Occupations, Earnings, and Career Opportunities

This article is the third in a three-part series discussing resident youths and nonresidents in Wyoming’s labor market. The previous two articles reviewed the increase in nonresidents in Wyoming’s labor force and the decline in resident youth employment, and employment trends at the county and industry levels. This article looks at the types of occupations for which these two segments of the population are hired and what they earn.

Wyoming employers have historically relied to some degree on nonresident workers. For this series of articles, nonresidents are defined as “individuals without a Wyoming-issued driver’s license or at least four quarters of work history in Wyoming” (Jones, 2002). The number and proportion of nonresidents working in Wyoming is influenced by economic trends. During times of economic expansion, Wyoming employers turn to nonresidents to fill vacancies when they have exhausted the local labor supply (Leonard, 2010). When the economy contracts, nonresidents leave Wyoming and return to their home states.

Resident youths are defined in this series of articles as those individuals age 19 and younger who possess a Wyoming driver’s license. Since 2008, the number and proportion of resident youths participating in Wyoming’s labor force has declined substantially, while the overall youth population has remained relatively flat (Moore, 2013a).

Wyoming’s economy expanded rapidly from 2005 to 2008. Then in first quarter 2009 (2009Q1), Wyoming’s economy contracted for five consecutive quarters. R&P has identified the period from 2009Q1 through 2010Q1 as an economic downturn because average monthly employment, average monthly wage, and total wages all decreased from previous-year levels for five consecutive quarters, according to the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (Moore, 2013b).

This article will discuss the specific types of occupations for which resident youths and nonresidents are hired, the wages they are paid, and potential training opportunities for Wyoming schools and employers.

Background

The two previous articles in this series identified the number of nonresidents and resident youths in Wyoming’s workforce since 2000, and the types of industries in which these two segments of the population were employed. This was accomplished by linking the Wyoming Wage Records database with driver’s license files in order to identify the demographics of Wyoming’s workforce. While linking these two databases provides a tremendous amount of rich detail, it is not possible to identify the specific occupations in which these two segments of the population worked. For example, R&P determined that 11,876 nonresidents were employed at any time in Wyoming’s construction industry in 2012. However, the existing administrative databases do not provide information on what types of occupations nonresidents in the construction industry worked.

In order to identify job characteristics that were previously unavailable, R&P designed and implemented a New Hires Survey. For each quarter since fourth quarter 2009 (2009Q4), the New Hires Survey has allowed R&P to capture detailed information on occupations, benefits, wages, full- or part-time employment status, education and licensing requirements, and necessary skills for Wyoming jobs (Knapp, 2013). New hires are defined as workers who had not previously worked for a particular employer since 1992, the first year for which wage records are available for analyses (Knapp, 2011).

By linking the results of the New Hires Survey with the Wage Records database and driver’s license files from the Department of Transportation, R&P is able to identify the types of jobs for which nonresidents and resident youths are hired, how much they are paid, the benefits they are offered, how long they worked at those jobs, the number of hours they worked, the types of skills required for those jobs, and more. Results from the New Hires Survey are available online at http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/newhires.htm.

Results from the New Hires Survey

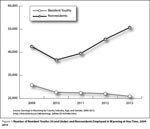

As mentioned in the first article in this series, the number of nonresidents working at any time in Wyoming has increased over the last several years, while the total number of resident youths working at any time has declined substantially (Moore, 2013a). Figure 1 shows the total number of nonresidents and resident youths working in Wyoming at any time from 2009 to 2013. During 2009 and 2010, while Wyoming was in the midst of an economic downturn, both population segments experienced a decrease in the total number of persons working. However, during the recovery period that has followed, the number of resident youths working at any time has continued to decrease, while the number of nonresidents working at any time has increased substantially.

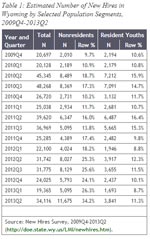

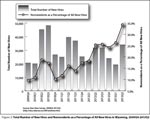

A similar trend can be seen among new hires. Figure 2 shows the estimated number of resident youth and nonresident new hires in Wyoming from 2009Q4 to 2013Q2. Because seasonal hiring patterns vary from quarter to quarter, this figure uses four-quarter moving averages, which helps to smooth out and more easily identify trends. The number of resident youth new hires has consistently decreased since 2010, while the number of nonresident new hires has increased.

R&P has been collecting information from the New Hires Survey since 2009Q4, when the state was in the midst of an economic downturn. During that quarter, Wyoming employers added 20,697 new hires; of those, 2,010 (9.7%) were nonresidents and 2,194 (10.6%) were resident youths (see Table 1). From 2010Q1 to 2011Q3, nonresidents and resident youths each made up a similar proportion of the total number of new hires during most quarters; for example, in 2011Q2, 16.0% of the 39,620 new hires were nonresidents, and 16.4% were resident youths. Since 2011Q4, however, the number of resident youth new hires has dropped considerably. During each quarter from 2012Q1-2013Q2, Wyoming employers added at least twice as many nonresident new hires as resident youth new hires. In 2013Q2, Wyoming employers added 11,675 nonresident new hires compared to 3,841 resident youth new hires.

The proportion of nonresidents among all new hires also increased significantly since the start of the New Hires Survey. In 2009Q4, nonresidents accounted for 9.7% of the 20,697 new hires. Since 2012Q2, nonresidents have accounted for approximately one in every four new hires during each quarter (see Figure 3). In 2013Q2, nonresidents made up 34.2% of all new hires.

Occupations and Wages

Many resident youths and nonresidents are hired to fill relatively low-paying jobs that are seasonal and require no education beyond a high school diploma. Of the top 10 occupations for nonresident new hires from 2010Q4 to 2012Q3, nine required a high school diploma or less. Only one (operating engineers & other construction equipment operators) required any sort of post-secondary education (see Table 2b).

During this eight-quarter period, Wyoming employers added 26,917 nonresident new hires with an average hourly wage of $13.00, compared to $12.32 for all new hires (see Table 2). The top occupations for nonresident new hires were maids & housekeeping cleaners (1,816); construction laborers (1,145); cooks, restaurant (1,115); truck drivers, heavy & tractor-trailer (999); and cashiers (998). Of the top 10 occupations for nonresident new hires, seven had an average hourly wage of less than $13.00. Those in the top 10 new hires accounted for 36.4% of all nonresident new hires.

Of the top 10 occupations for which Wyoming employers hire nonresidents, seven are the same occupations for which employers hire resident youths (see Tables 2b and 2c). This occupational overlap suggests that nonresidents out-compete resident youths to work as maids & housekeeping cleaners, restaurant cooks, cashiers, dishwashers, waiters & waitresses, food preparation & serving workers, and retail salespersons.

Nonresidents also compete for jobs with resident females, who are often hired for occupations such as maids & housekeeping cleaners, cashiers, waiters & waitresses, combined food preparation & serving workers, and retail salespersons. Each of these occupations was found in the top 10 for both resident female new hires and nonresident new hires with resident females making up more than half of all new hires in each of these occupations (see Figure 4). Are nonresidents being hired for these types of occupations because Wyoming employers have exhausted the resident female labor supply, or are employers hiring nonresidents instead of resident females?

Wyoming employers appear to be relying on nonresident workers more than ever before. As previously mentioned, nonresidents have historically been hired to work temporary seasonal jobs. However, employers are turning to nonresidents to fill other jobs that require more education and pay higher wages. Table 3 shows the top 10 occupations requiring more than a high school diploma for nonresident new hires. In four of these occupations, at least one in every five (20.0%) new hires was a nonresident: welders, cutters, solderers, & brazers (21.3%); crane & tower operators (28.4%); construction managers (43.1%); and surveying & mapping technicians (37.7%). Rounding up, operating engineers & other construction equipment operators fell into this category as well, with nonresidents accounting for 19.5% (705) of the 3,614 total new hires.

The occupations presented in Table 3 – specifically those marked with an asterisk – may represent training opportunities for Wyoming educators, training providers, and employers. Wyoming employers hired a significant proportion of these workers from outside of the state. This may indicate that Wyoming’s training providers and educators need to prepare more individuals to work in these types of jobs.

Conclusion and Future Research

The findings presented in this three-part series of articles point to an ongoing trend and were not unique to 2012. The research for these articles was conducted using Wage Records data through 2012. R&P recently published its latest Earnings in Wyoming by County, Industry, Age, and Gender, 2000-2013 (R&P, 2014), which includes data from 2013. The trends described in this series of articles continued in 2013: the number of resident youths working at any time continued to decline, and the number of nonresidents working at any time once again increased from previous year levels, even though the total number of persons working at any time in Wyoming declined from 2012 to 2013. The updated Earnings in Wyoming by County, Industry, Age, and Gender are available online at http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/earnings_tables/2014/index.htm.

R&P has also compiled four more quarters of new hires data since the research for these articles was done. Preliminary findings from the most recent new hires estimates – from 2011Q4 through 2013Q3 – are consistent with those presented in this article. Nine of the top 10 occupations for nonresident new hires were the same as those presented in Table 2b. The new hires estimates for 2011Q4 to 2013Q3 are being reviewed and will be available soon at http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/newhires.htm.

A forthcoming article will present other factors that have influenced the decline in resident youths participating in Wyoming’s labor force, including obtaining a Wyoming driver’s license and transportation. Although the resident youth population has remained relatively flat over the last decade, the number and proportion of youths who obtain a Wyoming driver’s license and participate in the labor force have declined substantially since 2008. An article will examine correlations of this decline, including economic changes, social trends, and the relationship between school and employment for youth.

References

Jones, S. (2002). Defining residency for the Wyoming workforce. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 39(11). Retrieved May 23, 2013, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/1102/a1.htm

Knapp, L. (2011). Survey captures data on Wyoming new hires. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 48(2). Retrieved March 5, 2014, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/0211/a2.htm

Knapp, L. (2013). What do Wyoming employers want? Evidence from the New Hires Survey. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 50(11). Retrieved March 24, 2014, from http://doe.state.wy.us/lmi/trends/1113/toc.htm

Leonard, D. (2010). Commuting and unemployment insurance claims: evidence from Natrona County. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 47(7). Retrieved September 3, 2013, from http://doe.state.wy.us/lmi/0710/a8.htm

Moore, M. (2013a). Youths and nonresidents in Wyoming’s labor force, part 1: How it works and why it matters. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 50(6). Retrieved September 3, 2013, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/trends/0613/a1.htm

Moore, M. (2013b). Youths and nonresidents in Wyoming’s labor force, part 2: Career paths and labor shortages. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 50(9). Retrieved March 24, 2014, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/trends/0913/a1.htm

Research & Planning (2014). Earnings in Wyoming by county, industry, age, and gender, 2000-2013. Retrieved March 25, 2014, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/earnings_tables/2014/index.htm