Wage Change Analysis Among Exiting Wyoming Executive Branch Employees

The following analysis examines wage changes among persons who left employment (for any reason) from a Wyoming executive branch agency during calendar year 2005. The analysis presented here focuses on state employees, but the method is generic and could be applied to any known subgroup of persons appearing in the administrative databases available to Research & Planning (R&P). A similar study was conducted previously among nurses (Harris, 2008).

Data and Method

Data used for this study included Unemployment Insurance (UI) wage records for Wyoming and partner research states (i.e., Alaska, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, South Dakota, Texas, and Utah), the Wyoming Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW), and the Wyoming Department of Transportation’s driver’s license database. The UI wage records identified a person’s work history and employers, while the QCEW identified the employer’s industry and ownership (e.g., private sector, local government, etc.). Driver’s license records showed a worker’s gender. Calendar year 2005 was the reference period for this study. This period represented the most recent year for which all requisite data were available. The information presented here can be updated on an annual basis as new data become available.

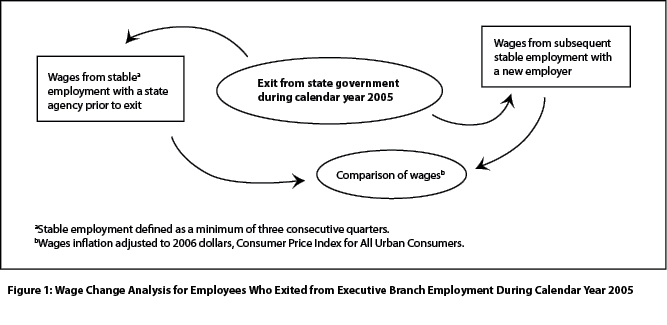

The destination of exit among executive branch employees was determined using methodologies previously developed by Harris (2006). The methodology tracked all exiters regardless of destination (within one year). Previous studies by R&P (Ellsworth, 2006) established that many employees who exited from executive branch employers obtained subsequent employment with another state agency. In relation to wages, this method captured the total quarterly wage data only when a consecutive three-quarter continuous employment relationship with both the prior and subsequent employer existed.1 This procedure eliminated exiters who were temporarily employed in the executive branch prior to leaving or who had not yet obtained stable employment with a new employer. Additionally, both prior and subsequent wages were inflation adjusted to 2006 dollars, using the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers, to make them comparable over time. The average quarterly wage used here did not factor in differences in the number of hours worked and did not distinguish types of pay (e.g., overtime, longevity, etc.). Figure 1 provides a visual description of the basic model.

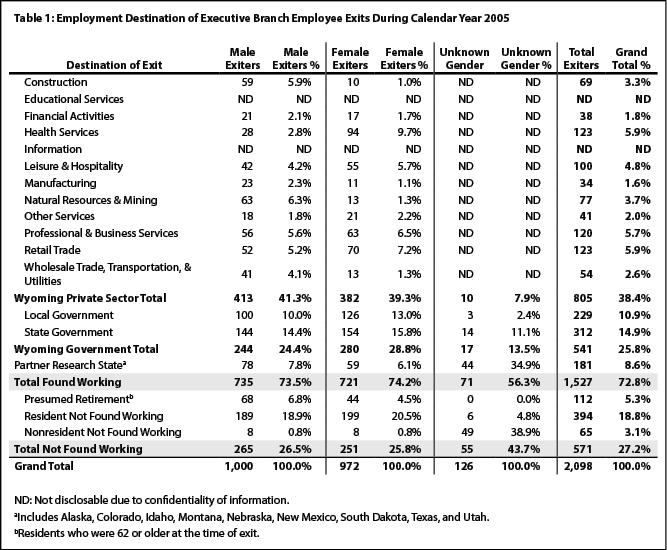

ResultsThere were 2,098 employee exits from Wyoming’s executive branch employers in calendar year 2005 (see Table 1). Some exiters were found working within one year of exit while others were not. The table shows the destination as determined by administrative records, the gender of the exiter when known, and the percentage of the respective column totals. Some data were removed to protect confidentiality. Among 1,527 exiters found working after exiting from an executive branch agency, 805 (38.4% of total exiters) were located in Wyoming’s private sector and 541 (25.8% of total exiters) were working in local or state government, while 181 (8.6% of total exiters) were found working in a partner research state. Additionally, 571 (27.2% of total exiters) could not be located in the administrative records available to R&P.2

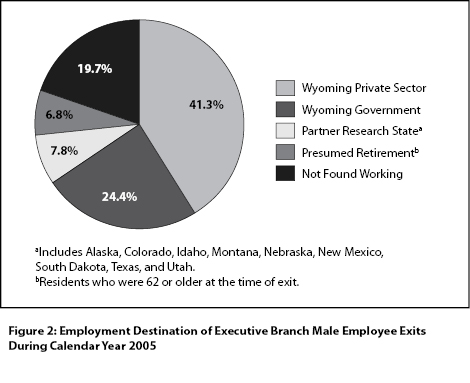

Among a total of 1,000 males, 413 (41.3% of total males) were found working in Wyoming’s private sector after leaving employment in the executive branch (see Figure 2). The top three private sector work destinations were natural resources & mining (63, or 6.3% of total males), construction (59, or 5.9% of total males), and professional & business services (56, or 5.6% of total males). Outside the private sector, 244 male exiters (24.4% of total males) were found working in government, concentrating more heavily in state (144, or 14.4% of total males) than local ownerships (100, or 10.0% of total males). Additionally, 78 (7.8% of total males) were subsequently found working in a partner research state.

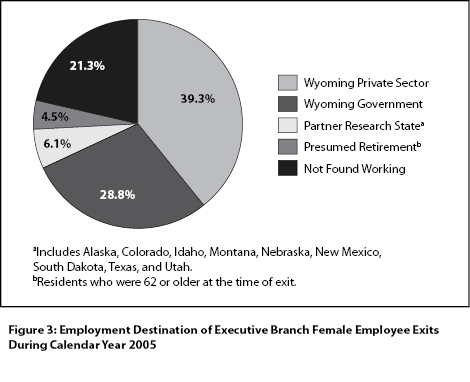

Of 972 total female exiters, approximately an equal percentage of female exiters (39.3%, or 382) were found working in Wyoming’s private sector compared to males (see Figure 3). However, the employment distribution of female exiters among private industry sectors was different than for male exiters. Health services was the top private sector work destination among females (94, or 9.7% of total females). Retail trade was next with 70 female exiters (7.2% of total females) and professional & business services was the third top private sector destination with 63 female exiters (6.5% of total females). As with males, state government had more female exiters than local government (154 versus 126, respectively). Fifty-nine females (6.1% of total females) were found working in a partner research state after exiting from employment in the executive branch.

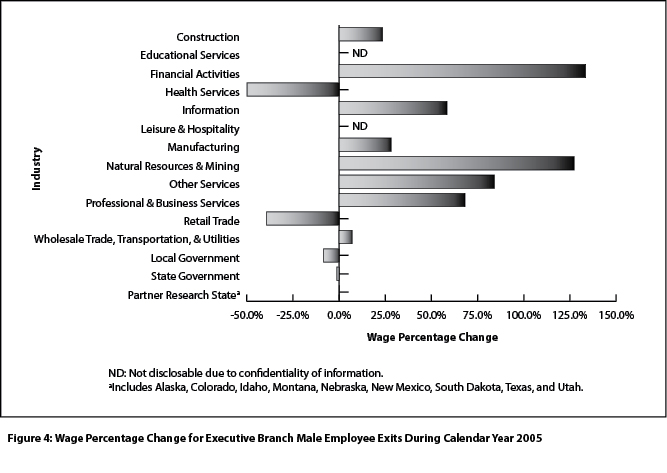

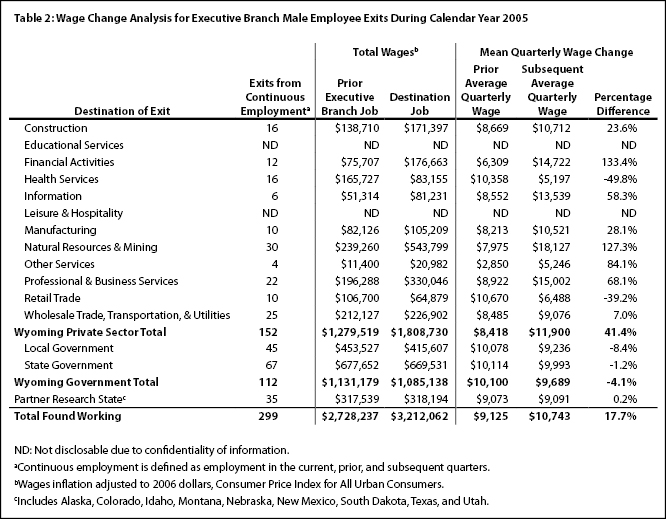

Of the total 735 male exiters subsequently found working, 299 (40.7%) met the continuous employment criteria for inclusion in the wage analysis (see Table 2). Overall, these 299 male exiters had a 17.7% increase in average quarterly wages after exiting from executive branch employment ($9,125 to $10,743). Male exiters who left state government for Wyoming’s private sector had a 41.4% increase in average quarterly wages ($8,418 to $11,900). However, there were substantial differences among industries. Among private sector destinations, educational services and leisure & hospitality had too few cases for display due to confidentiality limitations. In 8 of the remaining 10 private sector destinations, males had an increase in wages; in 5 of those industries, males had a wage increase of more than 50% (see Figure 4). Financial activities and natural resources & mining had the largest increases in average quarterly wages (133.4% and 127.3%, respectively). Other services had the next largest increase (84.1%). Male exiters with subsequent employment in health services and retail trade experienced decreases in average quarterly wages (-49.8% and -39.2%, respectively).

Male exiters subsequently employed in government showed a decrease in quarterly wages for both local and state ownerships (-8.4% and -1.2%, respectively). Average quarterly wages were largely unchanged for male exiters subsequently employed in a partner research state (0.2%).

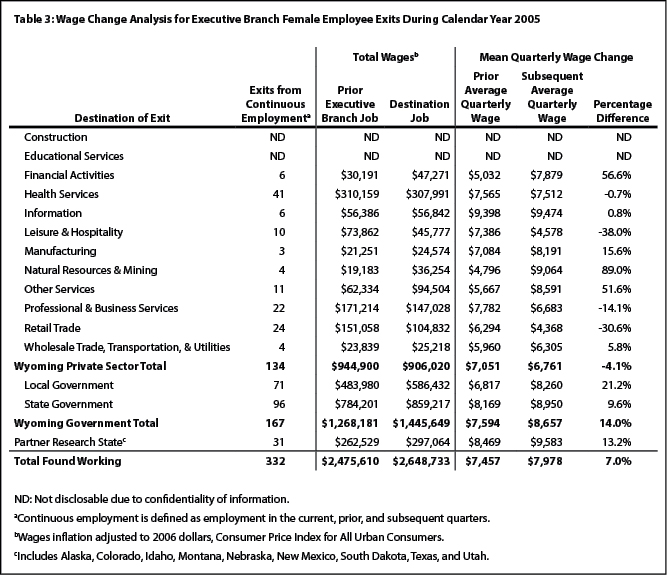

As shown in Table 3, a slightly higher percentage of female exiters met the criteria for inclusion in the wage change analysis (332 of 721, or 46.0%). Overall, these 332 female exiters had a 7.0% increase in average quarterly wages subsequent to exiting from an executive branch agency ($7,457 to $7,978). Female exiters who left state government for Wyoming’s private sector had an overall 4.1% decrease in average quarterly wages ($7,051 to $6,761). Among private sector destinations for female exiters, construction and educational services had too few cases to display due to confidentiality limitations. Females in 4 of the remaining 10 private sector destinations had a decrease in subsequent quarterly wages (i.e., health services, leisure & hospitality, professional & business services, and retail trade). The largest gains in subsequent average quarterly wages for female exiters employed in the private sector were found in natural resources & mining (89.0%), financial activities (56.6%), and other services (51.6%).

Female exiters subsequently employed in government had an increase in quarterly wages for both local and state ownerships (21.2% and 9.6%, respectively). Female exiters subsequently working in a partner research state experienced a 13.2% increase in average quarterly wages.

ObservationsOn the whole, both male and female exiters experienced an average quarterly wage increase after leaving employment with an executive branch agency. The private sector appeared to substantially reward male exiters with increased average quarterly pay while government destinations did not. Partner research states destinations appeared largely neutral in relation to pay for males. Overall, female exiters experienced wage decreases in the private sector but had increases among local and state government destinations and partner research states.

Not all exits from executive branch employment are made with the apparent intent of obtaining higher wages. Relocation to a new area following a spousal employment change may mean difficulty in finding replacement employment at similar or better wages. Additionally, not all job changes resulting in lower wages are necessarily bad (e.g., partial retirement, greater freedom, less stress, new opportunities for growth, etc.). These are issues deserving further research.

ReferencesEllsworth, P. (Ed.). (2006). DOE occupations of concern due to exits and retirement. In Worker retention and factors associated with retirement (pp. 15-21). Retrieved November 19, 2008, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/SP_report.pdf

Glover, W. (2001, December 11). Turnover analysis: Definitions, process, and quantifications. Retrieved October 7, 2008, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/w_r_research/Turnover_Methodology.pdf

Harris, M. A. (2006, December). Where do they come from and where do they go: Wyoming employers compete for older workers. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 43(12), 1-11. Retrieved November 19, 2008, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/1206/a1.htm

Harris, M. A. (2008, August). Using administrative databases to document the source of nurse hires and destination of nurse exits among health care subsectors in Wyoming. In P. Ellsworth & A. Szuch (Eds.), Retention of nurses in Wyoming (pp. 88-94). Retrieved November 19, 2008, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/nursing_retention_08.pdf

1See Glover (2001) for a full description of the continuous employment calculation methodology.

2The not found category included individuals who retired or otherwise withdrew from the labor market, as well as employees not covered by Wyoming Unemployment Insurance. It also included persons who were working but for whom R&P did not have administrative data (e.g., self-employed persons and persons working in states, such as California, where no data sharing agreement exists).

Return to text

Return to text

Return to text

Return to text

Return to text

Return to text

Return to text

Last modified on

by April Szuch.