What Do Employers Want? Part 2: Evidence from the New Hires Survey for Health Care

Wyoming’s health care & social assistance and educational services industries share several traits. Both industries deal with a large client base on a daily basis, and both industries employ larger proportions of females than all industries as a whole. In addition, wages tend to be higher in both the health care and education industries than the statewide average.

Much of the research conducted by the the Research & Planning (R&P) section of the Wyoming Department of Workforce Services relies on data retrieved from secondary administrative data sources such as the state’s unemployment insurance wage records database, the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) files (UI employment tax files), and a variety of occupation and motor vehicle licensing files. These data sets contain a wealth of information that allow R&P to conduct in-depth economic analyses without burdening employers or workers with too many requests for data. For more information about how wage records and other administrative data sets are used by R&P, please see http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/w_r_research/toc.htm#W.

Occasionally, these administrative records do not contain crucial elements of information that only employer surveys can provide. In the case of the Department of Workforce Services Job Skills Survey, also known as the New Hires Survey, a combination of wage records, QCEW data, and driver’s license files can show how many jobs were filled during a particular time frame, what industries these jobs were found in, the age and gender of workers filling the jobs, and the job tenure or turnover, but not specifics such as benefits offered at the point of hire, occupation, or necessary skills needed to perform the job’s duties. Since fourth quarter 2009 (2009Q4), R&P has conducted the New Hires Survey on a quarterly basis. This survey was designed to capture occupation, benefits, wages, full-or part-time employment status, usual hours worked, education and licensing requirements, and job skills for Wyoming jobs.

New hires are defined as workers who had not previously worked for a particular employer since 1992, the first year for which wage records are available for analyses (Knapp, 2011). The New Hires Survey helps identify what jobs are being filled across the state.

This article provides a comparison of new hires working in the education and health care industries. These two industries were chosen in part because R&P has conducted several studies on them in the past. In 2008 and 2009, R&P conducted several large-scale analyses of nurses in Wyoming using both administrative datasets and surveys (Cowan, Jones, Knapp, Leonard & Saulcy, 2008; Harris, Jones, Knapp, & Leonard, 2008; Jones, 2009). These studies are available at http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/nursing.htm. In 2012 and 2013, R&P conducted two large-scale analyses of teachers and teacher wages in Wyoming and surrounding states using administrative datasets and other publicly accessible secondary data sources (Gallagher, et al., 2012; Gallagher, et al., 2013). These studies are available at http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/education_costs.htm. An analysis of new hire jobs in each of these industries adds another dimension to R&P’s research.

The first article in this series, “What do Wyoming employers want? Evidence from the new hires survey” (Knapp, 2013), noted that one of the purposes of this survey is to provide labor market information about potential jobs to education and training providers, job seekers, and employers. That article focused only on characteristics of occupations across all industries combined. By focusing on characteristics of jobs in two specific industries, the results of this article should better illustrate the usefulness of these data at the industry level. The conclusions section of this analysis will include two detailed examples of how these data can be combined for use by a variety of customers.

Methodology

A random sample of new hires, chosen to statistically represent each of the 20 industries of the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS), is drawn each quarter from employers in the private sector and in local government. A questionnaire is mailed to each new hire’s employer along with an explanatory cover letter that provides an overview about the purpose of the survey. The cover letter explains that the survey is designed to collect information about job skills needed by the workforce that will help educators develop curriculums that will in turn help employers access a more skilled labor force in the future. As noted, however, the results of this study benefit a much larger audience than just educators and training providers. The questionnaire identifies the reference date, or time frame of interest, which is generally six months prior to the first mailing of the survey instrument, and a selection of questions that, with the exception of one that asks employers to rate their satisfaction with the employee’s job skills, refer to the job filled by the employee rather than the employee specifically.

R&P mails the new hires survey questionnaire out twice. The first mailing is sent to all employers chosen to be in that quarter’s sample and the second mailing is sent approximately three weeks later to employers who did not respond to the first. Phone calls are then made to employers that did not respond to either mailing. Table 1 shows that although response rates vary by industry and quarter, R&P has attained at least a 70% response rate for nearly every quarter used in this analysis.

Although R&P has used just four quarters of data to produce employment estimates in the past, eight quarters of data (2010Q4-2012Q3) were used for this particular article. This was done because R&P samples a relatively small number of employers each quarter and small samples can distort estimates. Adding together two years of data improves these estimates.

More information about the methodology, including why new hires were chosen to represent jobs in the state and a more detailed explanation of the sampling methodology, as well as the complete results of this survey can be found at http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/newhires.htm. A copy of the questionnaire used for this survey is available in Appendix C of the ARRA Labor Dynamics: An Overview of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 as it Pertains to the Wyoming Department of Employment's Research & Planning Section and the Rocky Mountain and Northern Plains Consortium (Manning, Jones, Knapp, Leonard, & Saulcy, 2011), which is available at http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/occasional/occ5.pdf.

Results

One purpose of this article is to explore how new hires jobs in the education industry compare to those in the health care industry, and how jobs in both industries compare to those in all industries combined. The educational services industry (NAICS 61; referred to in this article as the education industry or just education) includes public and private primary and secondary schools, colleges and trade schools, tutoring services, educational support services, and survival training programs. The health care and social assistance industry (NAICS 62; referred to in this article as the health care industry or just health care) includes offices of physicians, dentists and chiropractors, home health care, hospitals, nursing care facilities, services for people with disabilities, child services including Head Start Programs and daycare, and vocational rehabilitation services.

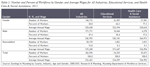

As noted in the introduction to this article, these two industries were chosen partly because R&P has done research on them in the past, but also because there are many similarities between them. Both industries deal with a large client base on a daily basis — workers in the education industry work with students while those in the health care industry work with patients. In general, wages tend to be higher in both the health care and education industries than across all industries combined (see Table 2) and employees in both tend to have better access to workplace benefits (Manning & Saulcy, 2013). Finally, both industries employ larger proportions of female workers compared to the totals for all industries combined (see Table 2). For more information about earnings by industry, age, and gender in Wyoming, please see http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/earnings_tables/2013/index.html.

Occupations, Gender, and Turnover

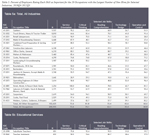

There were 7,323 new hires in education and 15,063 new hires in health care from 2010Q4 to 2012Q3. More than three-fourths of the new hires in each of those industries were in the 20 occupations with the largest numbers of new hires. By comparison, the 20 largest occupations in all industries accounted for just over half (51.2%) of all new hires (see Table 3).

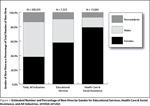

Females accounted for more than half of all new hires in both the education and the health care industries (see Figure 1). As Table 3b shows, females accounted for 57.7% of all new hires in education and made up at least half of all new hires in 15 of the 20 top occupations, including elementary school teachers, except special education (71.4%) and adult literacy, remedial education and GED teachers (83.3%). Females accounted for 78.9% of all new hires in health care (see Table 3c) and made up at least half of all new hires in every one of the top 20 occupations. In contrast, females comprised only 37.9% of all new hires across all industries, although more than half of new hires in seven of the 20 largest occupations were females (see Table 3a).

As mentioned previously, nonresidents are those individuals who do not possess a Wyoming driver’s license. Demographic data such as age and gender are not available for these individuals. Overall, the proportion of nonresident new hires across all industries was 13.4% and at least one in five new hires in six of the top 20 occupations was a nonresident (see Table 3a).

By comparison, only 9.3% of new hires in education were nonresidents and there were only two occupations in which nonresidents accounted for at least 20% of the total: educational, vocational, and school counselors (33.3%) and coaches and scouts (21.1%). Likewise, only 7.0% of new hires in health care were considered nonresidents. Nonresidents accounted for at least 20% of all new hires in only two of the top 20 occupations: maids and housekeeping cleaners (28.6%) and preschool teachers, except special education (20.0%).

Turnover rates are defined in this article as the percentages of new hires who left their employer by one quarter after they were hired. Turnover rates were lower for new hires in the health care industry (15.3%; see Table 3c) than in the education industry (23.8%; see Table 3b), or across all industries (23.6%; see Table 3a). Turnover in education may be higher because of the seasonal nature of many of the occupations in that industry, such as substitute teachers; coaches and scouts; and lifeguards, ski patrol, and other recreational professionals. Turnover rates for new hires in education were highest among substitute teachers (42.4%), self-enrichment education teachers (40.0%), and coaches and scouts (52.6%). In comparison, turnover rates for new hires working in health care were highest for home health aides (61.5%), receptionists and information clerks (37.5%), and child care workers (36.0%).

Wages and Benefits

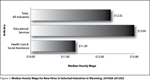

The average hourly wage for new hires across all industries and in educational services and health care & social assistance is shown in Figure 2. Across all industries, the median hourly wage for new hires was $12.32 (see Table 4a. However, the average hourly wage was lower for 14 of the top 20 occupations across all industries.

For new hires in education (see Table 4b), the median wage for all workers was slightly higher at $13.00 per hour. The median hourly wage was higher in eight of the top 20 occupations. For example, the median wage for educational, vocational, and school counselors was $24.42 per hour and the median wage for vocational education teachers, post-secondary was $26.66 per hour.

The median wage for all new hires working in health care was $11.29 per hour, and the median wage was higher in nine of the top 20 occupations (see Table 4c). For example, the median hourly wage was $23.00 for registered nurses and $27.75 for dental hygienists.

New hires in education and health care were offered access to most benefits at a greater rate than new hires across all industries. As shown in Table 4a, 31.8% of new hires across all industries were offered health insurance, while 22.1% were offered retirement benefits and 26.8% were offered paid time off. In comparison, 32.6% of new hires in education (see Table 4b) were offered health insurance, 34.5% were offered retirement benefits, and 25.5% were offered paid time off. Among new hires in health care (see Table 4c), 35.8% were offered health insurance, 32.7% were offered retirement benefits, and 45.9% were offered paid time off.

There are some notable examples of occupations that were offered benefits at a much higher rate than the average. For example, of the estimated 103 child care workers in education, 100.0% were offered health insurance, retirement benefits, and paid time off. Of the 103 middle school teachers, except special education, 100.0% were offered health insurance and retirement benefits and 62.5% were offered paid time off. Similarly, 85.7% of protective service workers, all other, working in health care were offered health insurance, retirement, and paid time off, and 71.4% of maids and housekeeping cleaners working in health care were offered health insurance while 78.6% were offered paid time off.

Job Skills

Employers were asked to rate the importance of five skills for fulfilling the duties of the new hire’s job: service orientation, critical thinking, reading comprehension, technology design, and operation and control. Service orientation was considered important by a larger proportion of employers for jobs in education (80.6%; see Table 5b) and health care (88.9%; see Table 5c, page 13) than for jobs across all industries (73.6%; see Table 5a). Critical thinking was rated important for a larger proportion of jobs in health care (87.2%) than in education (78.5%) or across all industries (74.1%). Similarly, reading comprehension was rated important for a larger proportion of employers in health care (80.6%) than in education (74.3%) or all industries (63.1%). However, operation and control was rated important for a smaller proportion of jobs in education (46.0%) and health care (50.2%) than across all industries (60.8%). There was very little difference in the proportion of jobs for which technology design was rated important in education (35.6%), health care (39.2%), or all industries (35.4%).

In the education industry (see Table 5b), service orientation was rated important for 100.0% of jobs in six of the top 20 occupations, including elementary school teachers, except special education; office clerks, general; and educational, vocational, and school counselors. This skill was also rated important for a large proportion of jobs in occupations such as teacher assistants (90.5%), middle school teachers, except special education (87.5%), and coaches and scouts (89.5%). Critical thinking was rated important for 100.0% of jobs in six occupations of the top 20, including elementary school teachers, except special education, and adult literacy, remedial, and GED teachers. Other occupations for which this skill was rated important included substitute teachers (92.4%) and middle school teachers, except special education (87.5%). Reading comprehension was rated important for many occupations such as elementary school teachers, except special education (100.0%) and vocational education teachers, post-secondary (93.8%). Although technology design was rated important for only 35.6% of all new hires jobs in education, if was considered important for 100.0% of jobs in educational, vocational, and school counselor occupations and adult literacy, remedial education, and GED teacher occupations. Similarly, although operation and control was rated important for less than half of these jobs (46.0%), it was considered important for 100.0% of landscaping and groundskeeping jobs and 88.0% of school bus drivers jobs.

In the health care industry (see Table 5c), service orientation was rated important for six of the top 20 occupations, such as nursing assistants, dental hygienists, and physical therapist assistants. This skill was also rated important for a large proportion of jobs in several other occupations, including personal and home care aides (95.7%) and registered nurses (95.3%). Critical thinking was rated important for all jobs in five of the top 20 occupations, including registered nurses, recreation workers, and protective service workers, all other. Other occupations with a large proportion of jobs for which this skill was considered important included nursing assistants (96.2%) and social and human service assistants (94.4%). Reading comprehension was also considered important for 100.0% of jobs in five of the top 20 occupations, including registered nurses; cooks, institution and cafeteria; and physical therapist assistants. Technology design was rated important for just 39.2% of all new hires jobs in health care, but it was important for 83.3% of secretaries, except legal, medical, and executive and 79.1% of registered nurses. Although operation and control was only rated important for half of all jobs in this industry (50.2%), it was rated important for 100.0% of cooks, institution and cafeteria, and 90.0% of dental hygienists.

Conclusions

As indicated in the introduction, there were two purposes to this article. The first was to compare characteristics for jobs filled in the health care industry, the education industry, and all industries combined. This comparison has shown that the median wage for all new hires ($12.32) wasn’t much different from that of new hires in the education ($13.00) or health care ($11.29) industries, but new hires in education and health care tended to fill jobs that typically required a higher level of education. New hires in health care and education were more often female than male. There wasn’t a large difference in the proportion of all new hires that received health insurance or paid time off benefits compared to new hires in education or health care, although a greater proportion of those in education and health care were offered retirement benefits. All of the skills employers were asked to rate were rated as important for a larger proportion of jobs in education and health care. This was especially true for jobs in health care.

Another purpose of this article has been to provide an introduction to the data elements collected by this survey and show how they can be combined to help inform the curriculum decisions of educators and training providers as well as the career choices of students and job seekers. For example, both educators in nursing programs and students interested in pursuing a career in nursing can see that registered nurses accounted for 6.7% of all new hires in health care. They would see that a job as a registered nurse typically requires an associate’s degree and that skills such as service orientation, critical thinking, and reading comprehension were considered important for most jobs in that occupation by employers. They would find that, in Wyoming, newly hired registered nurses working in the health care industry earned a median wage of $23.00 per hour and half of the jobs in that field were offered paid time off, while slightly less than half were offered health insurance or benefits. They could also compare registered nurses working in the health care industry to registered nurses working in other industries, such as education or public administration (government) to see how these characteristics differ depending on the kind of environment they work in. These details can be used by educators to create curriculums that emphasize building critical thinking and reading comprehension skills as well as help students and potential students understand the economic aspects of the jobs they will be filling. Students and potential students can use these data to evaluate the job against their own skill sets and what they want in a job and use that evaluation to decide if a career in nursing is the right choice for them.

Another example of how these data can be used involves comparing data for one occupation across several industries to determine differences in work environments. If, for instance, a job seeker was interested in a job as a janitor but did not know if he wanted to work at a hospital or a school, he could compare characteristics for janitors and cleaners, except maids and housekeeping cleaners in the health care and education industries, as well as in all industries combined. This occupation was among the top 20 largest occupations in education and all industries, but was the 43rd largest occupation in the health care industries; information for janitors in health care is not included in the tables used for this article but can be found on R&P’s website (http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/newhires.htm).

By comparing wages across industries, the job seeker would see that janitors in all industries earned a median wage of $11.00 per hour, compared to $12.32 per hour in education and $14.00 per hour in health care. This comparison would also show that nearly one-third (30.8%) of janitors in education were offered health insurance, compared to only 8.6% of those working in all industries and none of those working in health care. Similarly, although no janitors in health care were offered retirement benefits, 8.9% of those in all industries and 35.9% of those in education were offered the benefit. However, one-third (33.3%) of janitors in health care were offered paid time off compared to a quarter of those working in education (25.6%) and 14.4% of those working in all industries. A comparison of the skills needed for this occupation would show that service orientation is considered important by a larger proportion of employers in education (64.1% compared to 55.9% in all industries and 33.3% of those in health care) and reading comprehension is considered important by more employers in health care (66.7% compared to 47.1% of those in all industries and 43.6% of those in education).

References

Cowan, C., Jones, S.D., Knapp, L., Leonard, D.W., & Saulcy, S. (2008, March). Nurses in demand: A statement of the problem. Casper: Wyoming Department of Employment, Research & Planning. Accessed November 27, 2013, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/nursing_demand_08.pdf.

Gallagher, T., Glover, T., Harris, P., Knapp, L., Manning, P., & Moore, M. (2012, Fall). Monitoring school district human resource cost pressures: A report to the Wyoming Joint Education Committee. Casper: Wyoming Department of Workforce Services, Research & Planning. Accessed November 27, 2013, from http://doe.state.wy.us/lmi/education_costs/education_costs.pdf.

Gallagher, T., Glover, T., Bullard, D., Harris, P., Holmes, M., Knapp, L., Manning, P., & Moore, M. (2013, Fall). Monitoring school district human resource cost pressures: A report to the Wyoming Joint Appropriations Interim Committee and the Joint Education Interim Committee. Casper: Wyoming Department of Workforce Services, Research & Planning. Accessed November 27, 2013, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/education_costs/2013/monitoring_2013.pdf.

Harris, M.A., Jones, S.D., Knapp, L., & Leonard, D.W. (2008, August). Retention of nurses in Wyoming. Casper: Wyoming Department of Employment, Research & Planning. Retrieved November 27, 2013, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/nursing_retention_08.pdf.

Jones, S.D. (2009). Succession planning and satisfaction measures in public health. Casper: Wyoming Department of Employment, Research & Planning. Accessed November 27, 2013, from http://doe.state.wy.us/lmi/phn_09/title.htm.

Knapp, L. (2013). What do Wyoming employers want? Evidence from the new hires survey. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 50(11). Retrieved January 29, 2014, from http://doe.state.wy.us/lmi/trends/1113/a1.htm.

Knapp, L. (2011). New hires in Wyoming: An in-depth analysis. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 48(2). Retrieved December 5, 2013, from http://doe.state.wy.us/lmi/0211/a2.htm.

Manning, P., & Saulcy, S. (2013). Wyoming benefits survey 2012. Casper: Wyoming Department of Workforce Services, Research & Planning. Accessed November 27, 2013, from http://doe.state.wy.us/lmi/benefits2012/index.htm.

Manning, P., Jones, S.D., Knapp, L., Leonard, D.W., & Saulcy, S. (2011, May). ARRA Labor Dynamics: An overview of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act as it pertains to the Wyoming Department of Employment Research and Planning Section and the Rocky Mountain and Northern Plains Consortium. Casper: Wyoming Department of Workforce Services, Research & Planning. Accessed January 29, 2014 from http://doe.state.wy.us/lmi/occasional/occ5.pdf.