Comparing Labor Market Outcomes for Nurses, Teachers, State Employees, and a Control Group

To compare jobs requiring advanced training beyond high school that provide opportunities for educated women, Research & Planning (R&P) used available data on nurses, elementary & secondary school teachers, and educated state government employees in Wyoming, as well as a control group. The examination of job exit rates and the average age of exiting employees provides context for the experience of nurses in the state’s labor market and explores why some people stay on the job longer than others.

One of the fundamental issues when studying labor market outcomes is determining how an occupation differs from other similarly situated occupations. This can help determine whether market outcomes are occupation-specific or if they are a function of work setting or demographics. To compare jobs requiring advanced training beyond high school that provide opportunities for educated women, R&P used available data on nurses, elementary & secondary school teachers, and educated state government employees in Wyoming. R&P also compared nurses to a randomly selected control group that had identical age, gender, and prior earnings characteristics (Glover, 2002).

This article examines job exit rates and the average age of exiting employees. These comparisons provide context for the experience of nurses in Wyoming’s labor market. Although differences exist, research can show how similar the experiences of nurses, particularly hospital nurses, are to other selected occupations. This research is a subsection of a larger study produced under contract with the Wyoming Health Care Commission.

Data and MethodologyWyoming Unemployment Insurance wage records were used in this study to identify specific employees and employers. The Wage Records database is the definitive source for empirically establishing a person’s work history in Wyoming, including turnover, tenure, and wage progression. The Wyoming Department of Transportation’s Drivers’ License database was matched to wage records to identify employees’ age and gender.

One of the difficulties in studying occupational outcomes is that wage records do not identify a person’s occupation. Occupations (e.g., nurses and teachers) were identified from the following files: registered nurses from the Nursing Licensure database provided by the Wyoming State Board of Nursing, state employees and their respective job titles from the Wyoming State Auditor’s Office, and teachers from the Wyoming Department of Education’s Education Staff File.

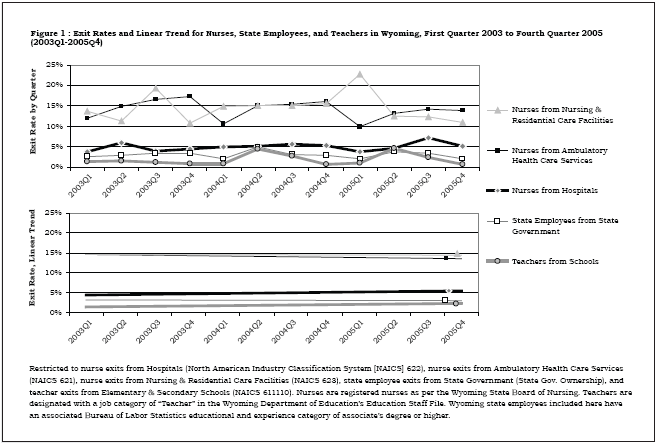

The base year for all three occupational cohorts was 2003. The methodology for calculating turnover was developed previously by Glover (2001). Exit rates were restricted to nurse exits from hospitals, ambulatory health care services, and nursing & residential care facilities; state employee exits from state government; and teacher exits from elementary & secondary schools. Nurses were registered as indicated by the Wyoming State Board of Nursing. Teachers were designated with a job category of “Teacher” in the Wyoming Department of Education’s Education Staff File. Wyoming state employees included here had an associated Bureau of Labor Statistics educational and experience category of associate’s degree or higher for their respective job titles (i.e., they were working in occupations requiring a post-secondary degree).

Statistically matched control groups were constructed using methodology developed by Glover (2002). This was done by stratifying the nurse group by age, gender, and prior wages. Some nurses were eliminated from the file primarily due to a lack of data on prior earnings. A control group of non-nurses was then selected with identical age, gender, and prior wage distributions. Quasi-experimental designs like this allow comparison of groups of persons who are statistically similar at a particular reference point — in this case, nurses with non-nurses.

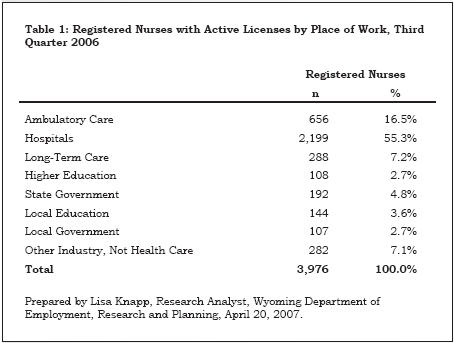

Exit Rate ComparisonsAmong the groupings considered here, hospital nurses, state government employees, and teachers had turnover rates at or below 5% each quarter (see Figure 1). Teaching was the most stable of the three occupations (exiting later in the work career). Nursing appeared to be the least stable among the three occupations. Hospital nurses, however, had turnover rates clustered more closely with teachers and state government employees. Nurses working in ambulatory health care services and nursing & residential care facilities had very similar turnover rates but were approximately 10 percentage points higher than nurses working in hospitals. In third quarter 2003, more than half of Wyoming nurses worked in hospitals (see Table 1).

A study of exit patterns among nurses was presented in “Where Did the Nurse Go? Using Administrative Data to See Changes in Employment in Nursing” in June 2007 Wyoming Labor Force Trends.

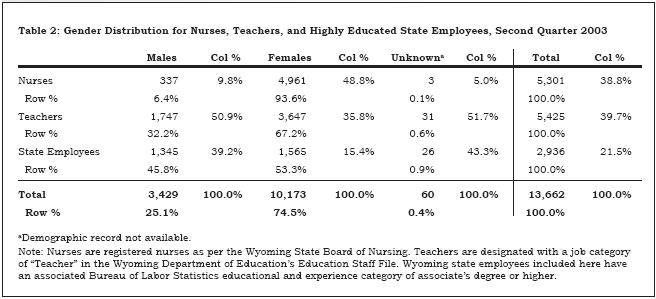

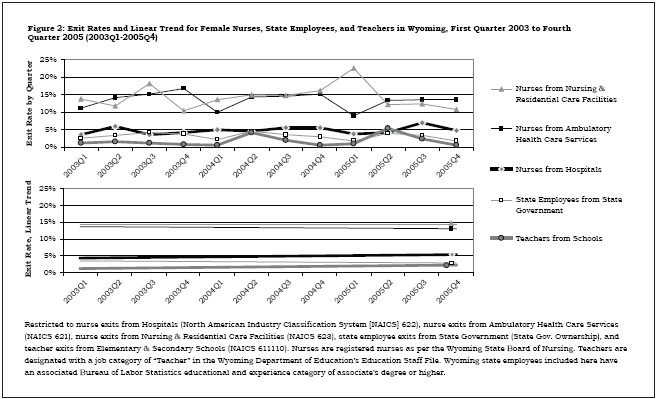

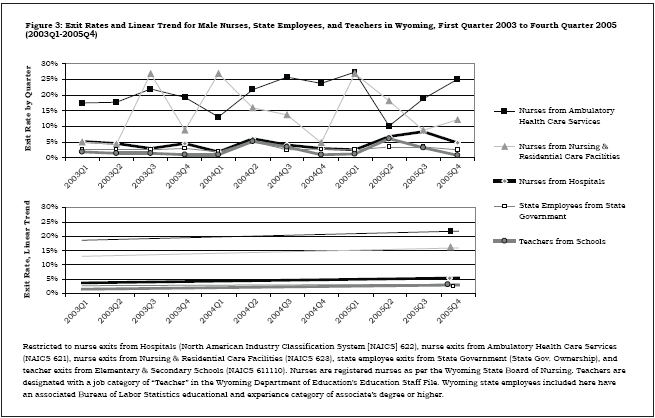

Because nursing has a much higher concentration of female employees than either teaching or state government employment (see Table 2), turnover rates were run separately for males and females. Turnover rates for professional females showed a very similar pattern to the rates for all employees (compare Figure 1 and Figure 2). Rates for males followed the same general pattern but were more erratic for nurses from ambulatory health care services and nursing & residential care facilities (see Figure 3), likely due to the small number working in these settings.

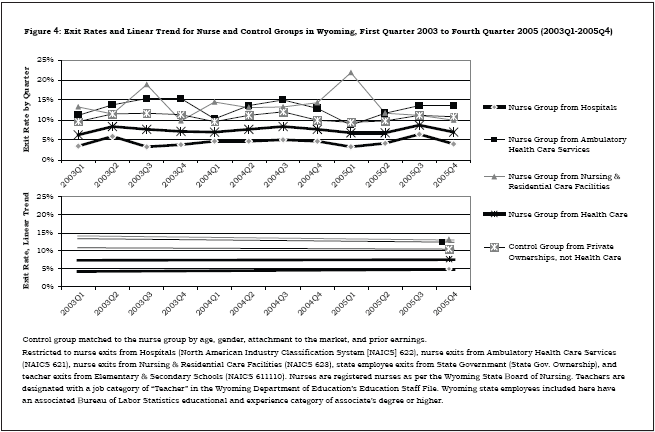

As anticipated when comparing nurse and control groups, nurses from hospitals, nurses from ambulatory health care services, and nurses from nursing & residential care facilities had exit rates similar to those shown previously (see Figure 4). Due to the stratification process, this was a smaller subset of nurses than those examined previously; however, the stratification process did not alter the general pattern of turnover. Members of the control group who exited from private ownerships (not including health care) had approximately a 10% exit rate each quarter, while nurses who exited from health care (all three nurse groups) had approximately a 7% exit rate per quarter. The control group had higher turnover than nurses from hospitals and nurses from health care. However, nurses from ambulatory health care services and nursing & residential care facilities had the highest rates of turnover.

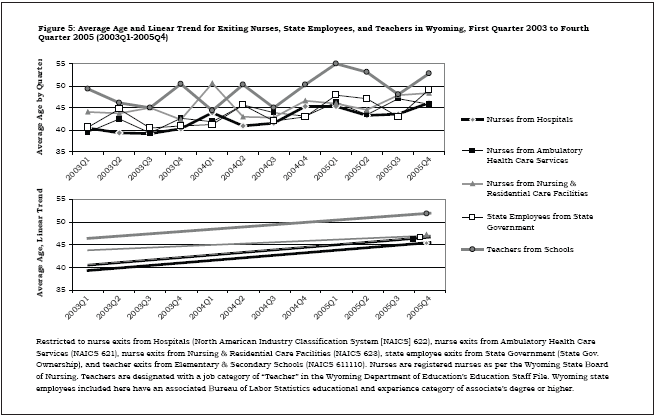

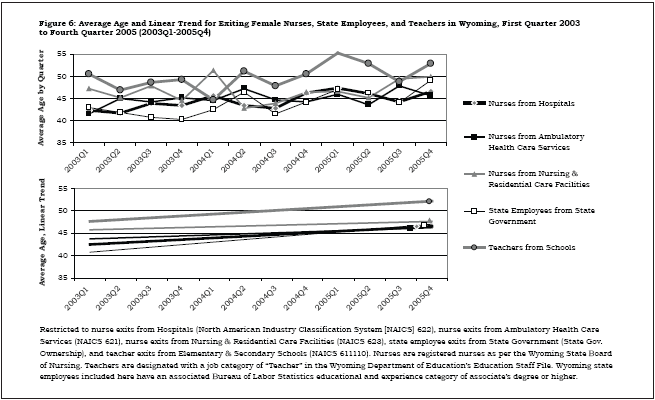

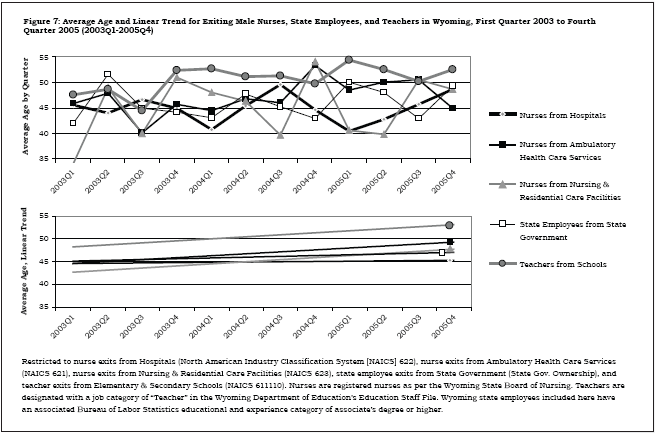

Average Age ComparisonsThe average age of exiters can also be used for comparison. Among the occupational groups considered here, most clustered tightly within a 4-year age range (see Figure 5). The notable exception was teachers within elementary & secondary schools, whose average age was 2 to 3 years older than the other groups, supporting the idea that teaching appears to be a more stable occupation than nursing or state government employment. Comparisons restricted to females were similar to the pattern for all employees (see Figure 6). The pattern for males was also similar but showed more variability, particularly among nurses from health care occupations due to the small number of male nurses (see Figure 7). Average age comparisons were not meaningful between the nurse group and the matched control group due to the fact that they were statistically forced to be identical through the stratification process.

SummaryThis turnover analysis indicates that exit rates for nurses from hospitals were similar to other occupations that concentrate professional females — namely elementary & secondary school teachers and state employees working in occupations that require post-secondary education. Members of the statistically matched control group working in Wyoming’s private sector economy and nurses from ambulatory health care services and nursing & residential care facilities had somewhat higher rates of turnover. Hospitals, similar to teaching and state government employment, may provide more stable avenues of employment. Characteristics of the work setting, rather than occupation, potentially explain exit rates. Future studies will explore explanatory variables, particularly wage differences.

ReferencesGlover, W. (2001). Turnover analysis: Definitions, process, and quantifications. Retrieved August 16, 2007, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/w_r_research/Turnover_Methodology.pdf

Glover, W. (2002). Compared to what? Purpose and method of control group selection. Wyoming Labor Force Trends, 39(6). Retrieved August 17, 2007, from http://doe.state.wy.us/LMI/0602/a2.htm

Return to text

Return to text

Return to text

Return to text

Return to text

Return to text

Return to text

Return to text

Return to text

Last modified on

by April Szuch.