Job Attainment and Wages of Wyoming Vocational

Rehabilitation Participants

This article examines the success rate of participants who have completed the Wyoming Department of Workforce Services’ Vocational Rehabilitation program. Clients with successful closures had a higher rate of job attainment one year after closure date (73%) than those with unsuccessful closures (43%).

The purpose of the Wyoming Department of Workforce Services’ Vocational Rehabilitation (VR) Division is to help “people with disabilities establish and reach vocational goals that help them become productive working citizens.” (Wyoming Department of Workforce Services). In this article, Research & Planning (R&P) examines the outcome over time on Wyoming VR participants’ employability and earnings based on closure status (whether successful or unsuccessful; see Definitions) and months of participation. Note: This study does not quantify the impacts of the VR program, such as the employment outcomes of people with or without the VR program’s existence. As VR programs exist in all states, there is no way to identify a group of people with similar disabling conditions who received no VR services.

Definitions

Closure: The date at which the VR program closed a participant’s file. This can happen for many reasons.

Successful closure: For the purposes of this study, a successful closure is termed closed rehabilitated and all other closure types are considered unsuccessful.

Unsuccessful closure types include:

Closed, not accepted for VR services, from the applicant status.

Closed, not accepted for VR services, from extended evaluation.

Closed, not rehabilitated, after individualized written rehabilitation program initiated.

Closed, not rehabilitated, before individualized written rehabilitation program initiated.

Closed from the pre-service listing.

This study combines two main sources of information: VR program data and Wyoming Department of Employment administrative databases, which include wage records and demographic information (see related article).

This study found the rate of job attainment was substantially higher for clients with successful closures (72.6% employment one year after closure date) compared to clients with unsuccessful closures (43.2%). However, the rate of successful closures was relatively low (35.8%). Successful completion often leads to lower levels of costs for publicly provided supportive services such as Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI).

Previous longitudinal studies on the efficacy of the VR program have been conducted, including a national survey conducted by Hayward & Schmidt-Davis for the Rehabilitation Services Administration (RSA). The study began in January 1995 and was completed in January 2000. The survey consisted of 8,500 VR participants tracked over three years. Using a cohort design, researchers randomly selected 25% of the sample from the population of people when they applied to VR, 50% of the sample from the population of people who were already receiving services, and 25% of the sample from the population who were exiting or had exited from VR services (Hayward and Schmidt-Davis). The study used an initial interview/survey and a three-year follow-up survey. “The study differs from prior studies of the VR program in that it offered the opportunity to collect extensive data on individuals, services, and outcomes, expanding previous analytical bases and allowing a more thorough assessment of VR results than had previously been possible.” (Hayward and Schmidt-Davis, ES-2). “At the end of the VR longitudinal study’s data collection period, 17% of the study population was continuing to receive VR services three years after they entered the study, 45% had achieved an employment outcome, and 21% had exited VR after services without an employment outcome.” The study found that “persons who receive VR services were likely to achieve a competitive employment outcome if:

- they had higher gross motor function;

- they had higher cognitive function;

- they were working at application for VR services;

- they had higher earnings at their most recent job prior to VR application;

- they had greater knowledge of different jobs;

- they had greater knowledge of the nonmonetary

- benefits of jobs.” (Hayward and Schmidt-Davis, ES-6).

While the RSA study provides thorough information regarding the factors influencing employability of VR participants, it is based on a national sample of the VR participants and is subject to response bias. Consequently, it is not clear if or to what extent national study findings are applicable at the state and local level. This R&P study captured employment and wage outcomes from administrative databases encompassing the vast majority of participants and avoided some of the data collection problems and costs associated with survey collection methods. This analysis offers an example of a way relevant state and local research may be conducted at a much lower cost than through a survey-based approach.

A U.S. Government Accountability Office report (GAO, 2005) examined the performance of VR participants in fiscal year 2003. The study found that nationally, one-third of VR participants who exited a program in FY 2003 obtained employment, and this rate varied significantly among state VR agencies. For Wyoming, 38.3% of participants “exited with employment, after services under an employment plan.” (GAO, p. 47). This figure differs from the results of the R&P research (43.2%) in that the GAO study uses VR program data and examines employment at closure, while the R&P research relies on wage records and examines the first four quarters after closure.

The GAO initiated another study to identify ways to improve the VR program’s ability to benefit the subset of VR clients who were Social Security Administration (SSA) beneficiaries (GAO, 2007). The analysis group consisted of SSA beneficiaries who completed a VR program between 2001 and 2003. The GAO (2007, p. 3) analyzed outcomes by state agency using three earnings outcomes:

- the percentage of beneficiaries with earnings during the year after VR,

- the average beneficiary’s annual earnings level during the year after VR, and

- the percentage of beneficiaries that left the disability rolls by the close of 2005.

Results for each state agency were not shown individually. The results indicated, “The proportion of beneficiaries with earnings during the year after their completion of the VR program ranged from as little as 0% in one state agency to as high as 75% in another. Similarly, average annual earnings levels among those SSA beneficiaries with earnings varied across state agencies from $1,500 to $17,000 in the year following VR. Additionally, the proportion of SSA beneficiaries who left the disability rolls varied greatly among agencies, with departure rates ranging anywhere from 0 to 20%.” A significant result was that “state unemployment rates and state per capita income levels accounted for a substantial proportion – as much as one-third – of the differences between state agencies’ VR outcomes for SSA beneficiaries.” (GAO, 2007. p.4).

Another longitudinal study using wage records to assess the efficacy of the VR program was conducted in Ohio in 2004 (Gordon, Schaff, & Shaw). The study found that participants with closures within the 1993-1999 time periods, the competitive employment rate (not employed in sheltered workshops or subsidized businesses, etc.) ranged from 74 to 81% after one year, and 68 to 70% after three years. (Although calculated slightly differently, these findings were similar to the R&P study’s findings of 73% employment for participants with successful closure one year after the closure date). The authors stated, “The practical, general lesson to be learned from this project for workforce development is that wage records can be used to assess program outcomes. Wage records offer a viable alternative to traditional follow-up studies that often prove to be difficult, limited in coverage, and costly. The use of wage records affords a way to do such work efficiently and effectively – that is, to ‘work smarter’ in developing outcome measures that can serve to guide future investments in the workforce.” (Gordon et al., p. 41).

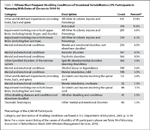

Given the nature of the data, the research strategy would require measuring outcomes that would not be present had the program not existed. A recent study (Leonard, 2009) conducted by R&P on a similar topic represents an example of this research strategy. The analysis focused on occupational injuries (Workers’ Compensation claimants), and the treatment thereof, and used the same administrative and wage records databases used in this study. Ideally, a matched control group of non-participants would be created using methods similar to Leonard’s. However, due to the lack of access to detailed medical information on the population in general, this would prove problematic for this study. Additionally, the VR participants differ from the worker compensation claimants in Leonard’s study as all employed persons are exposed to risks associated with the workplace and have the potential to become a workers’ compensation claimant. Most of the population is not likely to have a medical condition severe enough to be eligible for VR programs, at least not within a specific category of disability. A frequency of the major disabling conditions for the participants in this study is shown in Table 1.  For 11.5% of the participants, the major condition is not recorded. Additionally, for many of the 15 most frequently occurring disability codes, the descriptions are rather vague. Along with the lack of medical information on the general population, this prevents the establishment of a non-participant control group.

For 11.5% of the participants, the major condition is not recorded. Additionally, for many of the 15 most frequently occurring disability codes, the descriptions are rather vague. Along with the lack of medical information on the general population, this prevents the establishment of a non-participant control group.

This study compares the long-term effects of VR training on participants with a successful closure to those with an unsuccessful closure as defined by the program. To examine longitudinal outcomes, VR participants completing the program between January 1994 and December 1996 composed the analysis group. In the case of individuals with multiple closures, only the latest closure was examined. Participants with closure statuses of death, no disabling condition, or no impediment to employment were excluded from the analysis (253 people). Given these parameters, the data set contained 4,149 participants.

The data were categorized for analysis in two ways:

- Participants were categorized by closure status. A closure type of closed rehabilitated was categorized as a success, with all other closure types categorized as unsuccessful.

- Participants were categorized by the length of time they received VR services. This was termed months of participation and was defined as the number of months between the application date and the closure date.

Ideally, a start date of participation would be used rather than date of application, but this date was not captured in the VR program dataset. The reason for this method of categorization is that participants may leave the program for a variety of reasons. For example, a participant may have participated in the program long enough to have obtained the requisite skills for employability, then left the state for employment without notifying the VR program, and therefore would have likely been categorized as an unsuccessful closure. Four intervals of months of participation were analyzed: 0 to 3 months, 4 to 12 months, 13 to 24 months, and 24 or more months.

Within these two categories, the success rate of participants was calculated. Quarterly wage records were then used to calculate the number of participants who did and did not earn wages in Wyoming after their closure date, total wages, total quarters worked, total transactions, the average quarterly wage per participant, and the average number of employers per participant. This was examined at three intervals all starting the quarter following closure: 1, 5, and 10 years after closure. For the closure status category, the results were further partitioned by gender and age group. Wage data were inflation-adjusted using the Consumer Price Index (BLS, 2009). The base year for real wages was 2007.

Lastly, the economic conditions in Wyoming from 1994 through 2009 were briefly discussed to provide context regarding VR participants’ employment outlook. While the focus of this article is the long-term impact of the VR program, the success rate of 2007-08 participants was examined to see if this rate changed substantially.

Results

Closure Type Categorization

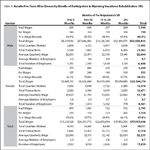

Approximately two-thirds (64.2%) of those entering the VR program did not complete the program successfully, regardless of gender.  The age distribution between successful and unsuccessful participants was similar. Neither age nor gender seemed to have substantial influence on whether a participant successfully completed the program (see Table 2).

The age distribution between successful and unsuccessful participants was similar. Neither age nor gender seemed to have substantial influence on whether a participant successfully completed the program (see Table 2).

Participants who completed the program successfully were much more likely to have earned wagesafter closure (see Table 3). One year after closure, 72.6% of successful participantsappeared in the Wage Record Database compared to 43.2% of those who did not complete the program successfully. Ten years after closure, the percentages were 83.9% and 65.3%, respectively.

One reason for an unsuccessful closure is “Unable to locate or contact or moved,” which may mean some participants had wage records in another state. Regardless, the VR program seems to have a strong positive influence on future employability.

When comparing quarterly wages between the two groups, successful participants tended to earn more income in the first four quarters after closure than participants with an unsuccessful  completion. Table 4 demonstrates that in the 12 combinations of age and gender that were compared, participants who successfully completed the program earned more income in 10 of the comparisons than participants who did not successfully complete the program. For example, men in the 35 to 44 age group who successfully completed the program earned $2,990 on average per quarter compared to $2,605 for their unsuccessful counterparts. While not as dramatically, this relationship tended to hold true at the five-year mark as well. The average quarterly wage per participant is normally distributed around the overall mean ($2,051).

completion. Table 4 demonstrates that in the 12 combinations of age and gender that were compared, participants who successfully completed the program earned more income in 10 of the comparisons than participants who did not successfully complete the program. For example, men in the 35 to 44 age group who successfully completed the program earned $2,990 on average per quarter compared to $2,605 for their unsuccessful counterparts. While not as dramatically, this relationship tended to hold true at the five-year mark as well. The average quarterly wage per participant is normally distributed around the overall mean ($2,051).

Generally, participants with successful closures tended to have fewer  employers on average, which suggests they had a higher retention rate with employers (Tables 3-6). This did not hold true for the most senior age group. However, the number of observations was small – 58 successful and 48 unsuccessful participants in the 10-year, after-closure period (see Table 6). Therefore, no strong conclusions regarding the most senior age group can be generalized.

employers on average, which suggests they had a higher retention rate with employers (Tables 3-6). This did not hold true for the most senior age group. However, the number of observations was small – 58 successful and 48 unsuccessful participants in the 10-year, after-closure period (see Table 6). Therefore, no strong conclusions regarding the most senior age group can be generalized.

VR participants, regardless of whether the program was completed successfully, lagged well behind in quarterly wages compared to the overall Wyoming population in all age  categories, with the possible exception of the 19-and-under age group (see Table 7). Male participants in this group, regardless of closure status, actually earned more wages than the overall wages earned in the state. This may have been due to the fact that overall wages for this age category were generally low. Across gender, the wage replacement percentage generally dropped as participants aged.

categories, with the possible exception of the 19-and-under age group (see Table 7). Male participants in this group, regardless of closure status, actually earned more wages than the overall wages earned in the state. This may have been due to the fact that overall wages for this age category were generally low. Across gender, the wage replacement percentage generally dropped as participants aged.

Months of Participation Categorization

There are numerous factors that determine the length of participation in the VR program such as a participant’s severity of impairment and willingness to strive to achieve a successful completion to the program. One possibility is that the longer the time period of participation the more likely the participant is to obtain employment, and perhaps earn higher wages. The average duration of participation was 15 months for this dataset, while the median was 11 months.

The percentage of participants who obtained employment averaged  53.7% across all participants one year after closure.This percentage did not vary by gender, nor months of participation, with the possible exception of those who participated 0 to 3 months (49.8%). Five years after closure, the overall percentage of participantsfound in the Wage Records Database increased to 67.4% (see Table 8). There are no clear-cut trends in the percentage of participants with wages, average quarterly wages, or average number of employers across the four months of participation categories.

53.7% across all participants one year after closure.This percentage did not vary by gender, nor months of participation, with the possible exception of those who participated 0 to 3 months (49.8%). Five years after closure, the overall percentage of participantsfound in the Wage Records Database increased to 67.4% (see Table 8). There are no clear-cut trends in the percentage of participants with wages, average quarterly wages, or average number of employers across the four months of participation categories.

Wyoming Economic Conditions (Unemployment Rate) from 1994 through 2009

In periods of economic volatility and instability, external economic factors may be the main determinant of an individual’s employment, overwhelming all other factors.

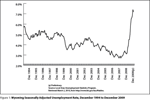

Over the period being discussed, Wyoming has had a relatively low and stable unemployment rate compared to the national rate. Across this period, the average monthly unemployment rate in the state was 4.3%,  with a low of 2.7% in January 2008, and a high of 7.5% in December 2009 (Preliminary; Bureau of Labor Statistics). Wyoming lagged behind most other states in regard to the impact of the recession, with unemployment rates not exceeding 5.0% until June 2009 (see Figure 1). Therefore, the conclusion is that external economic factors did not unduly influence VR participants’ employment prospects.

with a low of 2.7% in January 2008, and a high of 7.5% in December 2009 (Preliminary; Bureau of Labor Statistics). Wyoming lagged behind most other states in regard to the impact of the recession, with unemployment rates not exceeding 5.0% until June 2009 (see Figure 1). Therefore, the conclusion is that external economic factors did not unduly influence VR participants’ employment prospects.

2007-08 Participants in Comparison

While the main objective of this study was to examine the long-term impact of the VR program, it is also useful to briefly compare participants in the 1994-96 period to a more recent set of participants (2007-08). Roughly two-thirds of program participants with closure dates within the 1994-96 period did not complete the program successfully (see Table 2A). Additionally, participants with successful outcomes were more likely to appear in the Wage Records Database. One question asked was how do more recent program participants fare in terms of program completion and wage earnings?

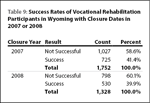

To address this question, participants with closure dates within the 2007- 08 period were examined (see Table 9). The success rate of the program has increased compared to the 1994-96 period. The overall effect may be even greater given that the definition of success is more rigorous in the later period. Success in both periods was determined as having a type of closure of “03.” However, the definition of this closure type in the earlier period was closed rehabilitated, while in the later period it was exited with an employment outcome. Given that in the later period there was also a closure type of “04” defined as exited without an employment outcome, after receiving services, the later period’s definition of success was more restrictive.

08 period were examined (see Table 9). The success rate of the program has increased compared to the 1994-96 period. The overall effect may be even greater given that the definition of success is more rigorous in the later period. Success in both periods was determined as having a type of closure of “03.” However, the definition of this closure type in the earlier period was closed rehabilitated, while in the later period it was exited with an employment outcome. Given that in the later period there was also a closure type of “04” defined as exited without an employment outcome, after receiving services, the later period’s definition of success was more restrictive.

Further Research

A more complete analysis would include the wage records of surrounding states to fully capture the wages of participants who moved out of state after closure. These data are available for approximately the last five years.

Two elements of the vocational rehabilitation data have not yet been examined: the severity of the injury or disability and the type of rehabilitation provided. Also, this study examined only the wage records of participants after closure. It may be useful to look at participants’ work history prior to admittance to the VR program. By looking at the participants’ pre- and post-closure history, a measure of the replacement of prior wages could be calculated.

A cost-benefit analysis of the VR program could be conducted. The cost of each participant’s rehabilitation is included in the dataset, as well as some information regarding public assistance received. Combined with wage record data, the cost effectiveness of the VR program could be estimated.

Benefits to Using the Wage Records Database to Assess the Efficacy of the VR Program

Every three years, the Wyoming Division of Vocational Rehabilitation (DVR) must submit a statewide needs assessment that “must examine the need to establish, develop, or improve community rehabilitation programs within the state.” (Western Management Services, p. 3). Special attention must be given to four disability populations: veterans with disabilities, students in transition, participants with an acquired brain injury, and minorities with disabilities.

The use of the Wage Records Database could aid in the preparation of this assessment as it provides a less expensive means of wage data collection. For the 2009 report, surveys were used to collect wage information; this was an unnecessary re-doubling of efforts as these data are already captured by the UI Wage Records Database. Rather than gathering data from a small sample of VR participants, wage data for the vast majority of participants could be analyzed. In addition, the longitudinal nature of the data allows for long-term impact assessment that is not possible by any other means.

As an example of enhancements that the wage record data could provide, please see Table 14 in the 2009 Wyoming assessment publication. (Western Management Services, p. 19). This table lists the causes of disability, the number of participants in each category, and the percentage of the total participants. By using the wage record data, this table could be expanded to include the number of participants that appeared in the Wage Records Database before and after their respective closure dates along with the number of quarters worked and their average quarterly wages. For example, in the case of those 148 participants with an acquired brain injury (ABI) who had closure dates in calendar year 2007 or 2008, 92.6% had wage records prior to the quarter of their closure, and 56.1% had wage records post closure. Each cause of disability could be examined and ranked in terms of employment outcomes. These could be used to identify potential improvements in the VR program and to set benchmarks for improvement.

References

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Indexes Program. (2010). Table Containing History of CPI-U U.S. All Items Indexes and Annual Percent Changes From 1913 to Present. Available from ftp://ftp.bls.gov/pub/special.requests/cpi/cpiai.txt

Glover, W. (2003). An introduction to wage records applications. Released to States participating in the Wage Records Application Project, February 2003. Wyoming Department of Employment, Research & Planning. http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/staff/WRAP.pdf

Gordon, R., Schaff, M., and Shaw,G. (2004, May). Using wage records in workforce investments in Ohio. Monthly Labor Review, 127(5), 40-43. http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2004/05/art5full.pdf

U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2005, September). Vocational Rehabilitation: Better measures and monitoring could improve the performance of the VR program. (Publication No. GAO-05-865). http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d07521.pdf

Government Accountability Office. (2007, May). Vocational Rehabilitation: Improved information and practice may enhance state agency earnings outcomes for SSA beneficiaries. (Publication No. GAO-07-521). http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d05865.pdf

Hayward, B.J., Schmidt-Davis, H. (2003). Longitudinal study of the Vocational Rehabilitation Services Program final report 1: How consumer characteristics affect access to, receipt of, and outcomes of VR services. RTI International. Submitted to U.S. Department of Education, Rehabilitation Services Administration. Available at: http://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/eval/rehab/vr-final-report-1.pdf

Leonard, D. W. (2009). Methodology and results. In Ellsworth, P. (Ed.) Post-injury wage loss: A quasi-experimental design. (pp. 28-41) http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/post_injury/report.pdf

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. (2007). SA04 State income and employment summary – Wyoming. Retrieved May 15, 2007, from http://www.bea.gov/regional/spi/default.cfm

U.S. Department of Education. (1995). Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services. Rehabilitation Services Administration. RSA-PD-95-04. RSM-1250. Date: May 01, 1995. Subject: Announcement of OMB approval for Collection of Data in the Case Service Report (RSA-911). File received via e-mail from Pepin, J., Data Collection and Analysis Unit, State Monitoring and Program Improvement Division/RSA.

Western Management Services, LLC. (2010). Wyoming Assessment of Rehabilitation Needs 2009. Prepared for the Wyoming Division of Vocational Rehabilitation and the State Rehabilitation Council. Wyoming Department of Workforce Services.