount.

Methodology

The data used in this article were collected for claimants who received their first UI benefit between first quarter of 2005 (2005Q1) and first quarter of 2013 (2013Q1) in Wyoming. Corak (1993) suggests that claimant behavior is more likely to change between the first and the second interaction with the UI system with only minimal change in subsequent claims. We collected the same data for the second claim to create the UI experience before, during, between, and after the two claims. The second claim could have been filed between 2006Q1 and 2014Q1. Claimants had to collect at least one week of UI benefits on both claims to be included in the analysis. In an attempt to limit the sample to first time UI claimants, all individuals who received Wyoming UI benefits prior to 2005 were excluded from the analyses. However, controlling for prior use of UI in another state is not possible with current Research & Planning (R&P) datasets.

R&P maintains a UI wage records database which includes quarterly wages for approximately 92% of Wyoming workers since 1992. Quarterly wage data, number of employers, and the number of tenured quarters with the same employer(s) were gathered to compile labor market participation four quarters prior and four quarters after each claim was filed. The same labor market information was gathered for the time spent between claims. The number of unique quarters the claimant appeared in wage records was calculated to get a complete history of participation in Wyoming’s labor market. Wage records are submitted by employers who are required to report quarterly wages for UI tax purposes on all employees. Wage and weekly benefit amount data were adjusted for inflation to the 2013 Consumer Price Index (Manning, 2012). The inflation adjustment methodology is available at http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/trends/0812/toc.htm). To measure labor market conditions surrounding the claim, we used local unemployment rates three months prior and three months after each claim. The local unemployment rate allows us to control for economic conditions leading up to the claim and during and after (which is the time period the claimant is searching for work).

Generally, once an individual applies for benefits and receives their first benefit, they have one year to collect the remainder of their benefits (a benefit year). The number of benefit weeks claimed was calculated by counting benefit payments collected between the start of UI benefits (first pay) and the final payment. However, if an individual was eligible for and began collecting extended UI benefits during and after the economic downturn, the weeks claimed continued even after the final payment. During the recent economic downturn and recovery (2009Q1 to 2013Q4), the Federal Government passed legislation allowing for extended UI benefits (up to 13 weeks) for those who continued to be unemployed after the initial benefits were exhausted. The number of continued weeks claimed between final payment and the start of a new claim was calculated to obtain the number of extended benefit weeks. The ratio of the total number of weeks claimed during the second claim and the number of weeks claimed during the first week was calculated using a log-linear function as claim length can never be zero. Moderation variables in multiple regression are multiplied with the independent variables of interest and entered into the model as multiplicative (interaction) variables. Each of the variables that constitute the interaction term must be included in the model to reduce bias in the estimates (Brambor, Clark, & Golder, 2005).

|

According to Heckman and Borjas (1980), a test for the presence of occurrence dependence is a test of the model variables that do not change across spells (spell in-variant) having statistically significant regression coefficients. In the regression model, the change variables control for unobserved heterogeneity (of both claimant characteristics and economic conditions) between claims. See Table 1 for a list and the definition for the variables included in the model.

Results

|

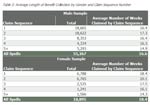

Table 2 shows the relative lengths of benefit weeks claimed by gender and successive claim number. The average length of benefit collection increased from the first to the second spell for both genders; however, the length began to decrease for both genders beginning with the third claim. The total number of male claimants decreased by 10,269 (-55.1%) after the second claim while the total number of females decreased by 4,230 (-62.5%). A total of 24,570 unique claimants were included in the regression model.

|

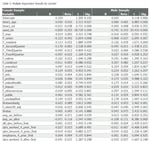

Table 3 shows the results of the multiple regression model by gender with the log-linear ratio of the length of second claim over the first as the dependent variable. The predictor variables that are statistically significant (p < .05) are bolded. For the female sample, several spell in-variant predictor variables are significant indicating that occurrence dependence may be present. However, we would expect that the intercept term would be statistically significant if true occurrence dependence was present. The coefficient on age (.03) indicates that during the first UI spell, older claimants experience an increase in the number of weeks claimed in successive UI claims. Further, individuals with more education collected fewer weeks of UI benefits in subsequent claims. For males, education was not statistically significant. It should be noted that few claimant personal characteristics during the first claim were statistically significant indicating that focusing on specific claimant characteristics to reduce future length of benefit collection may not result in an actual reduction. Many of the variables that were significant pertained to economic conditions (e.g., unemployment rate, quarter of claim).

For both genders, the average unemployment rate three months after the start of benefit collection was significant. If claimants experienced higher levels of unemployment during their first three months of UI collection, the number of weeks they collect UI benefits decreases in subsequent claims. This result supports (Omori, 1997) in that claimants may be less “scarred” by UI benefit collection if unemployment is high during their first use of the UI benefit system due to reduced employer stigma. For males, a claimant who was re-employed with the same employer saw an increase in subsequent benefit collection indicating claimants might be learning the UI system if they are employed in an industry that frequently lays-off their workforce.

|

|

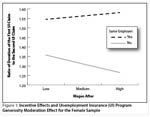

In terms of our three hypothesized moderating relationships, one was statistically significant for females and two for males. For both genders, a claimant going back to work for the same employer moderated the relationship between wages after the first claim and subsequent claim duration (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). Those claimants who earned higher wages after the first claim and did not return to the same employer claimed fewer weeks in successive UI spells compared to those who did return to the same employer. This result supports our hypothesis that for claimants not returning to work with the same employer, learning models may not be as readily available to reinforce the use of the UI system. When others (models) are seen benefitting from the UI system, observers are more inclined to use the experience of the first claim to modify their behavior in subsequent claims.

|

For males, weekly benefit amount moderated the relationship between the wage difference surrounding the first claim and subsequent claim duration (see Figure 3). As expected, claimants who gained wages after receiving UI benefits and received low benefit payments claimed fewer weeks of UI in subsequent claims compared to claimants receiving high benefit payments. The positive slope for claimants receiving high benefit payments is of note. As described in the introduction, the perception of the UI system depending on the amount of benefit payments is likely to be salient the second time a claimant receives UI benefits. For those claimants receiving high benefit payments during their first claim may view the UI system as positive and helpful and claimants may spend more time looking for a job that pays more than their reservation wage thus increasing the wage earned after claiming compared to before their claim.

Of further note, there is a point where the slopes intersect (in the little change in wage category). When claimants experience a loss in wages, those with low benefit payments have higher subsequent UI weeks compared to those with high benefit payments. However, as claimants gain wages, the relationship intersects and those with higher benefit payments claim more weeks of UI. This result suggests that wage change surrounding the first claim plays a significant role in the weeks of benefits claimed in the future depending upon the amount of benefit payment. For instance, claimants who experience low benefit payments (compared to those with higher payments) and a loss in wages after benefit collection may spend more time looking for work during the second claim to avoid the need to continue to claim in the future. This may be due to their perception that the UI system is not as valuable as being employed because of low benefit payments.

For both genders, the unemployment rate prior to receiving the first claim did not significantly moderate the relationship between length of unemployment and subsequent benefit weeks claimed. Further, for females, weekly benefit amount did not significantly moderate the relationship between wage difference and subsequent benefit weeks claimed. It should be noted that the simple slopes in each of the moderation terms were not significantly different from zero. This means we cannot draw conclusions regarding the strength of the slopes of the moderation variables.

Conclusion

This article explored the experience of using the UI system and expanded upon past research by including both personal and economic variables surrounding the collection of UI. We tested for the presence of occurrence dependence with mixed results. We found that several spell in-variant variables (at the time of the first claim) were statistically significant. However, the constant term was not significant indicating that, all other variables held constant, there is no evidence of true occurrence dependence (simply the occurrence of a UI spell alters future spells).

Our results suggest that changing or implementing policies that target claimant personal characteristics is unlikely to affect the number of benefit weeks claimed in subsequent UI claims. Most of the variation in the duration was due to macro- and micro-economic conditions such as the local unemployment rate and when the claimant was unemployed. Employment histories were also not significant predictors of future weeks of UI benefit claims.

Future research should include data on the number and intensity of workforce agency services on future claimant labor market outcomes. If workforce agencies wish to decrease the amount of UI benefits received, they will be able to tailor their services to claimants that have specific past and future labor market histories. For example, claimants who experience their first claim during high levels of unemployment and have highly specialized skills may be more difficult to employ as job opportunities shrink and they may take lower paying jobs to ease the financial burden. However, jobs during economic downturns tend to be of lower quality (Kahn, 2011) and the claimant may claim more benefits during their second claim to spend time looking for a higher quality job. Placing this claimant in workshops or classes where they can broaden their skills and abilities may give more opportunities for better employment after that first claim. Further, workforce agency services may interact with economic conditions where certain services are more or less effective as the business cycle changes.

Several limitations should be noted. The length of time unemployed after the first claim was calculated using the number of quarters between the quarter of collecting benefits and the quarter after appearing in wage records again. There are typically 13 weeks in a quarter and the number of quarters was multiplied by 13 thus limiting the variability in the actual number of weeks unemployed. The Wyoming unemployment rate was substituted for those claimants without a Wyoming residence. Using the statewide unemployment rate does not tell us the economic conditions at the local (county) level. Future research could incorporate the unemployment rate in the claimant’s home county which would also be a proxy for the likelihood they could find employment in their home county. Finally, the R2 for males and females (.21 and .22, respectively) was relatively small. This means that around 80% of the variance in both models was accounted for by other variables. Future research could survey claimants regarding their experience with the UI system and may yield more fruitful information on such variables as reservation wage, likelihood of taking a job if offered, value of employment, and unemployment stigma.

Future research should also include examining the relationship of returning to the same employer and employer-offered benefits. For example, there may be an interaction between benefits offered and likelihood of returning in those industries where lay-offs are common due to seasonality (e.g., construction). R&P currently surveys a sample of employers in the state regarding the benefits they offer employees. More information regarding R&P benefit survey research can be found here: http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/benefits.htm.

References

Arranz, J.M., & Muro, J. (2000). New evidence on state dependence in unemployment histories.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice- Hall, Inc.

Braumoeller, B.F. (2004). Hypothesis testing and multiplicative interaction terms. International Organization, 58, 807-820.

Cappellari, L., Dorsett, R., & Haile, G. (2010). State dependence and unobserved heterogeneity in the employment transitions of the over-50s. Empirical Economics, 38, 523-554.

Card, D., & Levine, P.B. (2000). Extended benefits and the duration of UI spells: Evidence from the New Jersey extended benefit program. Journal of Public Economics, 78, 107-138.

Corak, M. (1993). Is unemployment insurance addictive? Evidence from the benefit durations of repeat users. Industrial & Labor Relations Review, 47, 62-72.

Doiron, D., & Gørgens, T. (2008). State dependence in youth labor market experiences and the evaluation of policy interventions. Journal of Econometrics, 145, 81-97.

Fishe, R.P. (1981). Unemployment insurance and the reservation wage of the unemployed. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 64, 12-17.

Gray, D., & McDonald, T. (2012). Does the sophistication of use of unemployment insurance evolve with experience? Canadian Journal of Economics, 45, 1220-1245.

Harris, P. (2014). The recent labor market downturn as a natural experiment, part 1: unemployment insurance (UI) claimant labor market behavior: length of benefit collection and the likelihood of exiting the labor market. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 50(8).

Heckman, J.J., & Borjas, G.J. (1980). Does unemployment cause future unemployment? Definitions, questions, and answers from a continuous time model of heterogeneity and state dependence. Economica, 47, 247-283.

Kahn, L.B. (2011). Job durations, match quality and the business cycle: What we can learn from firm fixed effects. Yale University.

Knabe, A, & Rätzel, S. (2011). Scarring or scaring? The psychological impact of past unemployment future unemployment risk. Economica, 78, 283-293.

Manning, P. (2012). Examining wage progression in Wyoming from 1992 to 2011. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 50(8).

Meyer, B.D. (1990). Unemployment insurance and unemployment spells. Econometrica, 58, 757-782.

Niedergesäss, M. (2012). Duration dependence, lagged duration dependence, and occurrence dependence in individual employment histories. (University of Tuebingen Working Papers in Economics and Finance No. 26).

Omori, Y. (1997). Stigma effects of nonemployment. Economic Inquiry, 35, 394-416.

Opp, K.D. (1979). Social evolution: Learning theory applied to group action. Theory and Decision, 10, 229-243.

Rothstein, J. (2011). Unemployment insurance and job search in the Great Recession. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. (Fall).

Ruhm, C.J. (1991). Are workers permanently scarred by job displacements? The American Economic Review, 81, 319-324.

van Ours, J.C., & Vodopivec, M. (2006). How shortening the potential duration of unemployment benefits affects the duration of unemployment: Evidence from a natural experiment. Journal of Labor Economics, 24, 351-378.