Evaluating the Wyoming Unemployment Insurance System and Comparing it with the U.S. Average and Neighboring States

Wyoming’s Unemployment Insurance (UI) system has functioned well, especially during the Great Recession, in terms of efficiency and effectiveness, achieving the goals of maintaining solvency across the business cycle, providing dependable UI benefits, and distributing cost sharing fairly among all industries. The UI Trust Fund stayed solvent. Wyoming paid the second highest average weekly UI benefit amount to unemployed workers and had the highest wage replacement rate (45.3%) when compared to neighboring states in 2009, the worst year of the recession in Wyoming. UI costs to employers were ranked middle to high compared with other states, but were more evenly and proportionally shared among low paying and high paying industries.

Unemployment Insurance (UI) benefits in the United States have been a major temporary financial support to millions of unemployed workers each year, especially during the Great Recession (NBER, 2010) and for a few years after. The Great Recession also has challenged each state’s UI trust fund solvency, UI benefit sufficiency to unemployed workers, and UI cost to employers. Unemployment Insurance is a federal and state cooperative program, but each state has its own regulations and UI laws that can greatly affect its UI system performance.

This article examines some of the UI statistics for Wyoming and neighboring states and compares their UI systems’ capacity and performance.

There may be many different ways to evaluate a UI system’s efficiency (W.E. Upjohn Institute), but for the purposes of this article, efficiency and effectiveness mean the achievement of solvency across the business cycle, providing a dependable UI benefit at the most needed time, and limiting costs while sharing costs evenly and proportionally across all industries.

UI Trust Fund Solvency

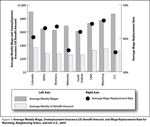

Wyoming was one of 17 states that did not have to borrow money from the federal UI program to pay UI benefits during and after the Great Recession (E.M. Dullaghan, 2013). Most states had to take millions or billions of dollars in loans to pay regular UI benefits. To judge whether a UI system functions well, the first and most straightforward way is to see if it has sufficient funds to pay benefits at the most needed time periods – economic downturns – without borrowing money, increasing taxes on already struggling employers, or reducing benefits to unemployed workers. An efficient UI system should be able to build up its UI trust fund during periods of economic growth. In some states, laws link UI statutory definitions such as taxable wage base or tax rate directly to the most recent years’ wage or benefit charges, and are adjusted automatically to reflect current economic conditions (growth or decline) for a reasonable period. Some states require legislative approval for adjustments to UI components. In Wyoming, most UI components are linked to recent economic conditions directly through UI law. Its taxable wage base is set to 55% of the previous calendar year’s average state UI covered salary, and its base tax rate is set as the result of the past three fiscal years’ benefits charged to the employer, divided by the employer’s total taxable wages over the same period. As Figure 1 shows, Wyoming employers paid lower UI tax rates on both total wages and taxable wages during the past two economic downturn periods (2002 to 2003 and 2008 to 2009; Wen, 2011), and paid higher rates during the recovering or growing years.

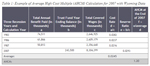

One of the most commonly used measures of UI Trust Fund solvency is average high cost multiple (AHCM and National Employment Law Project, 2013), which is the reserve ratio (the UI trust fund balance divided by total UI covered wages) divided by average cost rate of three high-cost years that include either three recessions or at least 20 years’ history. The cost rate is the benefits paid in the year divided by the total covered wages in the same year. Table 1 shows a detailed example on the calculation of AHCM. The Advisory Council on Unemployment Compensation recommends an AHCM at 1.0 as a safe level, which means that if a future recession is the average magnitude of the past three recessions, the state would be able to pay one year of UI benefits with the current reserved trust fund alone. Figure 2 shows that of the six neighboring states and Wyoming, three (Colorado, Idaho, and South Dakota) had a pre-recession AHCM under 1.0 in 2007 (ET Financial Data Handbook 394 Report). Those three states’ UI trust funds proved insufficient during the Great Recession, forcing those states to borrow money from the Federal UI fund. In contrast, Utah with an AHCM at 1.47, Montana with 1.45, Wyoming with 1.20, and Nebraska with 1.19, did not need to borrow money to pay UI benefits.

UI Benefits to Unemployed Workers and Wage Replacement Rate

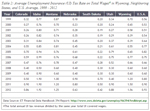

Millions of unemployed workers in the U.S. relied on UI benefits as a temporary financial bridge during a difficult time. How much a UI system is able to provide to the unemployed workers, how long it is able to support them during their time of need, and how high the wage replacement rate state UI benefits could reach are other important criteria to evaluate a UI system’s performance. The higher UI benefits an unemployed worker could receive, the easier for her family and her to survive difficult times. In Wyoming, 2009 was the worst year affected by the Great Recession, which had the largest annual number of unemployed workers collecting UI benefits since 1997, the first year for which comparable data are available (Wen 2013). Wyoming’s UI system in 2009 paid an average weekly benefit amount (AWBA) of $347.40 to a total of 37,251 persons claiming unemployment benefits. This AWBA was the second highest among neighboring states and higher than the U.S. average in 2009 (see Figure 3). Colorado paid the highest AWBA ($360.96), and Nebraska paid the lowest ($249.45).

Compared to neighboring states, Wyoming’s UI benefit in 2009 provided the highest wage replacement rate, 45.3%. Nationally, on average, UI benefits only replaced 35.8% of the average weekly wage (AWW). Utah was the second highest state in terms of wage replacement rate (44.3%), and Nebraska had the lowest replacement rate (36.4%). The higher the AWW a state had, the more difficulty its UI system had in replacing it at a higher rate level. Figure 3 shows that in 2009, Colorado paid the highest AWW ($895.15), and South Dakota paid the lowest ($606.29). To reach a wage replacement rate of 45%, South Dakota’s UI system would have needed to pay an AWBA of only $272.83, while Colorado would have had to pay $402.82 (47.6% more than South Dakota) to reach the same wage replacement rate. Wyoming’s employers paid an average weekly wage of $766.93 in 2009, ranked as the second highest among neighboring states. Its highest wage replacement rate (45.3%) among neighboring states on a relatively higher (second highest) AWW indicates that Wyoming’s UI system functioned well and was more dependable for its unemployed workers than UI systems in other states during this critical period.

UI Cost to State Employers

Cost is another important component when evaluating a UI system. UI taxes are based on employees’ wage levels, and employers are responsible for paying the UI tax. There are two kinds of UI costs to each UI covered employer:

Federal UI Tax Act (FUTA) taxes are collected by the Internal Revenue Service to “cover the costs of administering the UI and Job Service programs in all states. FUTA pays one-half of the cost of extended unemployment benefits (during periods of high unemployment) and provides for a fund from which states may borrow, if necessary, to pay benefits” (United States Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration);

State UI taxes are collected by state UI tax divisions and used to pay benefits to unemployed workers. This report focuses only on state UI taxes because they vary from state to state depending on each state’s UI laws.

As mentioned earlier, most of Wyoming’s UI components such as the UI tax rate, taxable wage base, and maximum weekly UI benefit amount are defined by state law and directly linked to (as a percentage of) the most recent state economic statistics, such as total UI covered wages, taxable wages, and UI benefits paid, and are adjusted automatically. For example, the taxable wage base is defined as 55 percent of the previous year’s state average annual wage and rounded down to the nearest one hundred dollars (W.S.). Wyoming’s taxable wage base in 2011 was $22,300, down from $22,800 in 2010 (a 2.2% decrease), due to the decrease in the average UI covered annual salary from $41,484 in 2008 to $40,704 in 2009. The UI tax rates displayed in Figure 1 show that Wyoming’s UI system collected less UI taxes during the state economic downturns (2002–2003 and 2008–2009), which were the most financially difficult years for state employers, and then collected more UI taxes during subsequent recovering and growing years. This is evidence of a properly functioning UI system in terms of timing and changing UI tax rates.

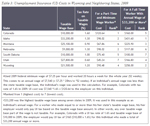

There are different ways to look at UI costs across states. The average UI tax rate on total wages, which is the annual UI tax revenues divided by total annual UI covered wages, may be the most straightforward way to interpret the average UI cost. Each dollar of wages that employers pay employees determines how much they need to pay for UI tax. In 2009, Wyoming’s employers paid an average of 60 cents in UI taxes for every $100 they paid in wages to their employees (see Table 2). This 0.60% tax rate was the same level as the U.S. average and Montana’s rate. Idaho’s employers paid the highest rate, 90 cents for every $100 of wages. South Dakota and Utah employers paid the lowest rates, 30 cents.

The average UI tax rate on taxable wages, which is the annual UI tax revenue divided by the annual total taxable wages, can be used to compare in greater detail average UI costs in Wyoming and neighboring states. UI tax is limited by the taxable wage base, and wages exceeding that base are not taxable. Both average UI tax rate and taxable wage base change every year for many states and differ greatly between states. A higher tax rate does not always mean more UI taxes if the taxable wage base is small or decreased over the year. As a result, for a fair comparison on UI cost across the states, neither of these two terms should be used independently. Table 3 shows how these two UI components could affect the actual UI cost to employers under different wage levels. In 2009, Colorado had the highest taxable wage tax rate (1.6%) but the second lowest taxable wage base ($10,000) among seven states, with Nebraska having the lowest taxable wage base ($9,000). Two wage levels are used in this example: a low paying position and a high paying position. For the low paying position in Colorado, we assume that the individual only worked 20 hours a week at the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour, so this individual’s annual income would be $7,540 (or, $7.25 x 20hrs/week x 52 weeks). The UI cost to the employer for this individual would be $120.64 ($7,540 * 1.6%) for the year, ranked as the highest among the related states. The same individual in Utah would only cost the employer about one-third of that ($45.24 a year) on UI tax, the lowest. However, it could be a totally different story for the high paying position. In this example assume that an individual made an annual wage of $33,200 or more in 2009. This wage level was also Idaho’s taxable wage base for that year, the highest among Wyoming and its six neighboring states. The employer’s UI cost in Colorado for this highly paid individual would be only $160.00 (= $10,000 * 1.6%, taxable wage base times tax rate), the third lowest among the states. However, for the same individual, employers in Idaho would pay $431.60 on UI tax, nearly three times more than a Colorado employer, highest among the states in the comparison. South Dakota employers would pay the lowest UI tax, only $100.00. This indicates that a UI system such as Colorado’s, with a low taxable wage base, had a UI tax revenue that was more dependent on low paying positions or industries than high paying ones; high paying industries did not share a proportionally equivalent burden of the UI cost, even though high paying positions usually receive more UI benefits than low paying positions. As a result, a state UI trust fund may carry a higher risk than other states’ UI trust funds due to the uneven distribution of the cost among industries and the dependence on those jobs. In these examples, Wyoming’s UI cost would be $90.48 for the low paying job (ranked the fourth among states) and $258 for the high paying job (the second highest). Wyoming’s UI costs were more evenly distributed among low paying and high paying industries.

Summary

Wyoming’s UI system has functioned very well, especially during the Great Recession. The UI Trust Fund stayed solvent, unlike the majority of other states in the nation that had to borrow money from the Federal program to pay the regular UI benefits to unemployed workers. In comparison to neighboring states in 2009, Wyoming paid the second highest average weekly UI benefit amount to unemployed workers and held the best wage replacement rate. The UI cost to employers was ranked middle to high compared with other states but the cost was more evenly shared among low paying and high paying industries.

References

E. M. Dullaghan. (2013). E-mail contact with economist, November 13, 2013. U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration.

Economic Policy Journal. (2010, May). Retrieved from http://www.economicpolicyjournal.com/2010/05/32-states-have-borrowed-from-treasury.html

National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). (2010). Retrieved September 19, 2012, from http://www.nber.org/cycles/sept2010.html

National Employment Law Project. (2010, April). Understanding the Unemployment Trust Fund Crisis of 2010. Unemployment Insurance Briefing Paper. Retrieved from http://www.nelp.org/page/-/UI/solvencyupdate2010.pdf?nocdn=1

U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration. ET Financial Data Handbook 394 Report. Retrieved from http://www.ows.doleta.gov/unemploy/hb394/hndbkrpt.asp

United States Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration (2014). Unemployment Insurance Tax Topic, extracted on January 3, 2014 at http://www.workforcesecurity.doleta.gov/unemploy/uitaxtopic.asp

Wen, S. (2011, November). An overview of Wyoming’s unemployment insurance trust fund and trust fund liability. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 48(11).

Wen, S. (2013, May). Wyoming unemployment insurance benefit expenses and number of recipients decline in 2012. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 50(5).

W.E. Upjohn Institute. (n.d.). Unemployment Insurance. Retrieved January 27, 2014, from http://www.upjohninst.org/Research/UnemploymentDisabilityandPoverty/UnemploymentInsurance

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Average_high_cost_multiple

Wyoming Employment Security Law, Wyo. Stat. §§ 27-3-102.