How it Works and Why it Matters

Wyoming employers have historically relied upon resident youths and nonresident workers to some degree, often to fill low-paying, seasonal jobs. Since 2000, the number of employed resident youths has decreased, and the number of employed nonresidents has increased. Are nonresidents displacing resident youths in Wyoming's workforce, or are Wyoming employers turning to nonresidents after exhausting the supply of resident youths? What potential consequences do these trends bring? This three-part series of articles addresses those questions by presenting definitions of resident youth workers and nonresident workers and examining the changing roles of those segments of the workforce.

Potential Consequences

- Youths

- Lack soft skills

- Have no experience with work routine

- Don't know how to balance work and school responsibilities

- Nonresidents

- Don't invest in communities where they work

- Raise regional recruiting expenses

- Have little access to health insurance benefits

In order to analyze the demographics of Wyoming's workforce, the Research & Planning (R&P) section of the Wyoming Department of Workforce Services collects demographic data from a variety of sources, including Wyoming driver's license files through an agreement with the Wyoming Department of Transportation (WYDOT). Because Wyoming imports much of its labor from other states, many workers do not possess a Wyoming driver's license and demographic data are not available. These workers are referred to in this article as nonresidents. In 2002, R&P defined nonresidents as "individuals without a Wyoming-issued driver's license or at least four quarters of work history in Wyoming" (Jones, 2002). Some of these nonresidents may eventually establish residency and obtain a driver's license; in that case, demographics for those workers become available when the driver's license file is updated the following year. R&P is able to identify the demographics for employed resident youths. The term resident youths in this article refers to those 19 and younger who possess a Wyoming driver's license.

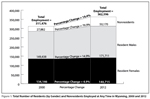

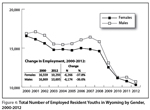

Since 2000, nonresident workers have made up a larger percentage of Wyoming's workforce (Jones, 2006). From 2000 to 2012, the number of employed nonresidents grew at a higher rate than the number of employed Wyoming residents. As illustrated in Figure 1, the total number of persons employed in Wyoming increased from 311,476 in 2000 to 362,596 in 2012 (51,120, or 16.4%). During that time, the number of employed nonresidents increased from 27,882 to 50,170 (22,288, or 79.9%). The number of employed resident males increased from 149,438 to 171,711 (22,273, or 14.9%) while the number of employed resident females increased from 134,146 to 140,715 (6,569, or 4.9%).

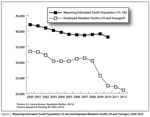

During times of economic expansion, Wyoming employers often turn to nonresident workers after exhausting much of the resident labor supply (Leonard, 2010). From 2005 to 2008, the number of employed nonresidents increased significantly, from 33,085 in 2005 to 51,930 in 2008 (57.0%; see Table 1). When the state's economy contracts – as was the case from fourth quarter 2008 (2008Q4) to fourth quarter 2009 (2009Q4) – many nonresidents lose their jobs and often return to their home state. From 2008 to 2009, the total number of persons working at any time in Wyoming decreased from 383,471 to 368,186 (-15,285, or -4.0%). During that economic downturn, the number of employed residents decreased from 331,541 to 325,947 (-1.7%) while the number of employed nonresidents decreased at a much greater rate from 51,930 to 42,239 (-9,691, or -18.7%).

As Wyoming continues to recover from the economic downturn over the last two years, the number of nonresidents employed in the state has again increased. The total number of persons working at any time in Wyoming increased from 359,724 in 2011 to 362,596 in 2012 (2,872, or 0.8%). However, total employment increased only because the number of nonresidents employed in Wyoming increased substantially during this time. The number of nonresidents employed in Wyoming at any time increased from 41,052 in 2011 to 50,170 in 2012 (9,118, or 22.2%), while the total number of employed residents decreased from 318,672 in 2011 to 312,426 in 2012 (-6,246, or -2.0%). This decline in employed residents was even greater numerically and percentagewise than the decline during the state's economic downturn from 2008 to 2009, when the number of employed residents dropped from 331,541 to 325,947 (-5,594, or -1.7%).

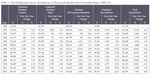

The increasing number of nonresidents in Wyoming's workforce is associated with a declining number of resident youths employed in the state. During the economic downturn from 2008Q4 to 2009Q4, younger workers were more likely to be affected by job loss than other age groups (Harris, 2013). By the end of 2012, a significant number of those young workers who had lost their jobs had yet to return to the workforce. The number of employed resident youths in Wyoming decreased from 33,433 in 2000 to 20,991 in 2012 (-12,442, or -37.2%). During this time, however, Wyoming's teenage population remained relatively flat (see Figure 2). Possible reasons for the decrease in employed resident youths are discussed later in this article.

Figure 3 shows that employed resident youths and employed nonresidents trended in opposite directions from 2000 to 2012. The number of employed resident youths was relatively flat from 2000 to 2007 and has been on a downward trend since 2008. From 2000 to 2007, the number of employed resident youths decreased from 33,433 to 31,285 (-2,148, or -6.4%). From 2008 to 2012, the number of employed resident youths dropped from 30,450 to 20,991 (-9,459, or -31.1%).

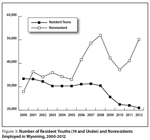

As shown in Figure 4, gender is not a factor in the decline of employed resident youths. Employed resident female youths decreased from 16,559 in 2000 to 10,293 in 2012 (-37.8%), while employed resident male youths decreased from 16,869 to 10,695 (-36.6%).

Where Have the Youths Gone?

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) publishes annual labor force estimates from the Current Population Survey (CPS). The estimates presented in the CPS are estimates of population and employment by place of residence based on a sample of households, as opposed to the previously mentioned employment levels, which are an actual count of persons receiving wages in Wyoming at any time during the year by place of work. CPS estimates show that from 2003 to 2012, Wyoming's population of youths age 16-19 decreased from an estimated 32,000 to an estimated 27,000 (-5,000, or -15.6%; BLS, 2013). During that time, the number of youths age 16-19 employed in Wyoming decreased from an estimated annual average of 19,000 to an estimated 14,000 (-5,000, or -26.3%). BLS estimates differ from the actual employment numbers captured in R&P's Wage Records database, but both datasets indicate that fewer young Wyoming workers were employed in 2012 than in previous years, while the overall teen population has remained relatively constant.

Wyoming's downward trend of employed youths is consistent with the downward trend of employed youths across the U.S. CPS estimates show that the U.S. population of youths age 16-19 increased from 16.1 million in 2003 to 17.0 million (888,000, or 5.5%) in 2012 (BLS, 2013). However, the number of employed youths age 16-19 in the U.S. decreased from 5.9 million in 2003 to 4.4 million in 2012 (-1.5 million, or -25.2%).

There are several factors contributing to the decline of younger workers, including "a labor market weakened by recessions, a diminishing number of federal funded summer jobs, and competition from other groups for entry-level job opportunities" (Morisi, 2010). In Wyoming, youths may be competing for jobs with nonresident workers and older workers.

In addition, social attitudes about youth employment may have changed over the last decade. While many parents previously expected youths to hold jobs, more parents today may want their children to focus on education instead. Youths and their parents may also view the low wages paid to marginal jobs as an inefficient way to pay increasing tuition costs. According to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), the annual cost of undergraduate tuition, room, and board at public institutions increased 41.6% from $9,390 during the 2000-01 school year to $13,297 during the 2010-11 school year (NCES, 2012). In Wyoming, the average UI covered wage for employed resident youths 19 and younger increased from $3,369 in 2000 to $5,099 in 2012. More youths may be relying on financial assistance, such as the Federal Pell Grant Program and Wyoming's Hathaway Scholarship Program, to pay for college.

Why has the number of employed youths declined so dramatically? What are they doing instead of working? Do scholarship programs play a role in the decline of resident youth workers? R&P recently received a Wyoming Data Quality Initiative grant that will make it possible to track students from school into the labor force longitudinally and answer some of these questions. This will be a major area of study for R&P over the next few years.

Consequences of These Trends

Camarota stated that, "Holding a job instills the habits and values in teenagers during their formative years that are helpful in finding or retaining gainful employment later in life" (December 2011). Effects of the decline in employed resident youths are being felt now by Wyoming employers and higher learning institutions. Those who are employed as teenagers learn soft skills on the job; these are defined by the U.S. Department of Labor as "workforce readiness skills" and include communication, enthusiasm and attitude, teamwork, networking, problem solving and critical thinking, and professionalism (U.S. DOL, n.d.). Those who are not employed as youths may struggle with following directions, showing up on time and working an entire shift, communicating with customers and co-workers, and balancing work responsibilities with other commitments. Through survey responses and customer contacts, R&P has found anecdotal evidence to support these theories about the lack of soft skills in Wyoming's younger workers.

In addition, Wyoming faces several challenges because of the state's reliance on a nonresident labor force, such as high Unemployment Insurance (UI) benefit payouts, charity health care costs, and housing shortages. Employers are faced with higher recruiting and housing costs, and are reliant on nonresident workers who may not be available as their home states' economies improve.

Jones stated that, "people who do not obtain a driver's license in a given state are less attached to that state than those who do" (2002). Nonresidents who live in temporary housing are less likely to invest in the communities in which they work. They may take their earnings back to their home county or state and spend money there, not in the community in which they work. And what happens to a community when it is populated with people who do not live there? What kind of a commitment does a nonresident make to a community in which he or she works, but does not live?

When the jobs go away, nonresidents who are not attached to the state often leave. Because of this, out-of-state claimants have historically accounted for a significant portion of all UI benefit recipients (Leonard, 2010). While nonresident status is determined using the WYDOT driver's license file and other administrative databases, out-of-state workers are deemed as such by the address on their UI claim file.

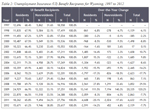

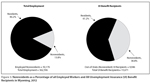

During each year since 2000, approximately one in 10 persons employed in Wyoming (between 9.0% and 13.8%) was a nonresident. By comparison, approximately one in three UI benefit recipients (between 27.9% and 38.8%) during that time was an out-of-state claimant (see Table 2). In 2012, nonresidents accounted for 13.8% of all employed workers and out-of-state claimants accounted for 38.8% of all UI benefit recipients (see Figure 5).

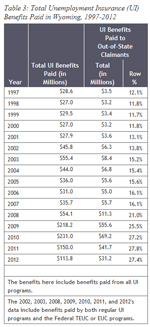

In 1997 – the first year for which comparable UI claims data are available – Wyoming paid $3.5 million to out-of-state claimants, or 12.1% of the $28.6 million total. As shown in Table 3, since Wyoming's economic downturn in 2009, approximately one-fourth of all UI benefits have been paid to out-of-state claimants. In 2010, Wyoming paid $69.2 million to out-of-state claimants, or 27.2% of the $231.0 million total. By 2012 the amount paid to out-of-state claimants had dropped by nearly half ($31.2 million) but still accounted for 27.4% of the $113.8 million total.

Health care costs and charity care are other concerns for communities that rely on nonresident workers. R&P's New Hires Job Skills Survey asks employers about several benefits offered to newly hired workers, one of which is health insurance. (More information on the New Hires Job Skills Survey is available at http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/newhires.htm). In 2012, new hires who were Wyoming residents were offered health insurance at a greater rate than nonresidents. Of the 93,715 resident new hires in 2012, 33,113 (35.3%) were offered health insurance. Of the 17,187 nonresident new hires, 4,703 (27.4%) were offered health insurance. This will be discussed in greater detail in the third article in this three-part series.

As mentioned earlier, nonresidents are often hired to fill part-time or seasonal jobs, and a very low percentage of part-time jobs in Wyoming have historically been offered access to benefits (Manning and Saulcy, 2013). So what happens when a nonresident working in Wyoming without health insurance requires medical care, especially for a catastrophic event? According to Fladiger (2013), Wyoming Medical Center in Casper provided $22.5 million in indigent care for Natrona County residents and $8.1 million in indigent care for non-county residents in 2012. When nonresidents who lack health insurance and work low-paying jobs require health care, someone else pays the bill.

Another challenge associated with a nonresident labor force is the potential for a housing shortage and inflated housing costs. When Wyoming's economy expanded rapidly from 2005 to 2008, many of the state's smaller counties experienced an influx of nonresident workers. In Sublette County, for example, the number of nonresident workers increased from 263 in 2000 to 1,469 in 2008 (458.6%). New workers moved in much faster than housing could be built. The increased demand and short supply drove up housing costs in Sublette County during this time, as the average home sale price increased from $142,338 in 2000 to $309,167 in 2007 (Sublette County, n.d.).

Conclusion

The proportion of resident youths and nonresidents in Wyoming's labor force has changed over the last 12 years. Fewer resident youths are working now than at any time since 2000. As Wyoming employers have looked to fill marginal jobs – those that are low-paying and often seasonal – they have turned to nonresidents. In some instances, this appears to be the result of Wyoming employers exhausting much of the resident youth labor force. When Wyoming's southwest region experienced rapid economic growth from 2005 to 2008, there simply weren't enough residents to fill the jobs created by the expanding economy.

In recent years, it appears that the shift in resident youths and nonresidents is the result of fewer youth successfully participating in Wyoming's employment opportunities. Wyoming is not unique in this regard. Youth employment is down across the U.S., even though the overall teenage population has remained relatively steady and even increased in some areas. There are several possible reasons for this change: a shift in cultural views of youth employment versus education, older workers and migrant workers competing for jobs once held by youths, more sources for assistance for college, and fewer summer jobs have all been noted as potential factors in declining youth employment.

By linking new educational databases to existing databases, R&P will be able to address several important questions: Are fewer youths working so that they can concentrate on schooling and receive scholarship funding to continue their education? Once they complete their postsecondary education, are young people staying in Wyoming to work, or are they leaving the state to pursue employment elsewhere?

Nonresident workers have historically been a significant part of Wyoming's workforce, especially since 2000. Over the last two years, as the state has continued to recover from the recent economic downturn, Wyoming employers are relying on nonresident workers more than ever before. Total employment increased due to the significant growth of employed nonresidents, as more than 9,000 employed nonresidents offset the decrease of 6,000 resident workers from 2011 to 2012. Nonresidents are employed for longer periods than ever before and are earning significantly more on an average annual basis. Did these nonresidents establish residency and obtain a Wyoming driver's license in 2013, or did they leave Wyoming after a brief period of employment? R&P will be able to examine these questions in 2014, when the driver's license file is updated.

The second article in this three-part series will be published in the August 2013 issue of Wyoming Labor Force Trends.

Research Analyst Michael Moore can be reached at michael.moore@wyo.gov.

References

Camarota, S. (2011, December). Declining summer employment among American youths. Center for Immigration Studies. Retrieved July 16, 2013, from http://www.cis.org/declining-summer-employment

Fladiger, G. (2012, October 12). WMC reports lower charity costs to commission. Casper Journal. Retrieved June 19, 2013, from http://tinyurl.com/qg2bms7

Harris, P. (2013). Demographics of UI claimants: More males continue to receive benefits than females. Wyoming Labor Force Trends 50(5). Retrieved May 23, 2013, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/trends/0513/a2.htm

Jones, S. (2002). Defining residency for the Wyoming workforce. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 39(11). Retrieved May 23, 2013, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/1102/a1.htm

Jones, S. (2006). States of origin for Wyoming workers. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 43(4). Retrieved May 23, 2013, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/0406/a1.htm

Leonard, D. (2010). Tracking workers' re-employment after job loss. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 47(11). Retrieved May 23, 2013, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/1110/a1.htm

Manning, P., and Saulcy, S. (2013). Wyoming Benefits Survey 2012. Retrieved June 20, 2013, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/benefits2012/index.htm

Morisi, T. (2010). The early 2000s: A period of declining teen summer employment rates. Monthly Labor Review, May 2010. Retrieved May 23, 2013, from http:// www.bls.gov/opub/MLR/2010/05/art2full.pdf

National Center for Education Statistics. (2012). Fast facts: Tuition costs of colleges and universities. Retrieved June 20, 2013, from http://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=76

Sublette County. (n.d.) Socioeconomics/housing. Retrieved June 19, 2013, from http://www.sublettewyo.com/DocumentCenter/Home/View/384

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2013). Employment status of the civilian noninstitutional population by state. Retrieved June 7, 2013, from http://stats.bls.gov/lau/#tables

U.S. Department of Labor, Office of Disability Employment Policy. (n.d.). Skills to pay the bills: Mastering soft skills for workplace success. Retrieved June 24, 2013, from http://www.dol.gov/odep/topics/youth/softskills/