Youths and Nonresidents in Wyoming’s Labor Force, PART 2:

Career Paths and Labor Shortages

This article is the second in a three-part series that examines the trends of employed resident youths and nonresidents in Wyoming. The first article, published in the June 2013 issue of Wyoming Labor Force Trends, looked at employment trends among resident youths and nonresidents, and the potential consequences of young workers who lack exposure to employment opportunities and the dependence on a nonresident labor force (Moore, 2013). This article discusses the industries in which resident youths and nonresidents are employed, employment trends at the county level, and the effects that commuting may have on resident youth and nonresident employment.

In Wyoming, an individual’s place of residence and place of employment frequently are in different counties. Many Wyoming employers rely to some degree on workers who commute from another county, state, or in some cases country. Wyoming’s labor force is increasingly mobile, as the numbers of employed nonresidents and intercounty commuters have grown over the last two years (Research & Planning, 2013). During that time, employment has dropped among resident youths, who may not be as mobile as older workers. In this article, the term nonresidents is used to describe “individuals without a Wyoming-issued driver’s license or at least four quarters of work history in Wyoming” (Jones, 2002). The term resident youths in this article refers to those who are 19 and younger and possess a Wyoming driver’s license.

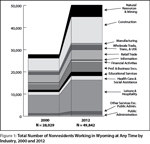

From 2000 to 2012, the total number of nonresidents employed in Wyoming at any time increased from 28,029 to 49,842 (21,813, or 77.8%; see Figure 1) and increased in each industry. The most significant percentage changes were found in natural resources & mining (207.5%) and construction (108.6%), two industries that “play a vital role in the progress of Wyoming’s economy” (Detweiler, 1998). Does such a reliance on out-of-state workers indicate a labor shortage in Wyoming? Are employers looking outside of the state because there are fewer bodies to fill these jobs, or because Wyoming’s younger workers have not been exposed to the proper job skills and work etiquette to fill these jobs? These types of questions will be addressed in part over a series of articles in Wyoming Labor Force Trends.

During this same period, the total number of resident youths employed at any time in Wyoming declined substantially, even though the population of youths ages 15-19 remained relatively flat (Moore, 2013). The number of employed resident youths decreased from 33,433 in 2000 to 20,991 in 2012 (-12,442, or -37.2%; see Figure 2).

Table 1 shows that the number of resident youths employed in Wyoming at any time decreased by double-digit percentages in each industry from 2000 to 2012. The largest decreases in resident youth employment were found in leisure & hospitality (-4,722, or -36.8%), retail trade (-2,522, or -36.8%), and construction (-1,145, or -47.5%).

Research & Planning (R&P) has studied the career paths of those who are employed in Wyoming as youths and continue to work in the state over the next 10 years. As youths, males and females tend to work primarily in the leisure & hospitality and retail trade sectors. As they grow older, females who continue to work in Wyoming tend to move into health care & social assistance and educational services, while males tend to move into construction and natural resources & mining (Glover, 2012). But if the starting point of a career path changes, does the destination change as well? If resident youths are unable to find work in Wyoming at a young age, do they have a positive view of Wyoming’s working environment, and will they be here as adults?

The decrease in the number of resident youths employed in Wyoming may be explained in part by an apparent decrease in the ratio of the youths who acquire a driver’s license, a trend that can be seen in Wyoming, surrounding states, and nationally. Research & Planning compared the U.S. Department of Transportation’s (DOT) Highway Statistics to the American Community Survey (ACS) Single-Year Estimates. A licensed driver rate was calculated by dividing the actual number of licensed drivers ages 16-19 by the total estimated population of 16- to 19-year-olds in Wyoming.

Assuming that the ACS Single-Year Estimates and the DOT’s Highway Statistics are accurate, the licensed driver rate of those ages 16-19 in Wyoming has steadily declined since 2000 (see Figure 3).

In 2000, for example, 86.5% (28,951) of the estimated 33,472 individuals ages 16-19 in Wyoming were licensed drivers. In 2010, 73.1% (22,678) of the estimated 31,028 individuals ages 16-19 in Wyoming were licensed drivers.

This may affect the data presented in this series of articles in several ways. For example, if a youth living and working in Wyoming does not possess a Wyoming driver’s license, he or she does not meet the definition of a resident youth as presented earlier in this article. In such a case, this person would be classified as a nonresident. Also, a decrease in the number of youths who possess a Wyoming driver’s license could mean a decrease in the number of youths who have access to transportation to and from work. This issue will be discussed in greater detail and by using other available data sets in forthcoming articles.

In some industries, nonresidents may be displacing resident youths, or filling the void created by the number of young workers who are not active in Wyoming’s labor force. For example, leisure & hospitality has historically employed the largest number of resident youths of all industries in Wyoming. From 2000 to 2012, total employment in this industry increased from 50,456 to 54,275 (3,819, or 7.6%). The loss of 4,722 resident youths (-36.8%) in leisure & hospitality was more than offset by the addition of 5,868 nonresidents (70.8%).

In other industries, employers turn to nonresidents when the economy expands rapidly and those employers have exhausted the local labor supply. As Table 1 shows, the largest percentage increase among employed nonresidents was found in natural resources & mining (207.5%), from 1,745 in 2000 to 5,366 in 2012. This is an industry that has not historically employed many workers under age 20. In 2012, for example, only 751 resident youths were employed at any time in natural resources & mining, less than 2.0% of the total employment in that industry. In the case of natural resources & mining, the increase in nonresident employment was driven more by economic expansion and not by the decline in resident youth employment.

Expansion and Downturn

Wyoming experienced substantial economic peaks and valleys from 2000 to 2012 (see Figure 4). During the middle of the decade, the state experienced rapid economic expansion. In each quarter of 2006, Wyoming’s average monthly employment increased by at least 3.9%, average monthly wages increased by 10.2% or more, and total wages increased by at least 14.8% from previous-year levels (QCEW, 2013). In first quarter 2009 (2009Q1), Wyoming entered an economic downturn, as average monthly employment, average monthly wage, and total wages all decreased from previous-year levels for five consecutive quarters.

During times of economic expansion, Wyoming employers often turn to nonresident workers after exhausting much of the resident labor supply (Leonard, 2010). This concept is illustrated in Figure 5, which shows a significant increase in the number of nonresidents employed in Wyoming at any time during the economic expansion. When the economy contracts, many nonresidents lose their jobs and often return to their home state. Since 2007, out-of-state claimants have accounted for at least 30.0% of all Unemployment Insurance (UI) benefit recipients (Moore, 2013).

This decrease in nonresident workers can be seen from 2009Q1 to 2010Q2 in Figure 5. Since then, the number of nonresidents employed at any time in Wyoming has nearly returned to pre-downturn levels. The employment level of resident youths remained relatively flat prior to and during the economic expansion. However, the number of resident youths employed at any time in Wyoming has decreased every year since 2008.

The average number of quarters worked by resident youths in any given year has remained stable since 2000. Table 2 shows the total number of persons working at any time in Wyoming and the average number of quarters worked for selected age groups. Even though the number of resident youths working at any time in Wyoming declined from 2000 to 2012, the average number of quarters worked was 2.5 to 2.6 for each year. In fact, the average number of quarters worked remained relatively stable for each age group and gender during this time. The 45-54 age group is included in this table because that age group had the highest average number of quarters worked from 2000 to 2012, between 3.5 and 3.6 for both males and females. The only significant increase can be seen among nonresidents, as the average number of quarters worked increased from 1.3 to 2.0 from 2000 to 2012. As Wyoming’s economy expanded from 2005 to 2008 and then contracted in 2009 and 2010, nonresidents appear to have been working for longer durations in the state than they did in the early 2000s. This information is available for all age groups at the industry and county levels at http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/earnings_tables/2013/index.html.

Where Do They Work?

Although the number of resident youths employed in Wyoming has decreased significantly from 2000 to 2012, two industries continue to employ the largest number of young workers: leisure & hospitality and retail trade. In both 2000 and 2012, more than half of all resident youths employed in Wyoming worked in one of these two industries (see Table 3). For example, of the 33,433 resident youths employed in Wyoming in 2000, 38.4% (12,838) were employed in leisure & hospitality. Even though the total number of employed resident youths declined to 20,991 in 2012, nearly the same proportion of resident youths worked in leisure & hospitality (38.7%, or 8,116).

The distribution of nonresidents employed in Wyoming at any time in 2012 was very similar to the distribution in 2000 (see Table 4). In both years, approximately half of all employed nonresidents worked in one of two industries: construction and leisure & hospitality. In 2000, 20.3% (5,693) of the 28,029 nonresidents employed in Wyoming worked in construction, while 29.6% (8,293) worked in leisure & hospitality. In 2012, 23.8% (11,876) of the 49,842 nonresidents employed in Wyoming at any time worked in construction, while 28.4% (14,161) worked in leisure & hospitality.

Nonresidents made up 9.0% of the 311,476 people working in Wyoming at any time in 2000, and 13.7% of the 362,596 people working at any time in 2012. Nonresidents accounted for a considerably larger percentage of total employment in 2012 than in 2000 in every industry but one (retail trade).

In 2000, the 8,293 nonresidents working in leisure & hospitality accounted for 16.4% of all workers in that industry. By 2012, the 14,161 nonresidents working in this industry made up 26.1% of all workers. During this time the presence of nonresidents also increased substantially in construction (16.6% in 2000 compared to 29.2% in 2012), natural resources & mining (7.1% in 2000 compared to 13.6% in 2012), and professional & business services (11.2% in 2000 compared to 16.7% in 2012). The proportion of nonresidents decreased only in retail trade (8.5% in 2000 compared to 5.3% in 2012), but the overall number of nonresident workers in this industry still increased.

The number of nonresidents employed in natural resources & mining also increased substantially, from 1,745 in 2000 to 5,366 in 2012 (207.5%). The number of nonresidents working in this industry was actually higher than in 2008, which was a peak year of employment in most industries. The increase in nonresident employment in Wyoming’s natural resources & mining industry may be tied in part to the increased activity in the Bakken Formation in Montana and North Dakota over the last two years. Anecdotal evidence suggests that Wyoming residents commuted to North Dakota for work during this time. R&P currently does not have a data-sharing agreement with North Dakota, so we are unable to determine how many Wyoming residents had wages in North Dakota during this time. Wyoming employers in natural resources & mining may have had to look outside of the state for workers in 2011 and 2012.

This is an example of the mobility that exists within the mining industry in Wyoming and its surrounding states. As noted by Wilson (2013), “advances in technology, increases in domestic demand and new land to explore have fueled the mining and gas exploration industries in several Western states, and job growth in a sector hit hard by the great recession has begun to surpass pre-recession levels.” As shown in Table 5, average monthly employment in Wyoming’s mining industry fell from 28,178 in first quarter 2012 (2012Q1) to 26,477 in first quarter 2013 (2013Q1), a decrease of -1,701, or -6.0% (Bullard, 2013). However, initial Unemployment Insurance (UI) claims did not increase accordingly. In January, February, and March 2013 (the three months that make up first quarter), the number of initial UI claims (890) increased just 11.4% from year-ago levels (799). In other words, even though employment in Wyoming’s mining industry decreased by 1,701, the number of initial UI claims increased by just 91. In each of the two previous quarters, when mining employment declined from year-ago levels, initial UI claims increased by 40.4% and 50.3%, respectively. This may indicate that those who left Wyoming’s mining industry in 2013Q1 didn’t lose their jobs, but rather moved on to another industry in Wyoming, or to work in the mining industry in a surrounding state.

Changes at the County Level

In Wyoming, county of residence and county of employment are often different from one another. An individual may reside in one county, and then travel to another for employment. As noted by Leonard, “in a mobile environment, labor markets do not respect county or state boundaries” (2010).

Each Wyoming county experienced a decrease in the number of employed resident youths and an increase in the number of employed nonresidents from 2000 to 2012 (see Table 6). The counties that experienced the greatest influx of nonresident workers were those that experienced the most growth overall. In Sublette County, for example, the number of employed nonresidents increased 591.4%, from 267 in 2000 to 1,846 in 2012. Total employment in Sublette County increased from 3,077 in 2000 to 7,929 in 2012 (4,852, or 157.7%). When a small county such as Sublette experiences such notable growth, employers must look outside of the county – and, in many cases, outside of the state – to fill jobs.

The increase in nonresident employment in Sublette County is illustrated in Figure 6, which was created using R&P’s commuting data. In first quarter 2005 (2005Q1), there were 903 people working in Sublette County from another county or another state. That number increased as Wyoming’s economy expanded through 2008, and then declined during the economic downturn that lasted from 2008Q4 to 2009Q4. However, as Wyoming’s economy has continued to recover over the last few years, the number of nonresidents working in Sublette County has again increased. In 2011Q3 – the most recent period for which commuting data are available – there were 1,887 nonresidents employed in Sublette County from another state, the largest number during any quarter since 2000. As Figure 6 shows, the top five states for nonresident workers in Sublette County in 2011Q3 were Idaho (289), California (264), Texas (159), Utah (154), and Colorado (101).

The mobile nature of Wyoming’s job market may be detrimental to resident youths who are seeking employment. While older workers may commute from one county to another to work, younger workers may not be so mobile. Younger workers may be tied to their county of residence by a variety of factors that do not restrict older workers, such as school attendance or the lack of reliable transportation or a driver’s license.

The number of employed resident youths declined 35.0% to 45.0% from 2000 to 2012 in most counties (see Table 6). The most significant percentage decreases were seen in Teton (-54.8%, or -926) and Carbon (-50.3%, or -492) counties. Natrona County, which had the second highest employment number of resident youths across all counties in 2012, experienced a relatively smaller percentage decrease in resident youth employment from 2000 (-24.6%, or -1,044). By comparison, resident youth employment was highest in Laramie County in 2012, but declined 30.5% (-1,389) from 2000.

Interstate, intercounty, and intracounty commuting data for Wyoming are available at http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/commute.htm.

Conclusion

Wyoming’s labor market is not defined by geographic boundaries. Wyoming workers often travel from one county to another for employment, and Wyoming employers turn to nonresident workers to fill jobs during times of economic expansion. This article showed the demographic change in Wyoming’s workforce since 2000, as more nonresidents and fewer resident youths are working. The third and final article in this series will be published in a forthcoming issue of Wyoming Labor Force Trends, and will focus on the types of jobs that resident youths and nonresidents are hired to work in Wyoming, the skills that those jobs require, how much they pay, and what types of benefits they offer.

References

Bullard, D. (2013). Local jobs and payroll in Wyoming: Job growth remains weak in first quarter 2013. Retrieved November 25, 2013, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/qcewnews.htm

Detweiler, G., and Yu, X. (1998). Wyoming mining industry: an in-depth analysis. Wyoming Labor Force Trends 35(4). Retrieved September 13, 2013, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/0498/0498a2.htm

Glover, T. (2012). A decade later: Tracking Wyoming’s youth into the labor force. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 49(3). Retrieved November 22, 2013, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/trends/0312/a1.htm

Jones, S. (2002). Defining residency for the Wyoming workforce. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 39(11). Retrieved May 23, 2013, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/1102/a1.htm

Leonard, D. (2010). Commuting and unemployment insurance claims: Evidence from Natrona County. Wyoming Labor Force Trends 47(7). Retrieved September 3, 2013, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/0710/a8.htm

Moore, M. (2013). Youths and nonresidents in Wyoming’s labor force, part 1: How it works and why it matters. Wyoming Labor Force Trends 50(6). Retrieved September 3, 2013, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/trends/0613/a1.htm

Research & Planning. (2013). Earnings in Wyoming by Industry, Age, & Gender, 2000-2012. Retrieved December 5, 2013, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/earnings_tables/2013/index.html. Commuting in Wyoming, 2005Q1 to 2011Q3. Retrieved December 5, 2013, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/commute.htm

U.S. Census Bureau. (2013). American Community Survey Single Year Population Estimates. Retrieved November 25, 2013, from http://www.census.gov/acs/www/

U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. (2013). Highway Statistics Series, 2000-2012. Retrieved November 25, 2013, from http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policyinformation/statistics.cfm