Chapter 4: Postsecondary Education and Labor Market Behavior

Research & Planning (R&P) uses longitudinal analysis to study the behavior of people of different ages, gender, and educational attainment in the labor market. In Youth Transitions: Life Events and Labor Market Behavior, Harris (2015) found that major life events, such as marriage and the birth of a first child, occur for young adults in their early twenties. Harris also found that age, not gender, is a factor in the continuity of employment. As individuals in selected cohorts aged, stable work opportunities improved at similar rates for males and females. In the forthcoming paper titled, Workforce Turnover & Continuous Employment: The Importance of the Distribution of Age & Gender, Halama (in press) also found the turnover rate continued to decrease with age. In first quarter 2015 (2015Q1), individuals ages 23-24 experienced lower turnover (39.8%) than individuals ages 20-22 (47.8%). Mean quarterly wages also increased with age. In 2015Q1, individuals ages 23-24 earned an average quarterly wage that was $1,690 higher than the average quarterly wage for those ages 20-22. This chapter uses longitudinal analysis to examine the approximate age at which Wyoming high school students make major life decisions, such as enrolling in and completing postsecondary education or migrating to another state, and how those decisions affect labor market outcomes.

Upon high school completion, students may go directly into the workforce or into postsecondary education. For some, leaving high school may mean more extensive employment in the market, since many students work at some point during high school. For the purposes of this research, R&P defines students who do not enroll in postsecondary education and do not earn wages in Wyoming or one of the states with which R&P has a data sharing agreement as not found.

|

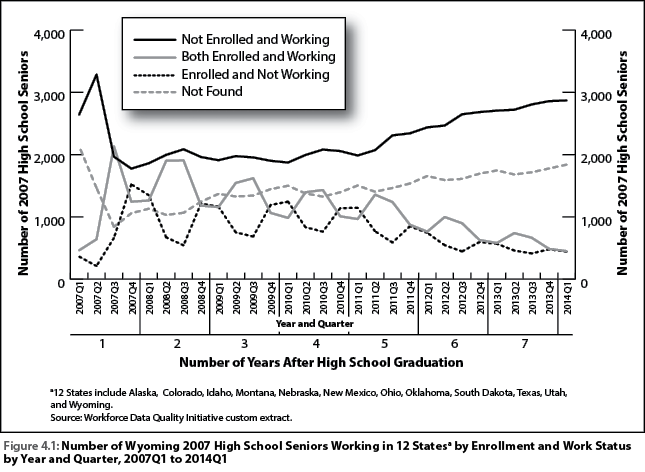

According to WDQI Report No. 1 (Gallagher, T., Glover, T., Hammer, L., Holmes, M., & Moore, M., 2014), 5,598 students made up the 2007 senior cohort – students who were scheduled to graduate at the completion of the 2006/07 school year. Figure 4.1 shows the 2007 cohort by enrollment and work status over a seven-year period. A student’s status may change for several reasons, such as enrolling in and withdrawing from postsecondary education, or leaving a job in Wyoming or a partner state to enroll in postsecondary education or for a job in a state with which R&P does not have a data sharing agreement. Each of the 5,598 students from the 2007 senior cohort is accounted for in Figure 4.1 for each quarter based on their enrollment and work status.

Students who enrolled in postsecondary education experienced more seasonality in employment than students who did not enroll in postsecondary education. Figure 4.1 shows that the number of students enrolled and working at the same time peaked in quarters two and three each year and dropped in quarters one and four. The amplitude of this seasonal pattern diminishes over time. On the other hand, the number of students enrolled and not working decreased in the second and third quarters and increased during the school year, or in quarters one and four. Over time the number of students enrolled in postsecondary education decreased, and at the same time the number of students that fluctuated in the seasons between enrolled and working and enrolled and not working also decreased. The most substantial change in the seasonal pattern of students enrolled in postsecondary education occurred in 2011Q3, when the number of students enrolled began a downward trend as students graduated or withdrew from their postsecondary institutions. During the same period, the number of Wyoming high school students not enrolled and working or not found in R&P’s database increased. The shift from postsecondary education to the workforce without postsecondary education occurs gradually for this cohort, and then the number of students enrolled and the number of students not enrolled begins to diverge about four years after 12th grade.

|

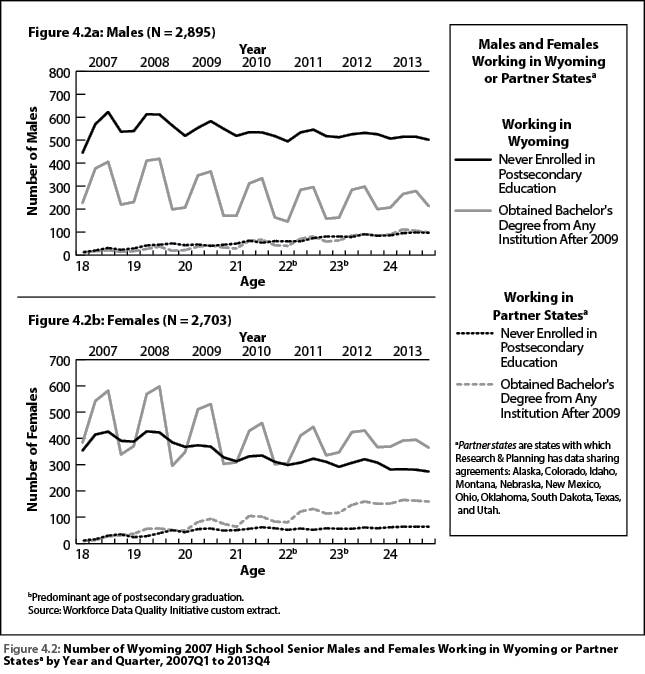

The number of students who never enrolled in postsecondary education (students with no records in the National Student Clearinghouse database through 2014) and the number of students who went on to obtain a bachelor’s degree varied between males and females. Figure 4.2 shows the number of Wyoming high school males and females who either earned a bachelor’s degree or never enrolled in postsecondary education and worked in Wyoming or a state with which R&P has a data sharing agreement. The status of these individuals may fluctuate between working in Wyoming and working in partner states as individuals migrate in and out of Wyoming and partner states for employment. As shown in Figure 4.2a, the number of males who went on to obtain a bachelor’s degree and worked either in Wyoming or a partner state followed a seasonal pattern, indicating some instability as individuals accept and leave jobs. Around age 23, the magnitude of the seasonal fluctuations of employment of males with a bachelor’s degree begins to decrease. The average number of males who obtained a bachelor’s degree and worked in Wyoming remained steady and at the same time, the average number of males who had a bachelor’s degree and worked in a partner state began to increase, indicating that after obtaining their bachelor’s degree, males found jobs in partner states.

The seasonal pattern in the number of males who never enrolled and worked in Wyoming decreased at an earlier age than for males who obtained a bachelor’s degree. Around age 21, this seasonal pattern began to diminish, and by age 24 only about 500 out of 1000 males who never enrolled in postsecondary education from the 2007 senior cohort worked in Wyoming. The decrease in the seasonal pattern for males who never enrolled and males who obtained a bachelor’s degree, and the increase of males working in a partner state, suggest that once males reach their early twenties, regardless of educational attainment, they find more continuous employment, often outside of Wyoming.

Of the 2,703 females in the 2007 Wyoming high school senior cohort, 696 never enrolled in postsecondary education. As shown in Figure 4.2b, more females with a bachelor’s degree worked in Wyoming than females who never enrolled in postsecondary education. The number of females who obtained a bachelor’s degree and worked followed a seasonal pattern that diminished around age 23. A seasonal pattern also existed for the number of females with a bachelor’s degree who worked in a partner state and continued an upward trend through age 24. The number of females who never enrolled in postsecondary education and worked in a partner state remained consistent through age 24, while the number of females who never enrolled and worked in Wyoming steadily declined from age 18. These data suggest that females may be more motivated to leave the state for a better job opportunity or a job requiring their degree.

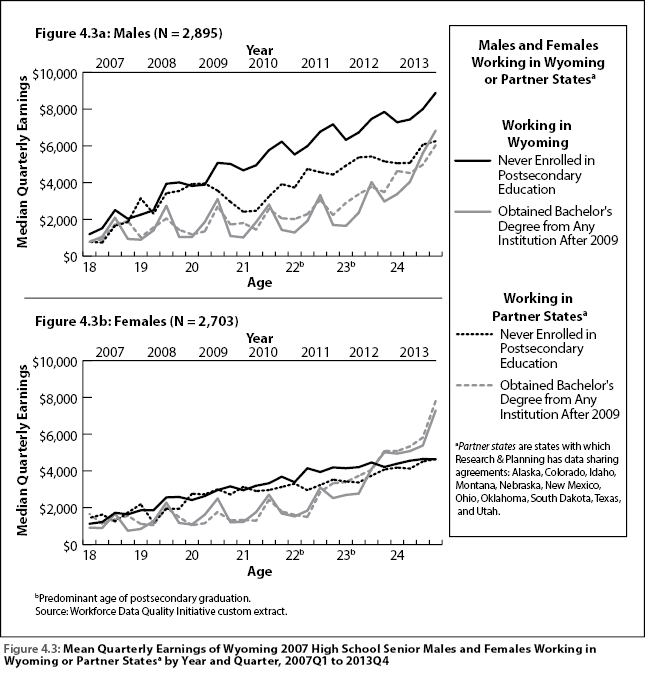

High school students in the 2006/2007 senior cohort who went directly into the workforce earned higher wages than students who enrolled in postsecondary education. According to “The Education and Work Experience of Youth in Wyoming’s Counties” (Mohondro, 2016), in 2010, students from the 2007 senior class who did not enroll in postsecondary education earned an annual median wage more than double that of students who did enroll in postsecondary education. This finding corresponds with Figure 4.3a, which shows that males who never enrolled in postsecondary education and worked in Wyoming earned higher wages than males with a bachelor’s degree until about age 24.

Median quarterly wages remained low and seasonal for males who earned a bachelor’s degree and worked either in Wyoming or a partner state until about age 22, when the slope of the earnings gain became more positive (see Figure 4.3a). The median quarterly earnings of males who never enrolled in postsecondary education and worked in Wyoming increased steadily with much less fluctuation between seasons than the quarterly wages of males with a bachelor’s degree, indicating more continuous employment.

|

As shown in Figure 4.3a, males who never enrolled in postsecondary education and worked in a partner state earned wages similar to males who never enrolled and worked in Wyoming until age 20. After age 20, males who never enrolled and worked in a partner state earned between $1,000 and $2,000 less in a quarter than males who never enrolled in postsecondary education and worked in Wyoming. Males with a bachelor’s degree working in Wyoming earned wages similar to that of males with a bachelor’s degree working in a partner state until age 24, but earned less than males who did not enroll in postsecondary education. By age 24, males who worked in Wyoming, whether they had a bachelor’s degree or never enrolled in postsecondary education, earned more money than males working in a partner state. This suggests that something other than high wages motivates males to find employment in other states.

Similar to males, females who do not enroll in postsecondary education earn higher wages initially than females who eventually obtain a bachelor’s degree (see Figure 4.3b). Females with a bachelor’s degree who worked in Wyoming or a partner state experienced an increase of wages at age 22 and earned higher quarterly wages than females who, by age 23, never enrolled in postsecondary education. By age 24, females with a bachelor’s degree who worked in a partner state earned about $500 more per quarter than females with a bachelor’s degree who worked in Wyoming and over $2,000 more per quarter than females who never enrolled in postsecondary education (see Figure 4.3b). These data suggest that postsecondary education is more important for females to earn higher wages, and that while they may need to leave Wyoming to find jobs, they may not earn higher wages in another state.

As noted earlier, major life events occur during a young adult’s early twenties and affect their labor market outcomes. Young males and females may make decisions about education that result in different outcomes; for example, obtaining a bachelor’s degree may not affect earnings for males in the same way it affects females, and finding employment in their chosen field may encourage females to leave Wyoming, even if they earn less in a partner state.

Upon leaving high school, students face decisions that could influence their labor market behavior in the near future. Longitudinal analysis and administrative databases available only to R&P allow for the unprecedented study of the different labor market behaviors and outcomes of Wyoming high school students. The different directions taken by the 2007 Wyoming high school senior class provide insight into how decisions made about postsecondary education affect earnings and migration years later. As former Wyoming high school students continue to age, R&P will continue to use longitudinal analysis to research the directions in which these students travel.

References

Gallagher, T., Glover, T., Hammer, L., Holmes, M., & Moore, M. (2015, April). Workforce Data Quality Initiative Report No. 1 for Wyoming: School Attendance and Employment, 2006 to 2013. Retrieved April 29, 2016 from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/education_we_connect/WDQI_Pub1.pdf

Halama, M. (in press). Workforce Turnover & Continuous Employment: The Importance of the Distribution of Age & Gender.

Harris, P. (2015, May). Youth transitions: Life events and labor market behavior. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 52(5). Retrieved April 29, 2016, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/trends/0515/a1.htm

Mohondro, L. (2016, February). Occasional Paper No. 8: The Education and Work Experience of Youth in Wyoming’s Counties. Retrieved April 29, 2016, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/occasional/occ8.pdf