Excerpt from 2008 Wyoming Job Vacancy Survey

This article examines selected results of a job vacancy study of Wyoming health care firms conducted by Research & Planning (R&P) in 2007 and 2008. The results showed 230 openings in ambulatory health care services, 423 in hospitals, and 107 in nursing & residential care facilities. The highest vacancy rate for registered nurses was in hospitals. Nursing & residential care vacancies were unfilled the longest of any health care subsector. By quantifying the characteristics of demand for labor, stakeholders could improve their recruitment and retention efforts.

The demand for nurses in Wyoming is expected to increase as more nurses reach traditional retirement age (Saulcy, 2008). To evaluate the nursing situation in the state, the Wyoming Healthcare Commission contracted with R&P during 2007 to provide a study of vacancies, recruitment, and retention among health care firms (see all reports online, including the one from which this article was excerpted, at http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/nursing.htm). This article focuses on job vacancies in health care, with special attention paid to openings for nurses. The data represent initial job openings rather than final hiring terms.

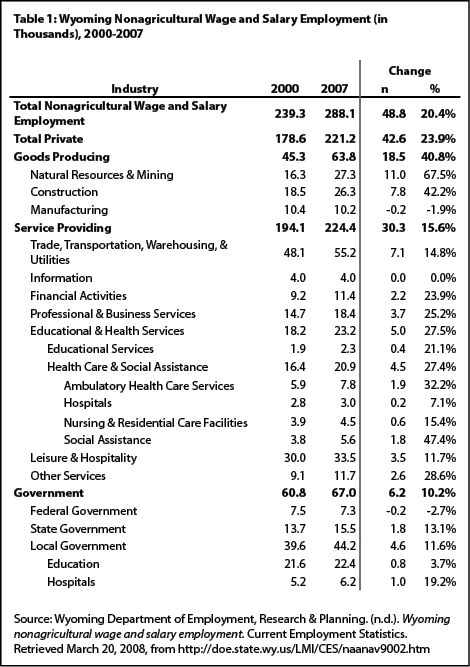

At the time the study was conducted, Wyoming was in a period of substantial employment growth driven by energy expansion. In 2000, total employment in the state was 239,300 (see Table 1). By 2007, employment had risen to 288,100, an increase of 20.4%. Of the 48,800 jobs added in Wyoming, 11,000 were in natural resources & mining. Employment in health care & social assistance rose from 16,400 in 2000 to 20,900, a net gain of 4,500 jobs (27.4%). Within the industry, ambulatory health care services increased the most, from 5,900 to 7,800 (32.2%). Nursing & residential care facilities added 600 jobs (15.4%), while employment in hospitals increased by 200 (7.1%). Much of the growth occurred in firms that serve older populations (Cowan, 2008).

Collecting Data from Different SourcesR&P collected data between January 2007 and early 2008. Data were acquired through two sources: questionnaires and administrative data publicly available on the Internet. The questionnaires were designed to obtain information not available through other statistical or administrative sources. The Internet was used to collect vacancies in hospitals because human resources offices advertise most, if not all, hospital vacancies on their websites. This approach removed the burden of questionnaire response from employers while collecting detailed vacancy information. Using questionnaires is a statistical approach to acquiring information. As such, the responses to various questions tend to be more uniform. For example, the questionnaire largely standardized the method by which occupation titles for vacancies were reported. In addition, data collected from primary sources like questionnaires often can be clarified by following up with respondents. Conversely, data collected from administrative sources, such as vacancies posted on the Internet, are less uniform in content, particularly when the information is collected from several entities (in this case, hospitals). Also, because administrative data serve nonstatistical purposes, researchers must accept the information as is.

Data from two different sources used for different purposes cannot automatically be analyzed together. This study first required standardizing the reported vacant occupations by assigning a Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) code to each occupation, whether the information was collected from a questionnaire or from the Internet. SOC classifies occupations according to broad sets of knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs). This approach simplifies both data collection and analysis by reducing occupations to common sets of KSAs. It also makes data easier to understand by collapsing large numbers of otherwise distinct occupations into general groups. For this study, standardization was especially important for vacancy information obtained from the Internet. Vacancies reported on the Internet tend to include both common KSAs and KSAs unique to particular positions. With the shared occupational characteristics as the focus, SOC codes were used to evaluate the need for various sets of KSAs. For example, a hospital may publicize a variety of titles for vacant registered nurse (RN) positions such as telemetry nurse, labor and delivery nurse, and operating room nurse. Alternatively, an ambulatory health care firm may report titles such as family nurse practitioner and certified nurse anesthetist. However, when occupations are classified by SOC, all these are considered RNs. The assignment of SOC code based on common KSAs allows evaluation of data that initially seem dissimilar. For more detail about the methodology, see the full report at http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/nurse_vacancies_retention.pdf.

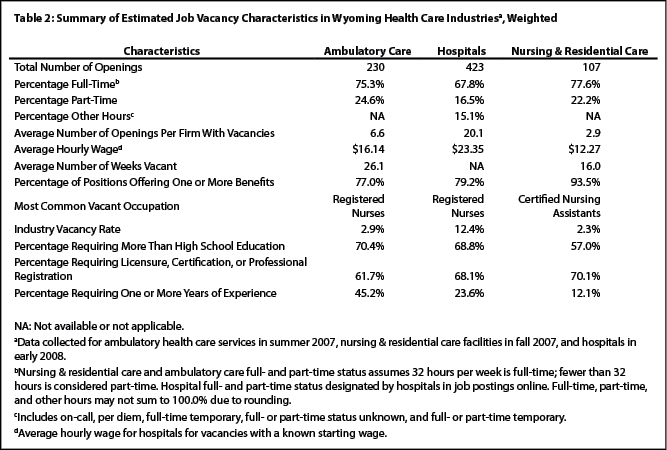

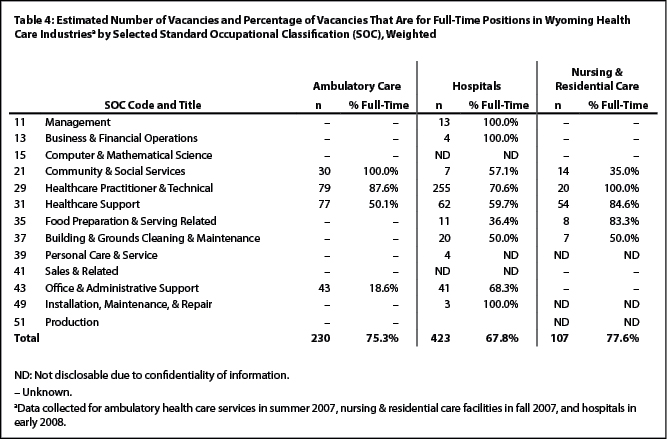

Job Vacancies by Industry SubsectorSurvey results showed 230 openings in ambulatory health care services, 423 in hospitals, and 107 in nursing & residential care facilities (see Table 2). The average number of openings per firm was 6.6 in ambulatory care, 20.1 in hospitals, and 2.9 in nursing & residential care. The most common ambulatory care and hospital vacancy was for RNs. For nursing & residential care, the most common vacancy was for certified nursing assistants (CNAs).

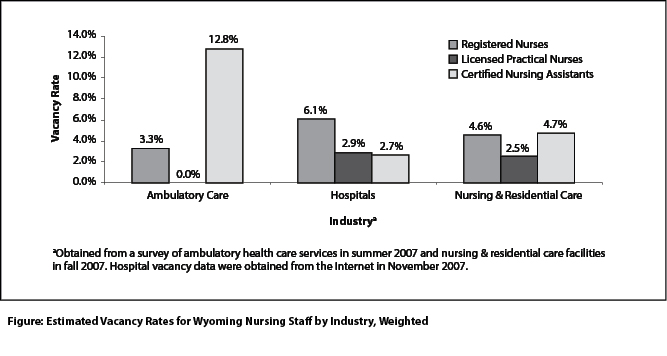

In addition to estimating the average number of openings, vacancy rates were also calculated. Rates by occupation and industry were calculated as a percentage for nursing occupations. The calculation was total estimated vacancies by occupation or industry divided by the sum of estimated vacancies and estimated occupational employment by industry from the Occupational Employment Statistics (OES) survey (see http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/oes.htm for more information about OES). The highest vacancy rate was for hospitals (12.4%), followed by ambulatory care (2.9%) and nursing & residential care (2.3%). It is possible that the lower vacancy rate in nursing & residential care was at least partly a result of administrative regulations requiring a minimum staff-to-patient ratio (Leonard, 2008a).

Across the three health care industries, the highest advertised average hourly wage for open positions was in hospitals ($23.35), while the lowest was in nursing & residential care ($12.27). By comparison, the OES (2008) program estimated as of March 2008 that the Wyoming average hourly wage was $19.97 in hospitals and $14.01 in nursing & residential care. According to OES data (2008), Wyoming’s mean hourly wage was $26.03 per hour for RNs and $17.90 per hour for licensed practical nurses (LPNs). For CNAs, the mean hourly wage was $11.66, $14.37 per hour less than for RNs and $6.24 per hour less than for LPNs. A report by Leonard and Szuch (2008) showed that in fourth quarter 2007, CNAs earned lower wages than RNs and LPNs in all three health care subsectors. The report also showed that the highest concentration of CNAs was in nursing & residential care facilities. The combination of a higher number of CNA openings and lower wages most likely yielded the lower average wage in nursing & residential care.

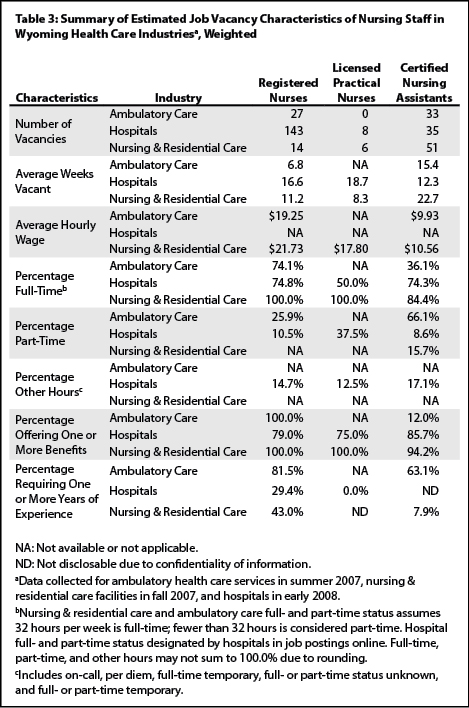

Nurse Vacancy CharacteristicsTable 3 shows the vacancy characteristics of nursing occupations. Most RN vacancies (143) were in hospitals, followed by ambulatory health care services (27) and nursing & residential care facilities (14). Research by Leonard (2008b) found that 118 to 169 nurses became registered in Wyoming between 2001 and 2003. Provided that this trend held through 2007, even if the maximum of 169 individuals gained employment in the state for the estimated vacancies in this study, the number of graduates would be insufficient to cover the 184 total RN vacancies in health care.

CNA vacancies in nursing & residential care were open for the greatest length of time (22.7 weeks on average), followed by CNAs in ambulatory care (15.4). Factors that Fitzpatrick (2002) suggested may contribute to the problem were working conditions and comparatively low wages. Studies by Ong, Rickles, Matthias, and Benjamin and by Riemer (as cited in Bullock & Waugh, 2004) indicated that CNAs “whose highest degree is a high school diploma are among the ranks of the working poor, often drawing on public assistance intermittently” (p. 769).

In Wyoming, recruiting sufficient CNAs may be further complicated by escalating wages in other industries as a result of Wyoming’s economic expansion. Research by Leonard (2007) found that from third quarter 2005 to third quarter 2006, the average quarterly wage for CNAs employed in health care or government rose by $505. In contrast, CNAs working in industries other than health care experienced average quarterly wage growth of $616. Wage growth for CNAs employed in natural resources more than quadrupled wage gains for other non-health care industries. In third quarter 2005, the 17 CNAs employed in natural resources & mining earned an average quarterly wage of $6,296. By third quarter 2006 there were 35 CNAs employed in natural resources & mining earning an average quarterly wage of $9,189, an increase of $2,893.

By occupation, vacancy rates were highest for CNAs in ambulatory health care services, while the lowest rate was for LPNs in nursing & residential care facilities (see Figure). The low rate for LPNs may have been at least partly due to the fact that LPNs were employed in lower numbers than either RNs or CNAs. The highest vacancy rate for RNs was in hospitals (6.1%), which may have been the result of hospitals having to attract employees from a larger labor market (Harris, 2007, 2008).

Vacancy Characteristics of Major Occupational GroupsThe majority of open positions were concentrated in two major occupational groups: healthcare practitioner & technical and healthcare support (see Table 4). These two groups include RNs, LPNs, and CNAs. Healthcare practitioner & technical occupations typically require higher levels of education or experience to be considered qualified for the position than do healthcare support occupations. By far the largest number of openings by SOC and industry were in healthcare practitioner & technical occupations for hospitals (255 vacancies). A significant number of office & administrative support occupations were also open in ambulatory care and hospitals (43 and 41, respectively).

SummaryThe ability of Wyoming’s health care delivery system to meet the needs of the state’s aging population depends on substantial numbers of staff and professionals. Nurses are an especially important component of the health care delivery system. As the population ages, more health care services will likely be required. At the same time, nurses will be retiring or leaving the profession for other reasons. If nurses cannot be retained or new labor made available, the ratio of nurses to patients may decline, potentially affecting patient outcomes (Saulcy, 2008). Hospitals especially are having difficulty finding enough RNs, as demonstrated by the large number of vacant positions. Hospitals’ ability to attract and retain RNs is challenged by the fact that they typically draw from a larger labor market than do nursing & residential care facilities or ambulatory health care services.

The existing education system is unable to fully meet the demand for nurses. Job vacancies are just one component of understanding demand. Use of temporary or contract nurses to meet staffing needs, as well as methods to recruit and retain permanent nursing staff, are discussed in the complete report, Vacancies and Recruitment and Retention Strategies in Health Care, available at http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/nurse_vacancies_retention.pdf.

ReferencesBullock, H.E., & Waugh, I.M. (2004). Caregiving around the clock: How women in nursing manage career and family demands. Journal of Social Issues, 60(4), 767-786. Retrieved September 18, 2008, from http://proxy.lib.wy.us/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/

login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=14989718&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Cowan, C. (2008, March). Chapter 3: A comparison of employment and wages in health care in Wyoming 2000 to 2007. In P. Ellsworth & A. Szuch (Eds.), Nurses in demand: A statement of the problem (pp. 3.1-3.20). Retrieved September 8, 2008, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/nursing_demand_08.pdf

Fitzpatrick, P.G. (2002, Spring). Turnover of certified nursing assistants: A major problem for long-term care facilities. Hospital Topics, 80(2), 21. Retrieved September 9, 2008, from http://proxy.lib.wy.us/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/

login.aspx?direct=true&db=f5h&AN=7217240&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Harris, M.A. (2007, December). Need a nurse? Examining labor sources for health care. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 44(12). Retrieved September 8, 2008, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/1207/a1.htm

Harris, M.A. (2008, August). Using administrative databases to document the source of nurse hires and destination of nurse exits among health care subsectors in Wyoming. In P. Ellsworth & A. Szuch (Eds.), Retention of nurses in Wyoming (pp. 88-94). http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/nursing_retention_08.pdf

Leonard, D.W. (2007, May 7). Secondary data sources and analysis. Presentation to the Wyoming Nurse Advisory Committee, Casper, WY.

Leonard, D.W. (2008a, March). Chapter 2: Projections of registered nurses needed to 2014. In P. Ellsworth & A. Szuch (Eds.), Nurses in demand: A statement of the problem (pp. 2.1-2.13). Retrieved August 7, 2008, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/nursing_demand_08.pdf

Leonard, D.W. (2008b, August). Labor flow components. In P. Ellsworth & A. Szuch (Eds.), Retention of nurses in Wyoming. Retrieved September 9, 2008, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/nursing_retention_08.pdf

Leonard, D.W., & Szuch, A. (2008, August). The NEW report: Nurse employment in Wyoming (NEW), first quarter 2006 through first quarter 2008. Retrieved September 9, 2008, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/NEW_data.pdf

Occupational Employment Statistics Unit (Wyoming). (2008, March). Wyoming occupational employment and wages. Retrieved September 19, 2008, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/EDSPubto20081ECI/TOC001.htm

Saulcy, S. (2008, March). Chapter 1: U.S. and Wyoming demographic profile. In P. Ellsworth & A. Szuch (Eds.), Nurses in demand: A statement of the problem (pp. 1.1-1.12). Retrieved August 7, 2008, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/nursing_demand_08.pdf

Return to text

Return to text

Return to text

Return to text

Return to text

Last modified on

by April Szuch.