The Recent Labor Market Downturn as a Natural Experiment, Part 1:

Unemployment Insurance (UI) Claimant Labor Market Behavior: Length of Benefit Collection and the Likelihood of Exiting the Labor Market

Increasing the maximum number of weeks an individual can claim Unemployment Insurance (UI) benefits has been shown to increase the time spent unemployed, which can have negative consequences on the unemployment rate (Rothstein, 2011). On the other hand, an extension of UI benefits allows the unemployed worker more time to search for suitable employment with higher wages that better matches their knowledge and skills (Kahn, 2011). Using UI claims data before, during, and after the recent economic downturn, we found that the length of UI benefit collection affects the likelihood of leaving Wyoming’s labor market. Further, we found that the possibility of collecting extended UI benefits has little effect on a person’s work search intensity. We discuss workforce agency initiatives and program evaluation implications.

More on Migration and Unemployment Duration

Using data from the American Community Survey (ACS), Goetz (2014) used regression analysis to determine if individuals who move for re-employment opportunities experienced a decrease in the duration of unemployment and a higher probability of re-employment. The author found that those who migrate spend significantly less time unemployed compared to those who remain in the same area. Further, it was found that they experienced a higher probability of becoming re-employed. The author posits that relocating would need to have a significant incentive (e.g., much higher wages) due to the cost of moving and an increased incentive to find work.

Reference

Goetz, C. (2014). Unemployment duration and geographic mobility: Do movers fare better than stayers? In Working Paper 14-41. N.p.: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Retrieved November 28, 2014, from https://ideas.repec.org

/p/cen/wpaper/14-41.html

According to the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER, 2010), the recent national recession lasted from December 2007 to June 2009. From 2005 to 2013, the amount of Unemployment Insurance (UI) benefits paid varied across the nation. In Wyoming, the UI trust fund remained solvent after it paid out $665.5 million between 2005 and 2013, while several other states borrowed money from the federal government to pay UI benefits. The research presented here is the first article in a three-part series examining UI claimants prior to, during, and after the recent downturn. The purpose of this article is to examine people who exit Wyoming’s labor market (leavers) after UI benefit collection. Part II will examine the characteristics of those claimants who will use the UI system again in the future (repeat claimants). Part III will examine UI benefit duration and re-employment outcomes after UI benefit collection.

The purpose of this series is two-fold. First, in order to conduct successful and useful workforce program evaluation, UI claimant behavior should be understood in terms of individual labor market histories and the economic conditions when a claimant collects UI benefits. From a program evaluation standpoint, comparing groups across time will lead to bias due to unobserved characteristics between claimants, and capturing these characteristics strengthens program evaluation research. Second, the financial and human resources of workforce agencies are limited, and focusing on claimants who are likely to benefit from services should be a primary goal.

The results in this article suggest that claimants behave differently depending on economic and individual characteristics, which will influence workforce agency service direction. The three articles in this series explore UI claimant behavior in times of differing economic conditions and the effects of large-scale policy changes that affect the labor force, such as extended benefits.

A key responsibility of state workforce agencies is to assist unemployed individuals in finding work during unemployment. From a policy and statistical standpoint, the period examined in this article (2005 to 2012) provides a unique evaluation of the UI system and the effectiveness of state workforce agency services due to the high degree of variability in the number and length of UI benefit collection. Specifically, this includes a period of economic expansion (2005Q1 to 2008Q4), economic downturn (2009Q1 to 2010Q2), and gradual economic recovery (2010Q3 to 2012Q4). During these periods, policy changes to the UI system were implemented in response to changes in economic conditions. Due to the variability in the use of UI prior to, during, and after the recent economic downturn, many authors deem it a natural experiment (Kahn, 2011; Rothstein, 2011). A natural experiment is one where clusters of individuals are exposed to treatment or control conditions that are determined by nature or laws and not induced by a researcher. A natural experiment is one way to evaluate large-scale policy changes and their effects on labor market activity (van Ours & Vodopivec, 2006).

In this article, the number of Wyoming’s UI claimants who left Wyoming’s labor market after UI benefit collection (leavers) is examined. Leavers are defined as those claimants who do not appear in Wyoming wage records again after the quarter in which they began receiving benefits. The leaver rate is the number of leavers divided by the total number of UI claimants. In order to understand the interstate migration patterns of individuals collecting Wyoming UI benefits, the number of leavers who appeared in partner states’ wage records is examined.

The number of UI claimants who permanently left Wyoming’s labor market grew from 15.0% in 2005 to 33.6% in 2012; local and regional economic conditions were likely contributing factors. This increase may also be due in part to the fact that claimants who left Wyoming’s labor market in more recent years have not had as much time to establish re-employment. Results presented in this article suggest that the length of UI benefit collection may affect re-employment efforts. Just after eight weeks of UI benefit collection and just before benefit exhaustion, the number of claimants who leave the labor market increases. Workforce agencies should consider focusing their services on claimants who can truly benefit from services and implementing sound program evaluation to better allocate resources.

Overview of Unemployment

Insurance (UI) Benefit Program

The UI system is designed to assist individuals and households affected by job loss with supplemental income during unemployment, allowing the individual to invest time and money searching for work. Several criteria are required in order for an individual to be eligible to receive UI benefits. First, an individual must earn adequate wages during the base period (the first four of the last five calendar quarters). Second, the job loss occurred through no fault of the individual; for example, those individuals who quit a job are not eligible. Third, the individual must be able, available, and actively seeking employment during the time of benefit collection.

Throughout the UI system there are several types of claims. The two types of claims used in this article are initial claims and continued weeks claimed. An initial claim occurs when an individual approaches the Department of Workforce Services (DWS) regarding eligibility for UI benefits. If an individual is considered eligible for UI benefits and begins to receive those benefits, then each week is considered a continued claim week. Normally, the maximum number of weeks an individual is able to claim during his benefit year in Wyoming is 26 weeks. It should be noted that the number of benefit weeks depends upon individual circumstances, such as wages prior to initial claim, and may not reach the maximum of 26 weeks.

Literature Review

According to Wen (2010), 37,312 individuals in Wyoming lost their jobs and collected UI benefits in 2009. More than two-thirds of these individuals were men, and 59.5% of all claimants had only a high school education. Geographical locations where mining is a substantial piece of economic activity were hit especially hard. UI benefits not only assist in sustaining the individual and household during job loss but also offset the negative economic impact during a downturn by retaining jobs in a particular local economy. Leonard (2010) found that UI benefit payments paid to claimants in 2009 were estimated to account for approximately 990 jobs retained as a result of UI claimants’ ability to continue to spend in the state.

Given that UI benefits help the individual and the economy as a whole, research on individual labor market behavior before and after UI benefit collection has received much attention. Past research suggests that interacting with the UI system (and the unemployment experience itself) alters future employment, unemployment, and use of unemployment insurance (Corak, 1993; Heckman & Borjas, 1980). Using UI program data from 1971 to 1990, Corak found the number of past UI claims filed may contribute to a “scarring” effect on claimants’ future interaction with the unemployment insurance system. The author noted that this result is possibly due to the eroded stigma associated with collecting UI benefits and also an increased familiarity with the UI system, application, dispute, and job search processes. This “scarring” is the lasting effect unemployment has on future labor market success and possible changes in psychological well-being (Knabe & Ratzel, 2009).

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), signed in February of 2009, allocated federal money to provide up to 13 weeks of extended benefits. Extending UI benefits has received much attention by researchers and policy-makers in terms of its effects on the unemployment rate, job creation, and re-employment of UI claimants. Card and Levine (2000) found that after New Jersey implemented a 13-week benefit extension, UI benefit collection increased by one week over the course of the claim. The authors found that when claimants knew they could receive an increase in the maximum number of UI benefits, they reduced their job search intensity and continued to claim more benefit weeks. The authors expected that the spike in the UI leaving rate (the number of claimants who leave UI for employment) just before benefit exhaustion in the presence of extended benefits would be less pronounced due to the possibility of receiving further UI benefits. However, the authors found notable spikes in leaving UI just prior to benefit exhaustion both in the presence and absence of extended benefits. These results indicate that the UI leaving rate declines over the course of the claim, and that other factors besides job search intensity are contributing to the spike in the UI leaving rate in the weeks prior to benefit exhaustion during a time when extended benefits are available compared to when they are not.

Using data from the Current Population Survey (CPS), which is a monthly household survey conducted by the Census Bureau for the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) designed to gather data on labor force participation (employment and unemployment) and other labor force characteristics, Rothstein (2011) found that extended UI benefits reduced the rate of re-employment, but the effect was relatively small. Rothstein suggests that extending UI benefits during tough economic times allows a worker enough time to find employment when jobs are scarce. Further, the quality of job matches when economic conditions are poor are typically lower compared to good economic times (Davis, Haltiwanger, & Schuh, 1996), and several researchers suggest that an increase in benefit length allows an unemployed worker more time to find employment which best matches their human capital (Bowlus, 1995; Kahn, 2011).

The research discussed above forms two different interpretations of the use of the UI system and implementation of extended benefits. On the one hand, increasing the maximum number of weeks an individual can claim benefits has been shown to increase the time spent unemployed which can have negative consequences on the unemployment rate (Rothstein, 2011). On the other hand, an extension of UI benefits allows the unemployed worker enough time to search for suitable employment with higher wages that better matches their knowledge and skills (Kahn, 2011).

Methodology

The data used in this article are initial and continued UI claims for which a claimant collected at least one week of UI benefits between first quarter 2005 (2005Q1) and fourth quarter 2012 (2012Q4). Literature suggests that interacting with the UI system, and the unemployment experience itself, alters future employment, unemployment, and use of unemployment insurance (Heckman & Borjas, 1980). In an attempt to limit the sample to first time UI claimants, all individuals who received Wyoming UI benefits prior to 2005 were excluded from these analyses. However, controlling for prior use of UI in another state is not possible with current Research & Planning (R&P) datasets.

R&P maintains a UI Wage Records database, which includes quarterly wages for approximately 92% of Wyoming workers. Wage data were used to compile labor market participation before and after collecting UI benefits. If a claimant was not re-employed by 2013Q3, his wage data was set to zero. Further, R&P currently has data sharing agreements with 10 partner states (Alaska, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, and Utah), which allows R&P to monitor Wyoming’s labor into and out of other states. Wage records from other states include wages through 2012Q4, with the exception of Oklahoma, which only includes wages through 2011Q4. If an individual had wage records in another state after the quarter in which he began receiving UI benefits, he was considered employed in that state.

|

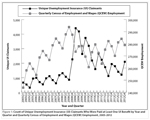

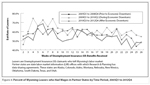

Figure 1 shows the number of unique claimants by year and quarter who were paid at least one week of UI benefits, as well as the level of employment measured by the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW). The pattern of seasonality in Wyoming’s labor market is clear, with increases and decreases depending upon time of year, particularly between 2005Q1 and 2008Q2. From 2005Q1 to 2012Q4, 2009Q1 saw the largest number of individuals who claimed at least one week of UI benefits (4,406). The number of individuals with at least one week of UI benefits remained over 1,500 through quarter 2011Q2. A total of 53,080 unique individuals were included in the analyses.

Results

In this article, leavers are defined as Unemployment Insurance (UI) claimants who did not appear in Wyoming wage records again after the quarter they began receiving benefits. The leaver rate is the number of leavers divided by the total number of UI claimants.

|

|

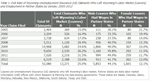

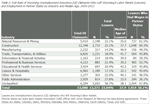

The number of leavers and the percentage of those leavers by gender who were found in partner states’ wage records are shown in Table 1 and Figure 2. In 2005, 58.1% of all leavers with wages in partner states were males, and 41.9% were females. In 2009, the proportion of male leavers with wages in other states (83.1%) was higher than in any other year, while the proportion of females with wages in other states (16.9%) was lower than in any other year. For female leavers, the proportion peaked in 2005 (41.9%), steadily declined to a low in 2009 (16.9%), and has remained flat since 2010. Again, this may be due in part to the fact that claimants in earlier years had more time to become re-employed in Wyoming than claimants in more recent years.

|

For those claimants who filed a claim under an unclassified industry, 58.7% would become leavers after UI benefit collection (see Table 2). The unclassified industry designation is used when the firm does not provide information for proper North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) coding. Most of the firms in the “unclassified” industry are out-of-state companies. This large percentage can be partly explained by the number of nonresidents in an unclassified industry (91.5%) during this time period (not shown in Table 1). Nonresidents are defined as “individuals without a Wyoming-issued driver’s license or at least four quarters of work history in Wyoming” (Jones, 2002). This indicates that nonresidents may have migrated back to their home state after UI benefit collection.

For leavers in educational & health services, the median age was 42.2, which supports past R&P research that educational & health services has an older labor force compared to other industries (see Teacher Salaries in Wyoming which can be found at http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/occasional/occ7.pdf).

Harris (2012) found that when older individuals become unemployed and file for UI benefits, they are less likely to find employment after their claim than younger individuals. A total of 697 claimants in educational and health services left the labor force and less than half went to work in a partner state, which may indicate that these claimants decided to retire after UI benefit collection. Additionally, 60.7% of all leavers were nonresidents and of those, 63.5% had wages in partner states. By comparison, 39.3% of all leavers were residents, 44.9% of whom had wages in a partner state.

As shown in Table 2, the median age of leavers in leisure & hospitality was 32.1. This industry accounted for 17.1% of all leavers. The highest rates of leavers who had wages in a partner state were found in natural resources & mining (61.5%) and construction (60.3%), while the lowest was found in public administration (36.1%). This suggests that there were more employment opportunities in a partner state for leavers from natural resource & mining and construction compared to other industries.

|

The data in Table 3 illustrate the differences in exit rate within Wyoming’s 23 counties. The largest exit rate was for those claimants who had an out-of-state address (57.4%). Again, this large percentage indicates that workers who came to Wyoming from another state were more than half as likely to leave the state after claiming benefits. Further, 63.5% of non-residents who left had wages in partner states, indicating that nonresidents looked for work in other states.

In terms of Wyoming’s counties, Sublette County had the highest leaver rate (19.1%), and 48.6% of all leavers from Sublette County had wages in partner states. Due to the energy production in Sublette County, companies may have moved jobs to partner states as energy production decreased in Sublette County and increased in other states. For example, in the northwestern region of North Dakota, the oil boom from the Bakken formation began to have substantial impacts on the average wage beginning in 2005 compared to surrounding counties up to 400 miles away (Batbold & Grunewald, 2013), which may have enticed workers to migrate to North Dakota.

In 17 of Wyoming’s 23 counties, females claimed more benefit weeks than males on average. Goshen and Platte counties saw the largest difference in length of UI benefit collection between males and females (a difference of 11.9 and 10.2 weeks, respectively). Past research has shown that females remain unemployed for longer periods of time, which may be due to Wyoming’s economy being dominated largely by male dependent industries such as natural resources & mining and construction (Harris, 2012). Further, females could be collecting UI for longer periods due to family responsibilities and other outside influences rather than economic conditions. Females are also less likely to search for and accept jobs that are gender-atypical and stereotypically performed by males (Kulik, 2000).

In order to examine whether length of benefit collection affects the exit rate during different economic and policy conditions, three periods were used: prior to (2005Q1 to 2008Q4), during (2009Q1 to 2010Q2), and after (2010Q3 to 2012Q4) the economic downturn in Wyoming. As is typical during economic downturns, policy was enacted to extend the length of UI benefits at either the state and/or federal level. As outlined in the introduction of this article, the possibility of collecting an increased number of UI benefit weeks may have an effect on job search intensity.

|

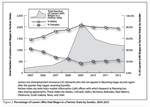

Figure 3 shows that the period after the downturn (2010Q3 to 2012Q4) saw a higher leaver rate than the other two periods. The results displayed in Figure 3 may be due in part to the fact that claimants in later years had less time to find re-employment in Wyoming than claimants in earlier years. During weeks three through eight of UI benefit collection, the leaver rate remained relatively stable within the three periods. Just after eight weeks (two months) of collecting benefits during the downturn, the leaver rate increased by 6.7% with smaller increases in the other two periods. This suggests that when economic times are tough, claimants may try to look for work at the beginning of the claim and then decide to search for employment in other labor markets or leave for other reasons – such as retirement or returning to school – due to poor job prospects in their current labor market.

As mentioned previously, an individual is notified two weeks before benefit exhaustion as to whether he can potentially receive extended benefits. For claimants who are eligible for 26 weeks of unemployment benefits, this notification would occur during the 12th week of benefit collection. As seen in Figure 3, between the 12th and 21st week of UI collection for all periods, the leaver rate shows little change. During the downturn, the leaver rate shows the least variability between UI weeks claimed. This result suggests that if individuals are notified that they may receive additional benefits after exhaustion, claimants show a certain level of inactivity when deciding to exit the labor market during tough economic times. This may be due to the prospect of receiving extended benefits or the limited number of jobs available during an economic downturn.

Both before and after the downturn (during times of better or improving economic conditions), individuals begin to exit the labor market at an increasing rate five weeks before benefit exhaustion (21 weeks). Strong spikes in leaver rate just prior to UI benefit exhaustion (25 weeks) were observed before (9.1%) and during (7.7%) the downturn. However, the spike after the downturn was smaller (5.0%), indicating that when economic times are improving and extended benefits are available, such as after the downturn, claimants are less likely to leave the labor market when facing exhaustion. Due to more weeks available, claimants have more time available to search for a job before they lose UI benefits and may continue to look for better job matches as job growth improves.

|

Figure 4 shows the percentage of leavers who had wages in partner states by time period and length of UI benefit collection. Prior to and after the downturn, there was a substantial increase in the percentage of leavers just after the first month (fifth week) of UI benefit collection. However, during the downturn this increase occurred at the fourth week (one month) of UI benefit collection, one week sooner and was more pronounced. The percentage of leavers who had wages in other states increased from 45.8% in the second week to 74.5% in the fourth week during the downturn. The rate of employment in other states fluctuated substantially between the first 12 weeks of benefit collection both prior to (ranging from -12.3% to 15.6%) and during (ranging from -10.3% to 14.5%) the downturn. However, the rate of employment in a partner state after the downturn had only minor fluctuations ranging from -5.9% to 5.4%.

Just prior to benefit exhaustion, the number of individuals who gained employment in a partner state steadily decreased both prior to and after the downturn. These results indicate that an individual’s job search behavior is not altered by the availability of extended benefits. This effect also indicates that claimants continue to look for suitable employment that matches their knowledge and skills or remain in their current labor market until the number of jobs begins to increase. During the downturn and after 16 weeks of benefit collection (four months), employment in a partner state was higher than the other two periods. This finding suggests that people may be taking lower quality jobs in surrounding labor markets due to a declining economy, scarcity of jobs, and perception of fleeting opportunities.

Part 1 of this article focused on UI claimants who left Wyoming’s labor market after benefit collection and those who will become claimants again in the future by utilizing the natural experiment the recent economic downturn produced.

Professor Steven Davis of the University of Chicago expressed disappointment in the federal government’s willingness to extend unemployment benefits during the recent economic downturn without instituting new workforce programs and requiring rigorous experimentation to evaluate new and existing programs for their effectiveness at putting people back to work (Davis, 2009).

Workforce agencies often have limited resources to assist claimants in finding work during and after UI benefit collection and channeling those resources to claimants that could use services would likely result in more effective workforce programs. For example, claimants exit the labor market at an increasing rate after the first two months of UI benefit collection and when extended benefits are available this rate is even higher. Further, just before a claimant exhausts benefits, the rate of labor market exit spikes. Evaluating specific workforce programs on their success of keeping workers in a particular labor market may be warranted. As Wyoming’s population continues to age, program evaluation of this type would be especially useful to help prevent the outflow of younger workers who become discouraged looking for work within the state. For example, do those claimants who receive certain services at a specific intensity find suitable (and long lasting) employment in Wyoming compared to claimants who receive little or no services?

A final implication of the current research is the applicability of using UI claimant data in other types of program evaluation. Currently, R&P is in the process of conducting an evaluation of the Hathaway Scholarship Program, a merit-based scholarship which was made available to high school graduates beginning in 2006/07 and provides funding to attend post-secondary institutions in Wyoming. The primary goals of the Hathaway Scholarship Program, as with many merit-based scholarships, are to improve secondary and post-secondary student outcomes, and retain educated youth in the labor market after they graduate from their post-secondary institution. The Wyoming legislature has mandated that the Hathaway Scholarship Program be evaluated for its effectiveness in reaching these goals. R&P can investigate Hathaway Scholarship Program graduates who enter the labor force and become UI claimants. A potential research question may include: are Hathaway Scholarship Program graduates performing better (e.g., earning higher wages, increased employer tenure) in the labor market compared to individuals who received other types of funding (e.g., federal loans, other scholarships)? However, as the present research demonstrates, knowledge of the specific economic conditions and claimant history is crucial in understanding the inflow and outflow of labor within the UI system.

The program evaluation methods mentioned above are often completed using quasi-experimental research designs. Quasi-experimental designs differ from true experiments in that participants are not randomly assigned to receive the treatment – in this case, receive services. The U.S. Department of Labor requires state use of UI wage record data for Workforce Investment Act (WIA) program evaluation. The Government Accounting Office (GAO) found that using UI wage record information to provide outcome information was reliable and Congress may wish to consider requiring all WIA participants be tracked this way (GAO, 2004). In 2009, the GAO published a report recommending the use of quasi-experimental designs as the most practical and rigorous method to evaluate the effectiveness of governmental programs. Further, proper training of DWS staff on general research methods and statistical concepts is warranted so critical interpretation of labor market research is performed.

It should be noted that the analyses presented in this article were performed using data from Wyoming and partner states only. Around the country, labor markets do not function the same way, so caution should be taken when generalizing results to different labor market populations. Further, R&P could not control fully for claimants who have used UI systems in other states, which limited the ability to fully ensure that individuals were first-time claimants.

The second article in this series will examine the repeat use of the UI system and employment outcomes.

References

Batbold, D., Grunewald, R. (2013, July 1). Bakken activity: How wide is the ripple effect?

Bowlus, A.J. (1995). Matching workers and jobs: Cyclical fluctuations in match quality. Journal of Labor Economics, 13, 335-350.

Bullard, D., Gallagher, T., Glover, T., Harris, P., Holmes, M., Knapp, et al. (2014). Teacher salaries in Wyoming: Competitive enough to retain the best? (Occasional Paper No. 7). Retrieved April 30, 2014, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/occasional/occ7.pdf

Card, D., & Levine, P.B. (2000). Extended benefits and the duration of UI spells: Evidence from the New Jersey extended benefit program. Journal of Public Economics, 78, 107-138.

Corak, M. (1993). Is unemployment insurance addictive? Evidence from the benefit durations of repeat users. Industrial & Labor Relations Review, 47, 62-72.

Davis, S.J. (2009). Getting back to work. Forbes. Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/2009/10/14/unemployment-efca-health-care-opinions-contributors-steven-j-davis.html

Davis, S.J., Haltiwanger, J., & Schuh, S. (1996). Job Creation and Destruction. MIT Press.

Government Accountability Office (2004). Workforce Investment Act: States and local areas have developed strategies to assess performance, but Labor could do more to help (GAO Publication No. 04-657). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Government Accountability Office (2009). Postsecondary education: Many states collect graduates’ employment information, but clearer guidance on student privacy requirements is needed (GA 1.13:GAP-10-927). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Harris. P. (2012). Dynamics of unemployment spells: A look at the trends before, during, and after the Great Downturn. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 49(12). Retrieved February 5, 2014, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/trends/1212/toc.htm

Heckman, J.J., & Borjas, G.J. (1980). Does unemployment cause future unemployment? Definitions, questions, and answers from a continuous time model of heterogeneity and state dependence. Economica, 47, 247-283.

Jones, S. (2002). Defining residency for the Wyoming workforce. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 39(11). Retrieved May 23, 2013, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/1102/a1.htm

Kahn, L.B. (2011). Job durations, match quality and the business cycle: What we can learn from firm fixed effects. Yale University.

Knabe, A., & Ratzel, S. (2011). Scarring or scaring? The psychological impact of past unemployment and future unemployment risk. Economica, 78, 283-293.

Kulik, L. (2000). Jobless males and females: A comparative analysis of job search intensity, attitudes toward unemployment, and related responses. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73, 487-500.

Leonard, D. (2010). Estimating the impact of unemployment insurance benefit payments on Wyoming’s economy. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 48(8). Retrieved September 18, 2012, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/0810/toc.htm

National Bureau of Economic Research. (2010). Retrieved September 19, 2012, from http://www.nber.org/cycles/sept2010.html

Rothstein, J. (2011). Unemployment insurance and job search in the Great Downturn. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. (Fall).

van Ours, J.C., & Vodopivec, M. (2006). How shortening the potential duration of unemployment benefits affects the duration of unemployment: Evidence from a natural experiment. Journal of Labor Economics, 24, 351-378.

Wen, S. (2010). Wyoming unemployment insurance benefit payments reach record high in 2009. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 47(2). Retrieved September 18, 2012, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/0210/a1.htm